The female pelvis serves as a bony connection between the torso and the lower limbs. It plays a crucial role in supporting the torso and protecting pelvic organs, while also forming the bony birth canal through which the fetus passes during childbirth. The size and shape of the pelvis directly affect labor and delivery. Compared to the male pelvis, the female pelvis is typically wider and shallower, facilitating fetal delivery.

Composition of the Pelvis

Pelvic Bones

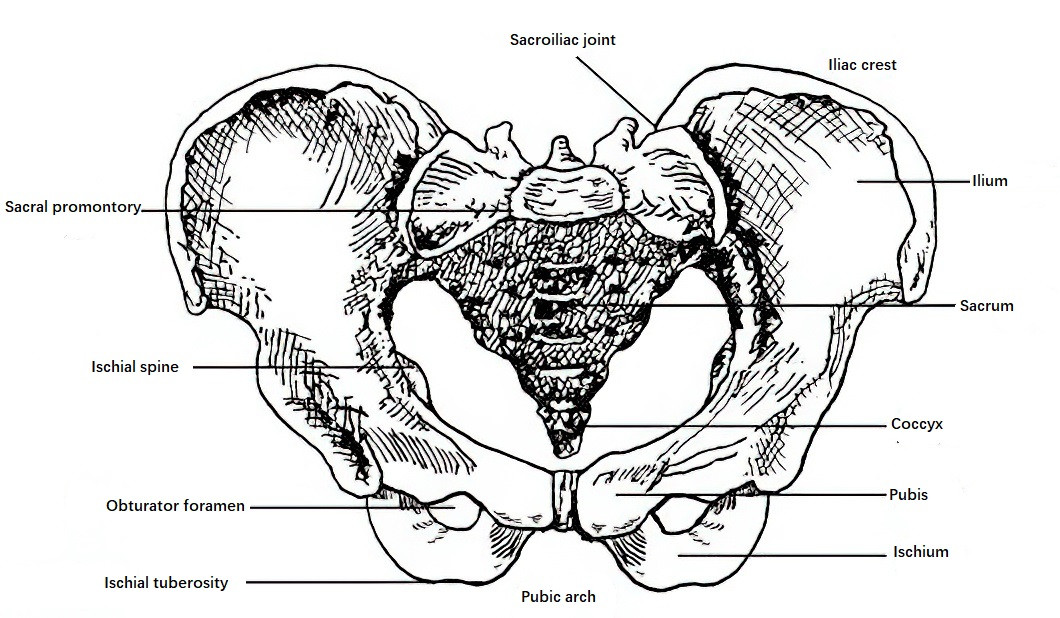

The pelvis consists of the sacrum, coccyx, and two hip bones. Each hip bone is formed by the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. The sacrum is composed of 5–6 fused sacral vertebrae and has a wedge-like (triangular) shape. Its upper margin protrudes prominently forward and is called the sacral promontory, which serves as an important landmark in gynecological laparoscopic surgery and a reference point for diagonal conjugate measurements in obstetrics. The coccyx consists of 4–5 fused coccygeal vertebrae.

Figure 1 Normal female pelvis (Anterior-superior view)

Pelvic Joints

Pelvic joints include the pubic symphysis, sacroiliac joint, and sacrococcygeal joint. The pubic symphysis is a fibrocartilaginous joint connecting the two pubic bones anteriorly. During pregnancy, it becomes more flexible under the influence of sex hormones, and slight separation may occur during delivery to facilitate fetal passage. Posteriorly, the sacroiliac joints connect the ilium to the sacrum. The sacrococcygeal joint connects the sacrum to the coccyx and has limited mobility, which allows the coccyx to move posteriorly during delivery, increasing the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet.

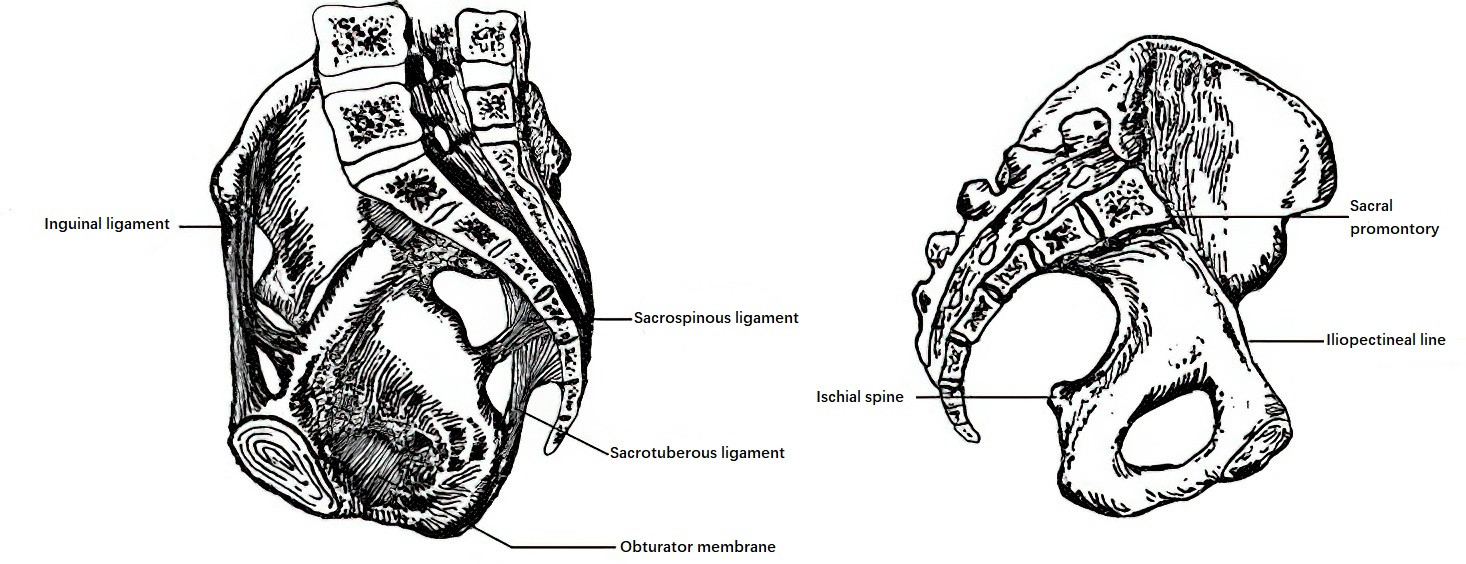

Pelvic Ligaments

Among the ligaments connecting various parts of the pelvis, two pairs are particularly important: the sacrotuberous ligaments between the sacrum and the ischial tuberosities, and the sacrospinous ligaments between the sacrum and the ischial spines. The width of the sacrospinous ligaments determines the width of the sciatic notches, which is a critical indicator for assessing pelvic narrowing in the mid-pelvis. During pregnancy, ligaments are loosened under the influence of sex hormones, enhancing flexibility for delivery.

Figure 2 Ligaments of the pelvis

Pelvic Divisions

A line connecting the upper margin of the pubic symphysis, the iliopectineal lines, and the upper margin of the sacral promontory divides the pelvis into the false pelvis and the true pelvis. The false pelvis, also known as the greater pelvis, lies above this line and is part of the abdominal cavity. It is bounded anteriorly by the lower abdominal wall, laterally by the iliac wings, and posteriorly by the fifth lumbar vertebra. The false pelvis has no direct role in the birth canal. The true pelvis, also known as the lesser pelvis, forms the bony birth canal.

The true pelvis consists of an inlet (pelvic inlet), an outlet (pelvic outlet), and the pelvic cavity in between. The posterior wall of the pelvic cavity is formed by the sacrum and coccyx, the lateral walls by the ischium, ischial spines, and sacrospinous ligaments, and the anterior wall by the pubic symphysis and pubic rami. The ischial spines are located in the midline of the true pelvis and can be palpated during rectal or vaginal examination. The interspinous diameter, measured between the ischial spines, is a key parameter for assessing the transverse diameter of the mid-pelvis and serves as an important reference point during labor to measure the descent of the fetal presenting part. The anterior portion of the pubic rami forms the pubic arch. The pelvic cavity has a shallow anterior wall and a deeper posterior wall, and the central axis of the pelvis forms the pelvic axis, along which the fetus descends during delivery.

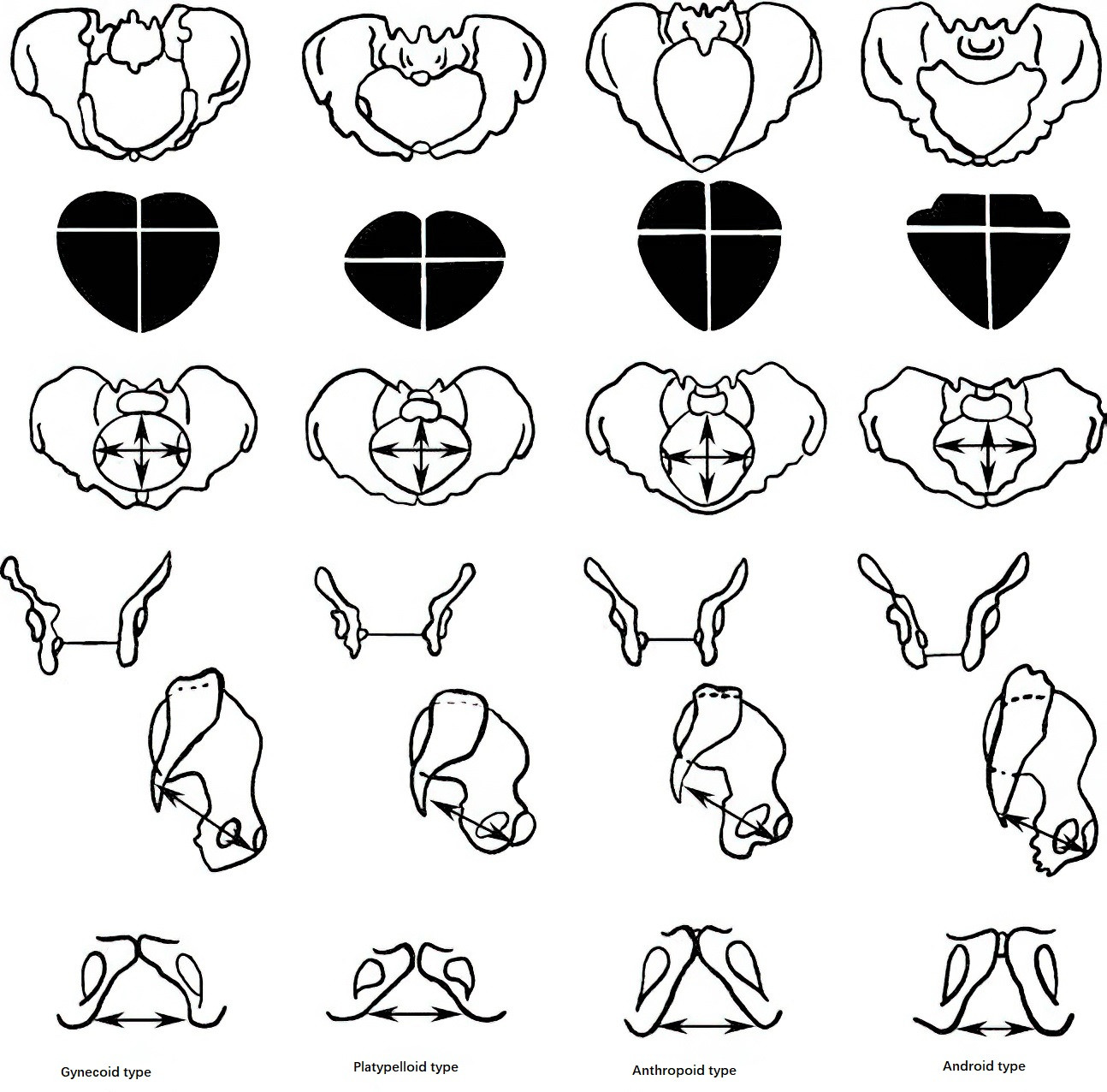

Pelvic Types

Based on pelvic morphology (according to the Caldwell and Moloy classification), the pelvis is categorized into four basic types:

Figure 3 Four basic types of pelvis and their comparative anatomy

Gynecoid Type

The pelvic inlet is transversely oval, with the transverse diameter slightly longer than the anteroposterior diameter. The pubic arch is broad, and the interspinous diameter is ≥10 cm. This is the most common type and represents the normal female pelvis, observed in 52%–58.9% of women.

Platypelloid Type

The pelvic inlet is flat and oval-shaped, with the transverse diameter exceeding the anteroposterior diameter. The pubic arch is wide, and the sacrum lacks its normal curvature, becoming straight or upwardly arched, resulting in a short sacrum and shallow pelvis. This type is relatively common, occurring in 23.2%–29% of

women.

Anthropoid Type

The pelvic inlet is vertically oval, with the anteroposterior diameter longer than the transverse diameter. The pelvic side walls converge slightly, the ischial spines are prominent, and the sciatic notches are wide. The pubic arch is narrow, and the sacrum tilts backward, creating a narrower anterior pelvis and a wider posterior pelvis. The sacrum often consists of six segments, making this pelvis deeper than other types. This type occurs in 14.2%–18% of women.

Android Type

The pelvic inlet is somewhat triangular, with converging side walls and prominent ischial spines. The pubic arch is narrow, and the sciatic notches are narrow and high-arched. The sacrum is relatively straight and tilts forward, reducing the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet. The pelvic cavity is funnel-shaped, often leading to obstructed labor. This type is rare, accounting for only 1%–3.7%.

The above four pelvic types represent theoretical classifications. In clinical practice, mixed pelvic types are more commonly observed. The shape and size of the pelvis vary not only by ethnicity but are also influenced by factors such as genetics, nutrition, and sex hormone levels during growth and development.

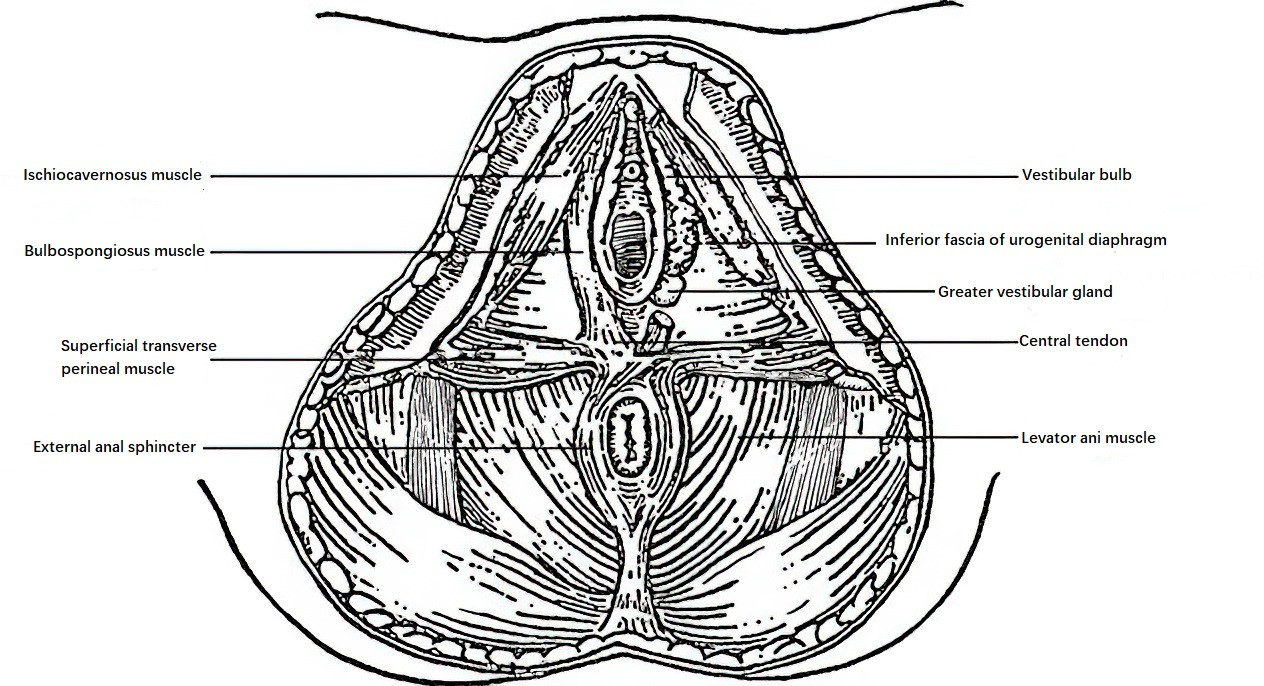

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor consists of multiple layers of muscles and fascia, forming a closure for the pelvic outlet. It supports and maintains the pelvic organs, such as the internal reproductive organs, bladder, and rectum, in their normal positions. Abnormalities in the structure and function of the pelvic floor may result in pelvic organ prolapse, descent, or functional disorders. Various degrees of pelvic floor tissue damage or functional impairment can occur during childbirth.

Figure 4 Pelvic floor

The pelvic floor is bound anteriorly by the pubic symphysis and the pubic arch, posteriorly by the tip of the coccyx, and laterally by the inferior pubic rami, ischial rami, and ischial tuberosities. A line connecting the anterior edges of the ischial tuberosities divides the pelvic floor into two triangular regions. The anterior triangle, called the urogenital triangle, slopes downward and backward, and is traversed by the urethra and vagina. The posterior triangle, called the anal triangle, slopes downward and forward, and is traversed by the anal canal. From the outside inward, the pelvic floor is composed of three layers.

Outer Layer

The outer layer, located underneath the external genitalia, perineal skin, and subcutaneous tissue, consists of superficial perineal fascia and three pairs of muscles along with a sphincter muscle. The tendons of these muscles converge between the vaginal introitus and the anus to form the perineal body (central tendon).

- Bulbospongiosus Muscle: Covers the vestibular bulbs and the greater vestibular glands, extending anteriorly along both sides of the vagina to insert into the root of the clitoral corpus cavernosum. Posteriorly, it intersects with the external anal sphincter. Contraction of this muscle can constrict the vaginal opening, and for this reason, it is also referred to as the vaginal sphincter.

- Ischiocavernosus Muscle: Originates from the inner aspect of the ischial tuberosity, extending along the ischial ramus and inferior pubic ramus to insert into the clitoral corpus cavernosum at the clitoral crura.

- Superficial Transverse Perineal Muscle: Extends from the inner aspect of both ischial tuberosities to converge at the perineal body.

- External Anal Sphincter: Consists of circular muscle fibers surrounding the anus, with the anterior portion converging into the perineal body.

Middle Layer

The middle layer constitutes the urogenital diaphragm, which includes superior and inferior layers of dense fascia and contains the deep transverse perineal muscles and the urethral sphincter. This layer covers the triangular area of the anterior pelvic outlet and is also referred to as the triangular ligament, through which the urethra and vagina pass.

- Deep Transverse Perineal Muscle: Extends from the inner surface of the ischial tuberosities to the central tendon, lying deep to the superficial transverse perineal muscle.

- Urethral Sphincter: Surrounds the urethra and regulates urination.

Inner Layer

The innermost layer is the pelvic diaphragm, which is the most robust layer of the pelvic floor. It consists of the levator ani muscles and their associated fascia. The urethra, vagina, and rectum pass through this layer from anterior to posterior.

The levator ani muscle is a paired, flattened muscle located in the pelvic floor and forms a funnel shape as it slopes inward and downward. This muscle constitutes the majority of the pelvic floor and is composed of three parts on each side:

- Pubococcygeus Muscle: The primary component of the levator ani muscle. Its fibers originate from the medial aspect of the inferior pubic ramus, loop around the vagina and rectum, and attach posteriorly to the coccyx. A small portion of the muscle fibers insert around the vagina and rectum. The pubococcygeus muscle is susceptible to damage during childbirth, which may result in pelvic organ prolapse (such as cystocele or rectocele).

- Iliococcygeus Muscle: Originates from the posterior part of the tendinous arch (a thickened portion of the obturator internus fascia), blending with the pubococcygeus muscle and encircling both sides of the anus before attaching to the coccyx.

- Coccygeus Muscle: Originates from the ischial spines and inserts into the sacrum and coccyx.

Among the pelvic floor muscles, the levator ani muscle plays the most important role in pelvic support. The interwoven muscle fibers around the vagina and rectum contribute to strengthening the anal and vaginal sphincters.

The pelvic cavity can be divided into anterior, middle, and posterior sections along the vertical axis. When the supporting function of the pelvic floor is compromised, corresponding pelvic organs are prone to relaxation, prolapse, or functional defects. In the anterior region, bladder and anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele) may occur. In the middle section, uterine or vaginal vault prolapse may develop. In the posterior section, rectal and posterior vaginal wall prolapse (rectocele) may arise.

The term "perineum" has both broad and narrow definitions. Broadly, it refers to all the soft tissues enclosing the pelvic outlet, extending from the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis anteriorly to the tip of the coccyx posteriorly, laterally bounded by the inferior pubic rami, ischial rami, ischial tuberosities, and sacrotuberous ligaments. Narrowly, the perineum refers to the wedge-shaped soft tissue located between the vaginal introitus and the anus, which measures about 3–4 cm in thickness and is also known as the perineal body. The perineal body consists of skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, portions of the levator ani muscle, and the central tendon. The central tendon is formed by interwoven fibers from the levator ani muscle, its associated fascia, the superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles, the bulbospongiosus muscle, and the external anal sphincter.

The perineum has considerable elasticity, and its tissues soften during late pregnancy to facilitate delivery. Protecting the perineum during childbirth is critical to avoid tears.