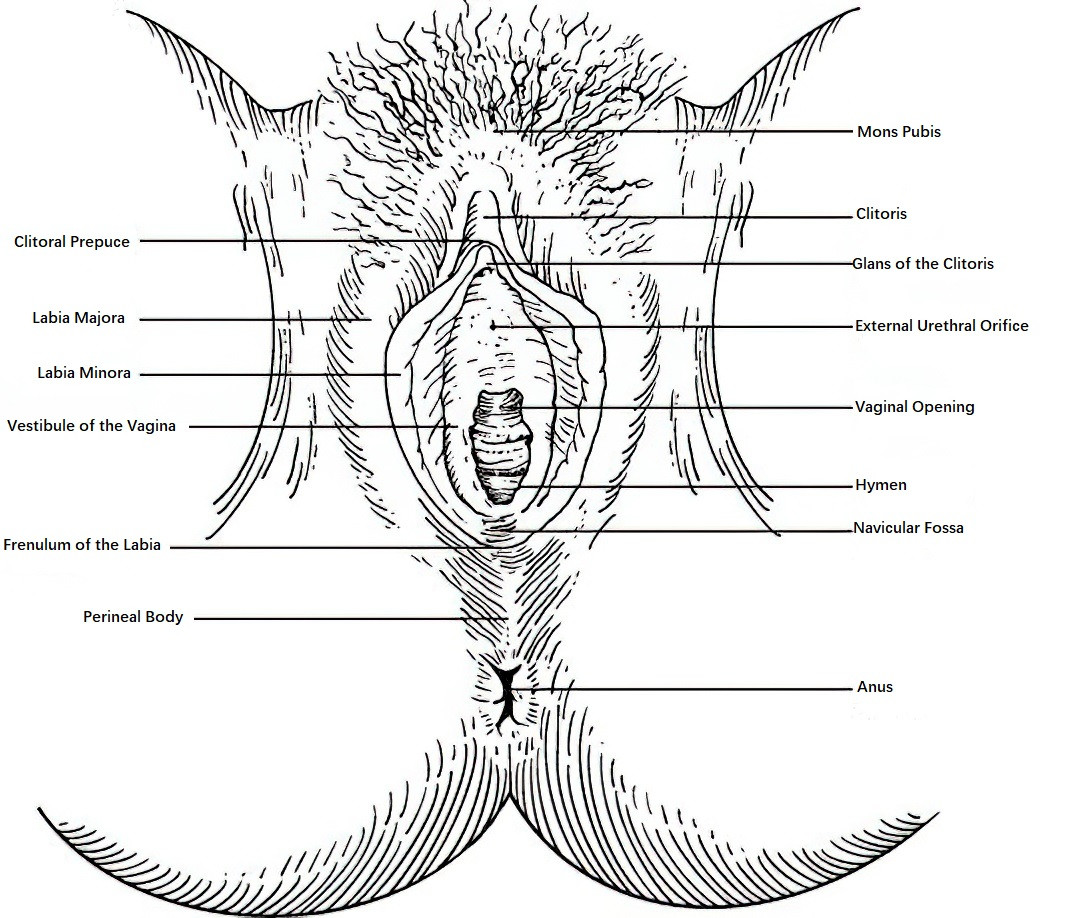

External Genitalia

The female external genitalia, also known as the vulva, include the visible parts of the reproductive system. Located between the inner sides of the thighs, the external genitalia extend from the pubic symphysis anteriorly to the perineal body posteriorly. The vulva consists of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and the vaginal vestibule.

Figure 1 External female genitalia

Mons Pubis

The mons pubis is a fatty prominence situated anterior to the pubic symphysis. During puberty, the overlying skin develops pubic hair, typically distributed in an inverted triangular pattern, which is considered a secondary sexual characteristic in females. The density and coloration of pubic hair vary among races and individuals.

Labia Majora

The labia majora are a pair of longitudinal skin folds located on the inner sides of the thighs, extending from the mons pubis downward and posteriorly to the perineum. The outer surface is covered in skin, which develops pigmentation and pubic hair after puberty, and contains sebaceous and sweat glands. The inner surface, resembling mucosa, is moist. Beneath the skin lies loose connective tissue and adipose tissue, rich in blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves. Due to this structure, the labia majora are prone to hematoma formation and severe pain in the event of trauma. In nulliparous women, both sides of the labia majora naturally close together, while in parous women, they separate, and in postmenopausal women, they gradually atrophy.

Labia Minora

The labia minora are a pair of thin skin folds located medial to the labia majora. Their surface is moist, brownish, hairless, and covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Their internal structure includes papillary projections, which are rich in nerve endings, making them highly sensitive. The size and shape of the labia minora vary considerably among individuals. Anteriorly, the labia minora fuse and then split into anterior and posterior segments. The anterior segments form the clitoral hood (prepuce), while the posterior segments form the frenulum of the clitoris. The posterior ends of the labia minora meet at the midline to form the frenulum of the pudendal labia.

Clitoris

The clitoris is located beneath the anterior ends of the labia minora and is homologous to the male penis. It is composed of erectile tissue, making it capable of engorgement. The clitoris is divided into three parts:

- The glans clitoris, positioned at the anterior portion and exposed to the external genitalia, is composed of spindle-shaped cells and rich in nerve endings, making it highly sensitive to sexual stimulation.

- The clitoral body, located in the middle.

- The crura of the clitoris, which attach to the inferior pubic ramus and ischial ramus on either side.

Vaginal Vestibule

The vaginal vestibule is a rhomboid-shaped area bordered by the clitoris anteriorly, the frenulum of the pudendal labia posteriorly, and the labia minora laterally. A shallow depression, known as the navicular fossa (fossa navicularis) or vestibular fossa, is located between the vaginal orifice and the frenulum of the pudendal labia. This fossa may disappear in women who have delivered vaginally. Within the vestibule, several key structures are present:

Vestibular Bulbs

Also known as the bulbospongiosus, the vestibular bulbs are located on either side of the vaginal vestibule. These are composed of erectile venous plexuses. The anterior end of each bulb connects to the clitoris, while the posterior end enlarges and lies adjacent to the corresponding greater vestibular gland. The bulbs are covered by the bulbospongiosus muscle.

Greater Vestibular Glands

Also referred to as Bartholin glands, the greater vestibular glands are located at the posterior parts of the labia majora and are covered by the bulbospongiosus muscle. They are roughly the size of a soybean, with one gland situated on each side. The glands have slender ducts (1–2 cm long) that open medially into the groove between the labia minora and the hymen at the posterior part of the vaginal vestibule. During sexual arousal, these glands secrete mucus, which serves as a lubricant. Under normal circumstances, the glands are not palpable. However, if the duct becomes obstructed, a vestibular gland cyst may form, becoming palpable and visible. In cases of infection, an abscess may develop, causing swelling and discomfort.

External Orifice of the Urethra

The external urethral orifice is located inferoposterior to the glans clitoris. It has a circular shape with folded edges. On the posterior wall of the urethral orifice, there are a pair of small glands known as paraurethral glands. These glands have small openings that are susceptible to bacterial colonization. If infection occurs, an abscess may form, compressing the urethra and causing difficulty with urination.

Vaginal Orifice and Hymen

The vaginal orifice is located in the posterior part of the vestibule, inferior to the urethral orifice. Its margins are encircled by a thin mucosal fold known as the hymen. The hymen contains connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerve endings. Typically, the hymen has a central opening that may be round or crescent-shaped, though occasionally it may be sieve-like or umbrella-shaped. The size of the hymenal opening varies significantly, ranging from being so small that it cannot admit a fingertip, to being large enough to accommodate two fingers, or even being absent altogether. The hymen may be torn during sexual intercourse or other forms of trauma. Vaginal delivery also affects the hymen, leaving only remnants known as hymenal caruncles.

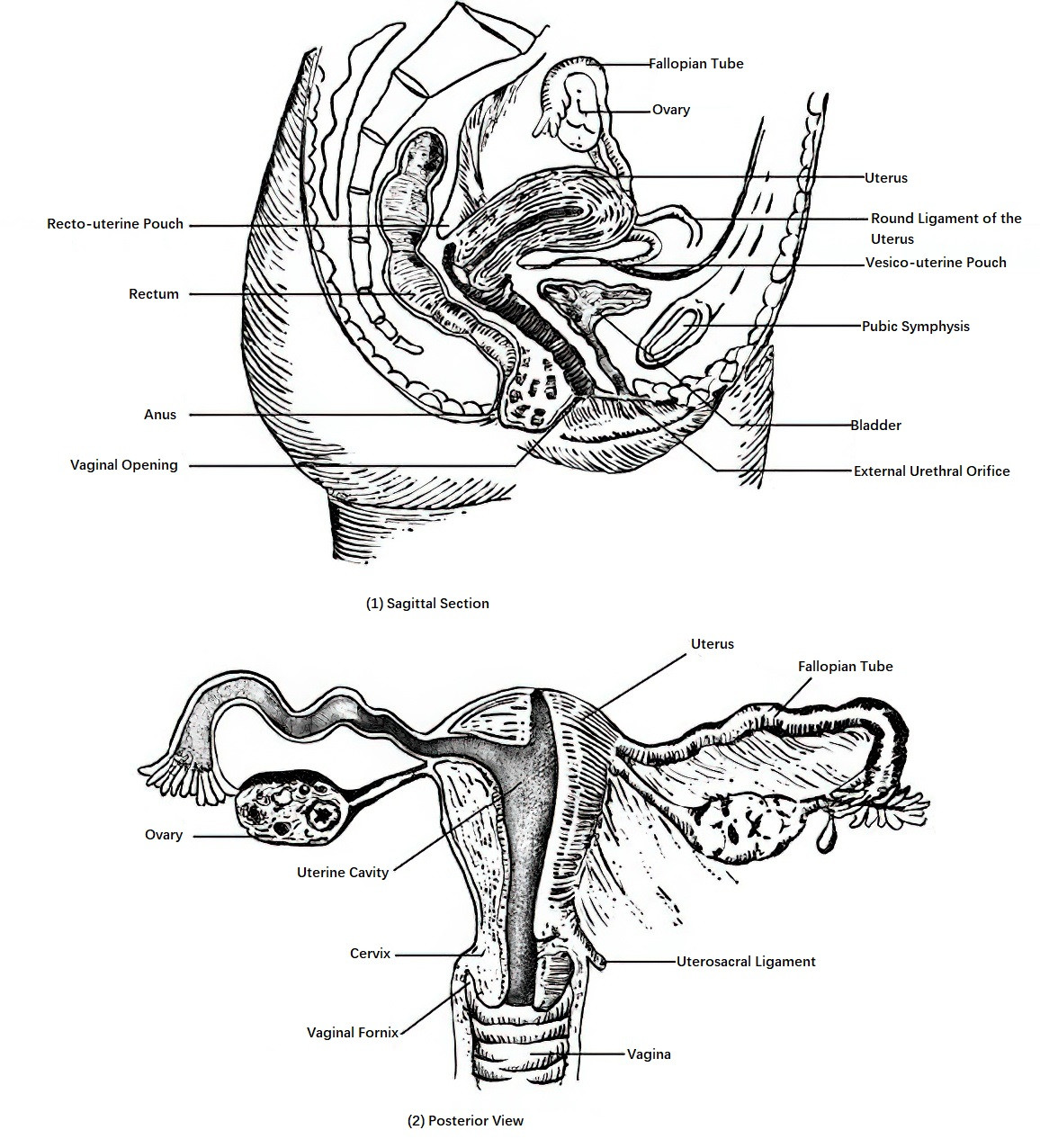

Internal Genitalia

The female internal genitalia are located within the true pelvis and include the vagina, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The latter two are collectively referred to as the uterine adnexa.

Figure 2 Internal female genitalia

Vagina

The vagina serves as the organ for sexual intercourse, the pathway for menstrual blood, and the birth canal for fetal delivery.

Position and Shape

The vagina is situated centrally in the lower part of the true pelvis. It is a tube that widens at the top and narrows toward the bottom. The anterior vaginal wall measures 7–9 cm in length and is adjacent to the bladder and urethra, while the posterior vaginal wall measures 10–12 cm in length and is closely related to the rectum. The vagina consists of anterior, posterior, and two lateral walls, with the anterior and posterior walls typically lying in apposition. Its upper end surrounds the vaginal portion of the cervix, and the lower end opens into the posterior part of the vaginal vestibule. Around the circumference of the vaginal portion of the cervix, a recess called the vaginal fornix is formed. The vaginal fornix is divided into anterior, posterior, left, and right parts based on its position. The posterior fornix is the deepest and lies in close proximity to the rectouterine pouch, which is the lowest point of the pelvic cavity. Clinically, the posterior fornix can be used for procedures such as percutaneous puncture, drainage, or surgical access.

Tissue Structure

The vaginal wall is composed of three layers from the inside out: mucosa, muscle layer, and fibrous tissue membrane. The mucosal layer is formed by non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which lacks glands. It has a pale reddish color and contains numerous transverse folds, providing the vagina with a high degree of elasticity. The vaginal mucosa undergoes cyclical changes under the influence of sex hormones. The muscle layer consists of an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle. The fibrous tissue membrane closely adheres to the muscle layer. The vaginal wall is rich in venous plexuses, making it prone to bleeding or hematoma formation in cases of trauma. After menopause, the vaginal mucosa becomes thinner, the folds diminish, elasticity decreases, and local resistance is reduced, making the area more susceptible to infection.

Uterus

The uterus functions as the organ for embryonic and fetal development as well as the source of menstrual flow. Its shape, size, position, and structure vary with age and undergo changes due to the menstrual cycle and pregnancy.

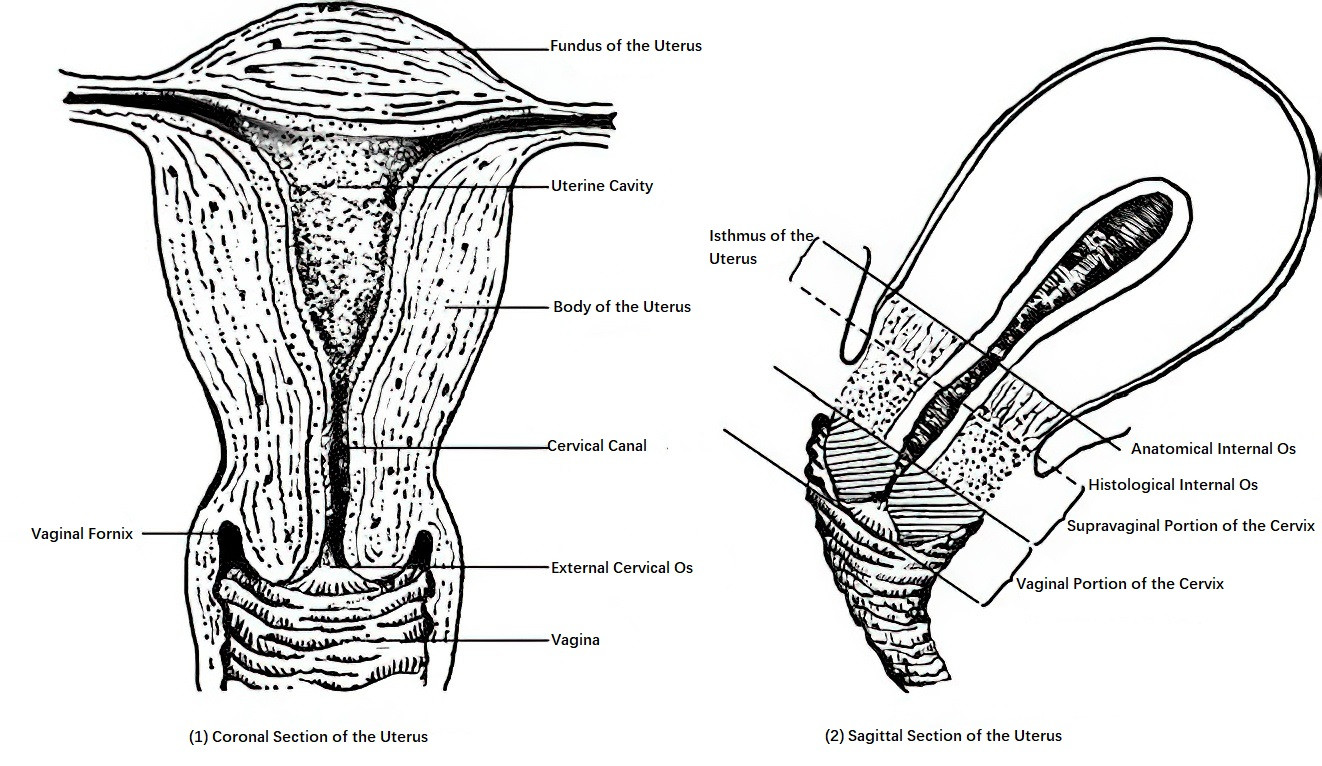

Figure 3 Parts of the uterus

Shape

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ with thick walls, shaped like an inverted pear that is slightly flattened anteroposteriorly. It weighs approximately 50–70 g and measures about 7–8 cm in length, 4–5 cm in width, 2–3 cm in thickness, with a cavity capacity of approximately 5 ml. The uterus is divided into two parts: the uterine body (corpus uteri) and the cervix (cervix uteri).

The uterine body, which is wider, is located in the upper part of the uterus. Its topmost region is referred to as the fundus (fundus uteri), and the areas on either side of the fundus are known as the uterine cornua (cornua uteri). The cervix is narrower, cylindrical in shape, and is located at the lower part of the uterus. The ratio of the uterine body to the cervix varies with age and ovarian function: 1:2 before puberty, 2:1 during the reproductive years, and 1:1 after menopause.

The uterine cavity is triangular in shape, wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, with its upper corners connected to the fallopian tubes, while its lower tip leads to the cervical canal. The narrowest part between the uterine body and the cervix is called the uterine isthmus (isthmus uteri), which measures about 1 cm in length when the uterus is not pregnant. The upper part of the isthmus, known as the anatomical internal os, is anatomically narrow, whereas its lower part, called the histological internal os, marks the transition of the endometrium to cervical mucosa. During pregnancy, the isthmus gradually stretches and lengthens, reaching 7–10 cm by late pregnancy to form the lower uterine segment. This segment becomes part of the soft birth canal and serves as a common site for cesarean section incisions.

The cervical canal, a spindle-shaped cavity within the cervix, typically measures 2.5–3.0 cm in length in adult women. The lower end of the canal opens into the vagina and is referred to as the external os (external cervical os). The cervix is divided into upper and lower parts by the vaginal fornix. The upper two-thirds, known as the supravaginal part of the cervix, is connected to the cardinal ligaments on both sides. The lower third, referred to as the vaginal portion of the cervix, extends into the vagina. In nulliparous women, the external os appears as a circular opening, whereas in multiparous women, it often transforms into a transverse slit due to vaginal deliveries, forming anterior and posterior cervical lips.

Tissue Structure

The tissue structure differs between the uterine body and the cervix.

Uterine Body

The wall of the uterine body consists of three layers: the endometrium (innermost layer), the myometrium (middle layer), and the serous layer (outermost layer).

Endometrium

The endometrium lines the uterine cavity and lacks a subendometrial layer. It is divided into three layers: the compact layer, the spongy layer, and the basal layer. The upper two-thirds of the endometrium, composed of the compact and spongy layers, is collectively known as the functional layer. This layer undergoes cyclical changes and is shed under the influence of ovarian hormones. The basal layer, which accounts for the lower one-third of the endometrium, lies adjacent to the myometrium and does not undergo cyclical changes.

Myometrium

The myometrium is the thickest layer of the uterine wall, measuring about 0.8 cm in thickness in the non-pregnant state. It consists mainly of smooth muscle tissue, with small amounts of elastic and collagen fibers, and is organized into three layers. The innermost layer contains circularly arranged muscle fibers, which contract spasmodically to form the uterine contraction ring. The middle layer, with interwoven muscle fibers, surrounds blood vessels in a figure 8 configuration, compressing the vessels during contraction to effectively prevent uterine bleeding. The outermost layer contains longitudinally arranged muscle fibers, which are extremely thin and serve as the starting point for uterine contractions.

Serous Layer

This layer corresponds to the peritoneum, covering the fundus and the anterior and posterior surfaces of the uterus. On the anterior surface, the peritoneum reflects at the level of the uterine isthmus to cover the bladder, forming the vesicouterine pouch. On the posterior surface, the peritoneum descends along the uterine wall and reflects at the posterior side of the cervix onto the rectum, forming the rectouterine pouch, also known as the pouch of Douglas.

Cervix

The cervix is primarily composed of connective tissue, with small amounts of smooth muscle, blood vessels, and elastic fibers. The cervical canal is lined by a single layer of columnar epithelium, with glands that secrete alkaline mucus to form a mucous plug that blocks the canal. The composition and consistency of the mucous plug undergo cyclical changes regulated by sex hormones. The vaginal portion of the cervix is covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which gives it a smooth surface. The transitional zone between the columnar epithelium of the external os and the squamous epithelium is a common site for cervical cancer development.

Position

The uterus is centrally located in the pelvic cavity. Anterior to it is the bladder, posterior to it is the rectum, inferiorly it connects to the vagina, and laterally it communicates with the fallopian tubes and ovaries. The uterine fundus lies below the plane of the pelvic inlet, while the external os is slightly above the level of the ischial spines. In adult women with an empty bladder, the uterus is usually in an anteverted and anteflexed position. The normal position of the uterus is maintained by its ligaments as well as the pelvic floor muscles and fascia. Any factors leading to dysfunction or damage of the pelvic floor structures may result in uterine prolapse.

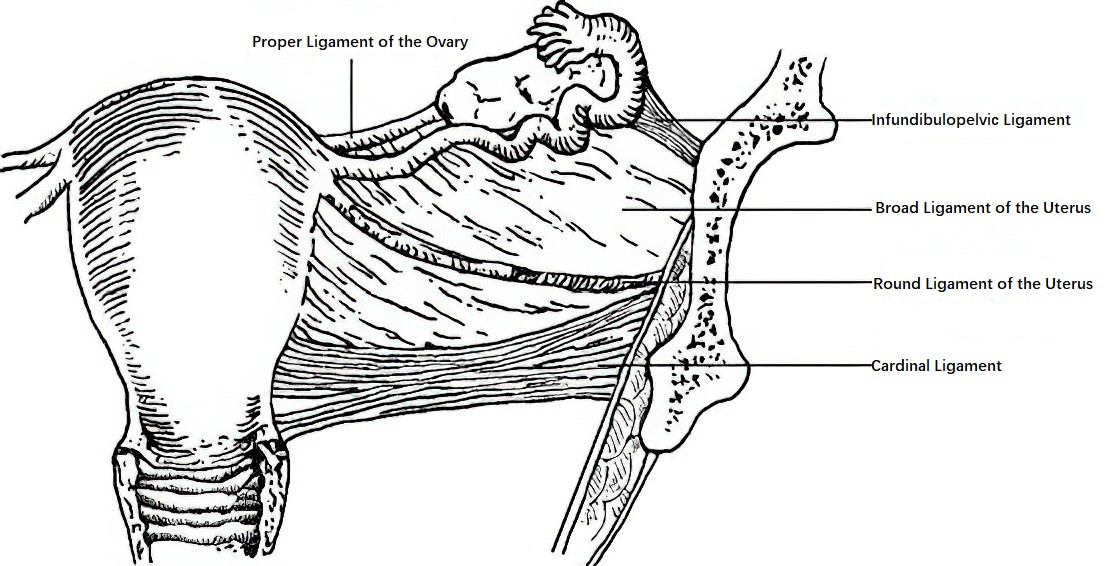

Uterine Ligaments

There are four pairs of uterine ligaments:

Figure 4 Uterine ligaments (Anterior view)

Broad Ligaments of the Uterus

These are wing-like double-layered folds of peritoneum extending bilaterally from the lateral margins of the uterus to the pelvic walls. These ligaments limit lateral displacement of the uterus. The upper free edge of the broad ligament encases the fallopian tubes (excluding the fimbriae). The outer third of this edge surrounds the ovarian blood vessels, forming the infundibulopelvic ligament (or suspensory ligament of the ovary). The medial edge between the uterine cornua and the ovary contains the ovarian ligament. Differentiated portions of the broad ligament include the mesosalpinx, mesovarium, and paracervical tissue, which include extensive vascular, neural, and lymphatic networks as well as loose connective tissue.

Round Ligaments of the Uterus

These cylindrical structures are composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue and measure 12–14 cm in length. They originate anteriorly from the uterine cornua near the proximal fallopian tubes and pass through the inguinal canals to terminate at the labia majora. The round ligaments play a role in maintaining the anteverted position of the uterus.

Cardinal Ligaments of the Uterus

These ligaments are located in the lower portion of the broad ligament, extending transversely from the cervix to the pelvic sidewalls. They are crucial in stabilizing the cervix and preventing uterine prolapse.

Uterosacral Ligaments

These short, thick, and strong ligaments originate posteriorly from the junction of the uterine body and the cervix, running laterally around the rectum to the anterior fascia of the second and third sacral vertebrae. In addition to connective tissue and smooth muscle, these ligaments contain nerves supplying the bladder. Uterosacral ligaments, along with the round ligaments, help maintain the uterus in its normal anteverted and anteflexed position.

Fallopian Tube (Oviduct)

The fallopian tubes are a pair of slender, curved muscular ducts that serve as the site for fertilization and the pathway for transporting fertilized eggs. They are situated along the upper edge of the broad ligament and connect medially to the uterine cornua, with their lateral ends free and fringed, lying in proximity to the ovaries. Each tube measures 8–14 cm in length. Based on its structure, the fallopian tube is divided into four segments, from medial to lateral:

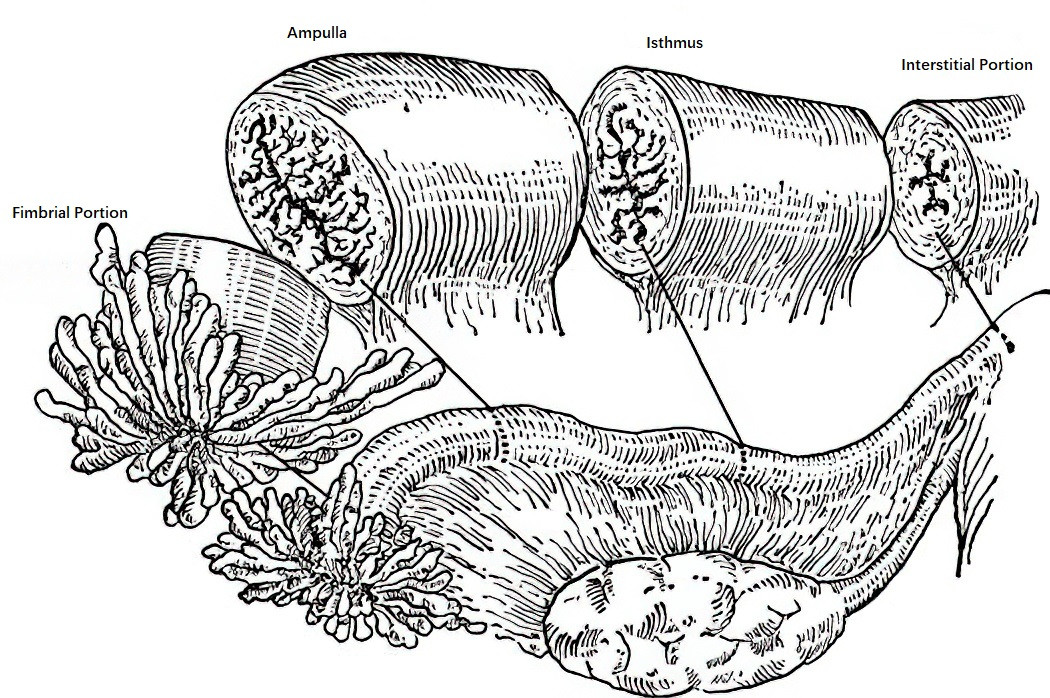

Figure 5 Parts of the fallopian tube and their transverse sections

Interstitial Portion

This segment is embedded within the uterine wall, measuring about 1 cm in length, and has the narrowest lumen.

Isthmic Portion

Located lateral to the interstitial portion, this segment is narrow and relatively straight, with a lumen that is slightly wider than the interstitial portion. It measures 2–3 cm in length, has relatively poor blood supply, and is the most common site for tubal ligation.

Ampulla Portion

Situated lateral to the isthmus, this segment has thin walls and a wider, convoluted lumen. It measures 5–8 cm in length and contains numerous folds. Fertilization typically occurs in this portion.

Fimbrial Portion

This is the outermost segment of the fallopian tube, measuring 1–1.5 cm in length. It opens into the peritoneal cavity and is equipped with numerous finger-like projections (fimbriae) that help capture ovulated eggs.

The wall of the fallopian tube consists of three layers:

- Outer Layer (Serosal Layer): This layer is derived from the peritoneum.

- Middle Layer (Smooth Muscle Layer): The contraction of this layer assists in capturing eggs, transporting fertilized eggs, and to some extent preventing retrograde menstrual flow and the spread of uterine cavity infections to the abdominal cavity.

- Inner Layer (Mucosal Layer): The mucosa is lined with a single layer of tall columnar epithelium, which consists of four types of cells: ciliated cells, non-ciliated cells, wedge cells, and undifferentiated cells. The cilia of ciliated cells beat to assist in the transport of fertilized eggs. Non-ciliated cells, also known as secretory cells, secrete mucus. Wedge cells may be precursors of non-ciliated cells, while undifferentiated cells, also known as reserve cells, serve as progenitor cells for the epithelium. Hormonal influences cause cyclical changes in muscle contraction and the morphology, secretory activity, and ciliation of the epithelial cells in the fallopian tubes.

Ovary

The ovaries are paired, oval-shaped gonads that produce and release eggs and secrete steroid hormones. They are suspended between the pelvic wall and the uterus by the infundibulopelvic ligaments (suspensory ligaments of the ovary) laterally and the ovarian ligaments medially. They are connected to the broad ligament via the mesovarium. The anterior border of the ovary contains the hilum, through which nerves and blood vessels enter and exit, traveling through the infundibulopelvic ligament and mesovarium. The posterior border of the ovary is free.

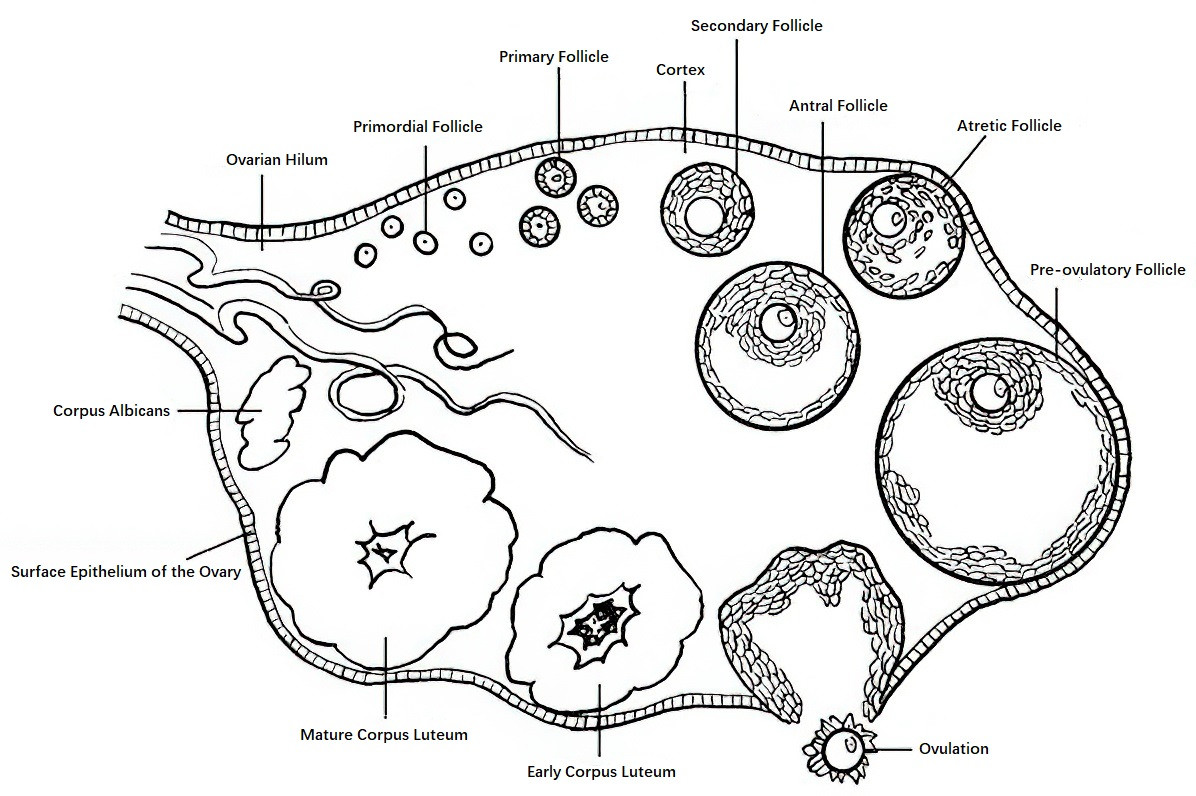

Figure 6 Diagram of the structure of the ovary

The size and shape of the ovaries vary with age. Before puberty, the ovarian surface is smooth. After puberty, during which ovulation begins, the surface gradually becomes irregular. In women of reproductive age, the ovaries measure approximately 4 cm × 3 cm × 1 cm, weigh about 5–6 g, and are grayish-white in color. After menopause, the ovaries gradually shrink, become firm, and are often difficult to palpate during gynecological examinations.

The surface of the ovary is covered by a layer of mesothelium derived from the peritoneum, termed the ovarian surface epithelium. Beneath this epithelium lies a dense layer of connective tissue called the tunica albuginea. Deeper within lies the ovarian parenchyma, which is divided into an outer cortex and an inner medulla.

Cortex

The cortex constitutes the main body of the ovary and contains connective tissue, fibrous tissue, various stages of developing follicles, corpora lutea, and their regressive remnants, as well as stromal tissue. The thickness of the cortex decreases with age.

Medulla

The medullary region is connected to the ovarian hilum and is composed of loose connective tissue, abundant blood vessels, nerves, lymphatic vessels, and a small amount of smooth muscle fibers continuous with the ovarian ligament.