Structural and Functional Characteristics of the Respiratory System

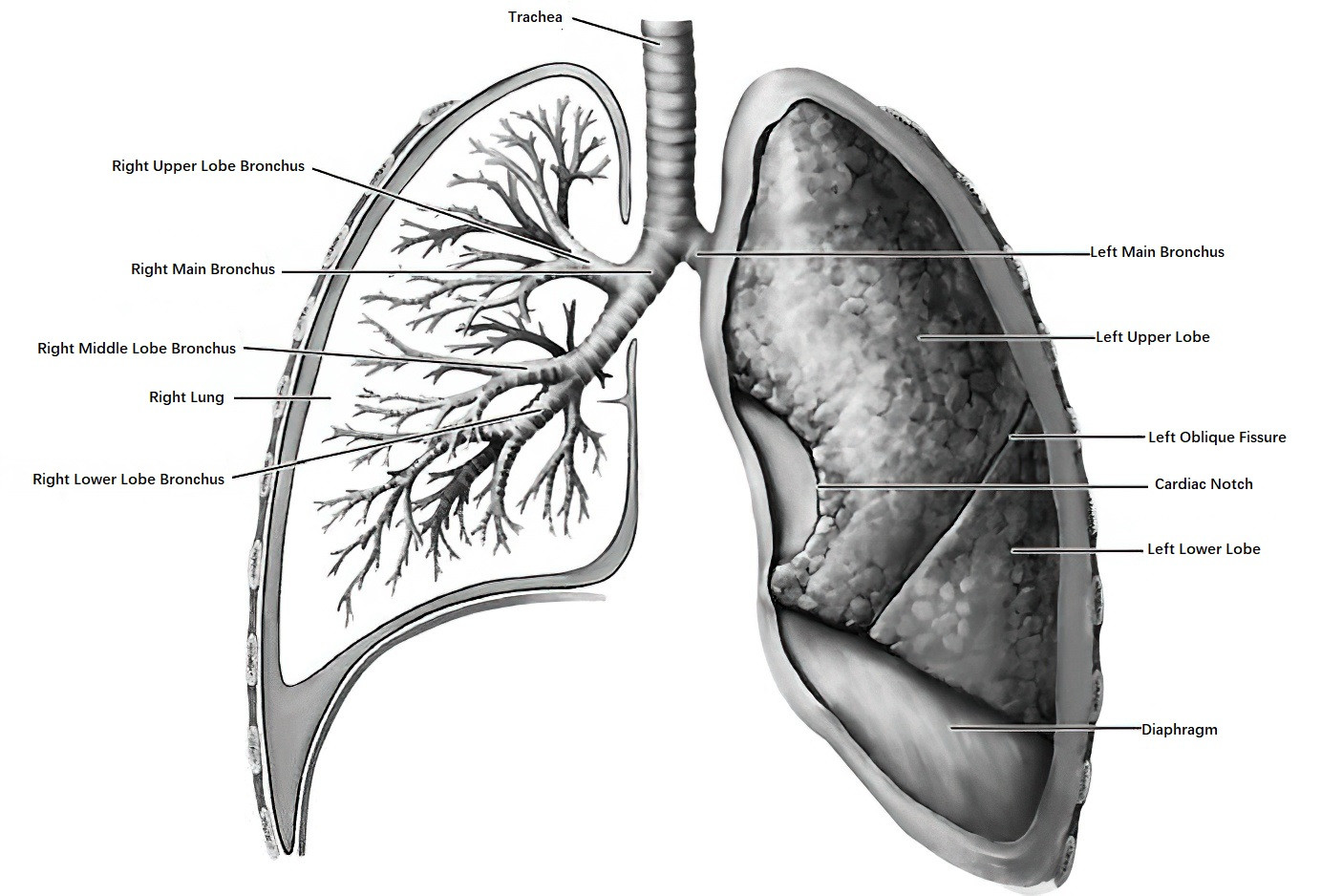

Inhaled air passes through a multilevel branching airway structure to enter the alveoli. After the trachea enters the thoracic cavity, it divides into the left and right main bronchi. The right main bronchus branches into the right upper lobe bronchus and the intermediate bronchus, which further divides into the right middle and right lower lobe bronchi. The left main bronchus branches into the left upper and left lower lobe bronchi, with the upper lobe bronchus further dividing into the segmental bronchus for the upper lobe proper and the lingular segmental bronchus.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the structure of the trachea, bronchi, and lungs

Thus, the right lung is divided into three lobes—upper, middle, and lower—while the left lung is divided into two lobes—upper and lower. These bronchi further subdivide into segmental and subsegmental bronchi, bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, alveolar sacs, and alveoli.

Gas Exchange Function

The respiratory system is in direct communication with the external environment, with the lungs providing an extensive surface area for respiration. In healthy adults, the total respiratory surface area exceeds 100 square meters. Under resting conditions, approximately 10,000 liters of air move in and out of the respiratory tract daily. Oxygen is inhaled through the airway and undergoes gas exchange within the lungs, where carbon dioxide is expelled through the respiratory tract. Gas exchange represents the primary function of the lungs.

Defense Function

During respiration, various organic or inorganic particles from the external environment—such as microorganisms, allergens, particulate matter (PM2.5), harmful gases, and tobacco smoke—can enter the respiratory tract and lungs, potentially causing diseases. The phrase "All veins converge to the lung" highlights the role of the pulmonary circulation as the convergence point for systemic venous blood, making the lungs susceptible to systemic diseases and metabolic toxins. Due to its structural and functional characteristics, the respiratory system is particularly vulnerable to external and internal factors. Consequently, its defense function is crucial. This includes:

- Physical defense mechanisms, such as nasal warming and filtration, sneezing, coughing, bronchoconstriction, and the mucociliary clearance system.

- Chemical defense mechanisms, including lysozymes, lactoferrin, protease inhibitors, antioxidant agents like glutathione and superoxide dismutase.

- Innate immunity, involving alveolar macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils.

- Adaptive immunity, involving B cells that secrete immunoglobulins (IgA, IgM, etc.) and T cell-mediated immune responses.

Diminished defense function due to various causes, or excessive external stimulation, can lead to respiratory system damage or diseases.

Metabolic Function

The lungs exhibit metabolic functions related to biologically active substances, lipids, proteins, and reactive oxygen species.

Circulatory Regulation

The lungs are supplied by both the pulmonary and systemic circulations. The pulmonary artery originates from the right ventricle and branches out to form a capillary network surrounding the alveoli, providing a large surface area conducive to gas exchange. After gas exchange, oxygen-rich blood returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins before being distributed systemically. The bronchial arteries, which are part of the systemic circulation, provide blood supply to the bronchi. The pulmonary circulation operates under low pressure (approximately one-tenth of systemic circulation), low resistance, and high capacity, facilitating effective gas exchange while filtering particulate matter returning via the venous system.

Categories

Based on the anatomical structure and pathophysiological characteristics of the respiratory system, diseases can generally be classified into the following categories:

- Obstructive pulmonary diseases, characterized by airflow limitation.

- Restrictive ventilatory disorders, involving reduced lung volume.

- Pulmonary vascular diseases.

Acquired conditions, such as infections and tumors, are common contributors to respiratory pathology, leading to various pathological changes. Sleep disturbances can also result in respiratory system diseases. These conditions, as they progress, may ultimately lead to acute or chronic respiratory failure.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of respiratory system diseases often involves multiple dimensions. A detailed patient history and physical examination form the foundation. Imaging studies, including X-rays and CT scans, and pulmonary function tests play a significant role in diagnosis. Laboratory investigations, ranging from routine to specialized blood and microbiological tests, are also of great diagnostic value. Additionally, diagnostic tools such as bronchoscopy and thoracoscopy have become increasingly important for certain respiratory diseases. A comprehensive assessment combining all the above information is generally required to identify key features of the case, distinguish facts from misinterpretations, and achieve an objective and accurate conclusion.

Medical History

A detailed medical history helps in understanding the causes of respiratory diseases and the course of the condition. According to principles of clinical diagnostics, the history should cover aspects such as environmental or occupational exposure, smoking history, history of contact with infectious diseases, past medical history, medication history, and family history of hereditary diseases.

Symptoms

Local symptoms of the respiratory system primarily include cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and chest pain. These symptoms exhibit distinct characteristics depending on the specific lung disease.

Cough

Cough is the most common symptom of respiratory diseases. It is classified into the following types based on its duration:

- Acute Cough (≤3 weeks): Often associated with acute injury or inflammatory conditions of the respiratory tract or lung parenchyma, such as acute upper respiratory tract infections, acute tracheitis, bronchitis, or pneumonia. Acute cough is commonly accompanied by fever.

- Subacute Cough (3–8 weeks): Frequently observed following a common cold (also known as post-infectious cough), bacterial sinusitis, asthma, and other related conditions.

- Chronic Cough (>8 weeks): May be caused by various conditions and can generally be classified into two types. One type involves clear abnormalities on chest imaging, such as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, interstitial lung diseases, tuberculosis, and lung cancer, often accompanied by symptoms like sputum production, hemoptysis, and shortness of breath. The other type presents with no significant abnormalities on chest imaging and cough is the primary or sole symptom, referred to as unexplained chronic cough (commonly chronic cough). This type is frequently associated with conditions such as upper airway cough syndrome (UACS, formerly known as postnasal drip syndrome), cough variant asthma (CVA), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), eosinophilic bronchitis, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)-induced cough.

Expectoration

The quantity, character, and odor of sputum provide important clues for diagnosis. White, mucoid sputum is often associated with viral, mycoplasma, or chlamydial infections. Yellow, purulent sputum or sputum that transitions from white and mucoid to yellow and purulent often suggests a bacterial infection. Rust-colored sputum may indicate pneumococcal infection. Large amounts of purulent sputum are commonly seen in lung abscesses or bronchiectasis. Red-brown, jelly-like sputum may indicate Klebsiella pneumonia infection, while foul-smelling sputum suggests the presence of anaerobic infections. Chocolate-colored sputum with a fishy odor may indicate pulmonary amebiasis. Pink, frothy sputum accompanied by shortness of breath may suggest heart failure and pulmonary edema. The increase or decrease in sputum volume may reflect the exacerbation or resolution of infection, respectively. A sudden reduction in sputum production accompanied by fever may indicate poor bronchial drainage.

Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis refers to the expectoration of blood originating from damaged blood vessels in the airways or lung parenchyma. It can result from various causes such as acute bronchitis, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, pulmonary fungal infections, or lung cancer. Hemoptysis is often mild or moderate, presenting as blood-streaked sputum, blood-tinged sputum, or fresh blood, but 5–15% of cases involve massive hemoptysis, which may be life-threatening. The severity is typically determined by the volume and rate of bleeding. Small-volume hemoptysis is generally defined as less than 100 mL within 24 hours or less than 30 mL during a single episode, while massive hemoptysis is often defined as more than 500 mL in 24 hours or more than 100 mL during a single episode. Massive hemoptysis, commonly seen in bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, or fungal infections, necessitates urgent medical attention.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is often described as chest tightness or shortness of breath and may involve changes in the rate, depth, or rhythm of breathing. It is classified based on its onset as acute, chronic, or recurrent. Acute dyspnea following sudden chest pain suggests pneumothorax, and if accompanied by hemoptysis, acute pulmonary embolism should be considered. Recurrent dyspnea accompanied by wheezing is often indicative of bronchial asthma. Nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea suggests left heart failure or an acute asthma attack. Gradual onset of progressive dyspnea over days or weeks may point to pneumonia or pleural effusion. Chronic and progressively worsening dyspnea is often associated with conditions such as COPD or interstitial lung diseases like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An analysis of whether dyspnea is inspiratory or expiratory provides additional diagnostic insights. Inspiratory dyspnea is commonly linked to upper airway obstruction caused by tumors, foreign bodies, laryngeal edema, or laryngeal/tracheal inflammation, whereas expiratory dyspnea is typically seen in asthma or COPD.

Chest Pain

The lung parenchyma lacks pain receptors, so chest pain usually arises from pleural involvement or muscle strain due to cough. Pleuritic chest pain is often unilateral, more noticeable at the end of inspiration, and relatively localized, as seen in pneumothorax, pneumonia, tumors, and pulmonary embolism. Severe pulmonary hypertension can lead to myocardial ischemia, resulting in dull, non-respiratory chest pain in the precordial area. Among causes of chest pain unrelated to the respiratory system, angina pectoris and myocardial infarction are particularly notable and are characterized by squeezing pain behind the sternum or in the left anterior chest, sometimes radiating to the left shoulder. Additionally, conditions like pericarditis and aortic dissection can also cause chest pain. Intercostal neuralgia, costochondritis, shingles, and Coxsackie virus infections may present as superficial chest wall pain. Abdominal organ diseases such as cholelithiasis and acute pancreatitis may occasionally cause pain referred to different chest regions, necessitating careful differentiation.

Physical Signs

Respiratory system diseases may manifest physical signs not only in the respiratory system but also in other bodily systems. Physical examinations should therefore include a thorough chest examination as well as assessments of the body as a whole, including the eyes, lips, trachea, jugular veins, bones, joints, and fingers (or toes). Inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation of the chest are conducted with attention to bilateral comparison, allowing for the identification of abnormal findings. Chest signs may range from completely normal to significantly abnormal depending on the type, extent, and stage of the disease. In lung auscultation, the term "crackles" has replaced the previously used term "rales."

Fine crackles are non-musical sounds heard during the late inspiratory phase and are commonly associated with heart failure or interstitial lung diseases. Characteristic "Velcro-like" crackles may be observed in pulmonary fibrosis.

Coarse crackles sound as though transmitted through the oral cavity, become clearer after coughing, and are frequently associated with conditions such as bronchitis.

Wheezes are high-pitched, musical sounds that are more pronounced during the expiratory phase, although they may also be heard during inspiration. They are commonly observed in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Rhonchi are low-pitched, musical sounds that are more pronounced during expiration but may also occur during inspiration and often disappear with coughing. They are typically found in patients with bronchitis.

Stridor is a high-pitched, musical sound that can usually be heard without a stethoscope. It suggests upper airway obstruction, as seen in acute laryngitis, tracheal tumors, or tracheal compression by intrathoracic masses.

Absent breath sounds may indicate complete airway obstruction or a large pleural effusion.

Pleural friction rubs are commonly associated with pleuritis.

Laboratory and Auxiliary Tests

Appropriate laboratory investigations tailored to the clinical presentation can aid in identifying the underlying cause of illness and assessing disease activity or severity.

Laboratory Tests

Routine Tests

Abnormalities in blood counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels may suggest infections or non-infectious inflammation. Elevated white blood cell counts, particularly neutrophils, often suggest bacterial infections. Lymphocytopenia is commonly associated with viral infections, whereas eosinophilia may indicate parasitic infections or allergic diseases.

Sputum Analysis

Deep sputum samples are most diagnostically meaningful when obtained after oral rinsing and are considered qualified if epithelial cell counts are <10 per low-power field, white blood cell counts are >25 per low-power field, or the WBC-to-epithelial cell ratio exceeds 2.5. For patients who do not produce sputum, hypertonic saline nebulization may be used to induce sputum.

Pathogen Detection

A sputum smear with Gram staining, acid-fast staining, and culture can provide critical information for diagnosing pulmonary infections. For example:

- The presence of acid-fast bacilli on sputum smear strongly suggests tuberculosis; confirmation relies on culturing Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Detection or culture of filamentous fungi in sputum suggests pulmonary fungal infections.

- Quantitative bacterial culture yielding ≥107 colony-forming units (cfu)/mL signifies a pathogenic organism, while 104–107 cfu/mL indicates a possible pathogen, and <104 cfu/mL suggests contamination with oral flora.

Cytological Analysis

An increase in eosinophils in sputum points toward eosinophilic bronchitis. Cytological examination of exfoliated sputum cells aids in diagnosing malignant pulmonary tumors.

Microbiological Testing

Specimens for microbiological examination in respiratory diseases may include sputum, blood, throat swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, bronchial brushings, or biopsy of lung tissues. Key diagnostic methods include:

- Conventional smears and specialized staining techniques to identify pathogens, such as Gram-positive/negative bacteria or acid-fast bacilli.

- Microbial culture.

- Immunological methods to detect antigens, antibodies, or immune responses to pathogens (e.g., viruses, mycoplasma, Legionella, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, fungi). Rising antibody titers in convalescent-phase sera are particularly significant diagnostically.

- Nucleic acid testing, including PCR or RT-PCR, to detect pathogen-specific nucleic acids.

- Testing for biomarkers of pathogen infections, such as procalcitonin (PCT) for bacterial infections or fungal antigens, including 1,3-beta-D-glucan (G test) and galactomannan (GM test) for aspergillosis.

- Metagenomics sequencing can be helpful in cases of unexplained infections or inflammatory lesions in the lung, providing insights into whether an infection is present and identifying potential pathogens.

Non-Infectious Biological Markers

For suspected rheumatologic or autoimmune diseases, assessment may include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

For suspected malignancies, tumor markers and circulating tumor cells may be evaluated.

Radiological Examinations

Radiological diagnosis holds significant importance in the evaluation and management of respiratory system diseases. It involves analyzing imaging characteristics to infer pathological changes and identifying the anatomical location of abnormalities to deduce the affected tissues or organs. A thorough understanding of the anatomy of thoracic organs, pathological features of various diseases, and corresponding imaging patterns forms the basis for accurate radiological diagnoses, which must also take clinical manifestations into account.

Chest X-ray (CXR)

Chest X-rays are commonly used to determine the location, nature, and clinical context of respiratory diseases.

Chest CT

Chest CT scans are particularly valuable for detecting abnormalities not visible on X-rays, pinpointing the location and nature of lung lesions, and evaluating the patency of airways such as the trachea and bronchi. Contrast-enhanced CT plays a critical role in diagnosing lymphadenopathy and pulmonary masses. CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) can detect thrombi at the segmental or subsegmental level within pulmonary arteries and is an essential tool for confirming pulmonary embolism. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is indispensable for diagnosing interstitial lung diseases and is also an important tool for assessing bronchiectasis. Low-dose CT is utilized for early lung cancer screening, aiming to minimize radiation exposure.

Chest MRI

Chest MRI offers unique advantages in diagnosing vascular abnormalities, lesions in the supraclavicular fossa, mediastinal abnormalities, pleural diseases, and chest wall conditions. However, its utility in diagnosing lung parenchymal diseases is limited compared to CT.

Radionuclide Scanning

Ventilation and perfusion scans of the lungs provide diagnostic value in pulmonary embolism and vascular abnormalities. Whole-body bone scans have significant utility in identifying bone metastases from pulmonary malignancies.

Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT)

PET-CT evaluates the metabolic activity of lesions by assessing their uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). It helps identify the location and extent of lesions, estimate their nature, and distinguish between benign and malignant conditions. This is particularly useful in the differential diagnosis of lung malignancies, mediastinal lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.

Chest Ultrasound

Chest ultrasound is utilized for diagnosing pleural effusion, guiding pleural fluid aspiration, and performing biopsy procedures on lesions closely attached to the pleura.

Pulmonary/Bronchial Arteriography and Embolization

These techniques provide valuable information for classifying pulmonary hypertension and are highly effective for managing and diagnosing cases of hemoptysis.

Antigen Skin Tests

Positive allergen skin tests in asthma indicate an atopic predisposition and can guide desensitization therapy against specific antigens. A positive tuberculin skin test (PPD test) suggests previous infection or Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination but does not confirm active tuberculosis.

Respiratory Function Tests

Respiratory function tests, including arterial blood gas analysis, pulmonary function tests, and the six-minute walk test, contribute to understanding the type and extent of lung function impairment caused by respiratory diseases. These tests are crucial for the early diagnosis of certain pulmonary conditions:

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis identifies hypoxia, respiratory failure, hypercapnia, and acid-base imbalances.

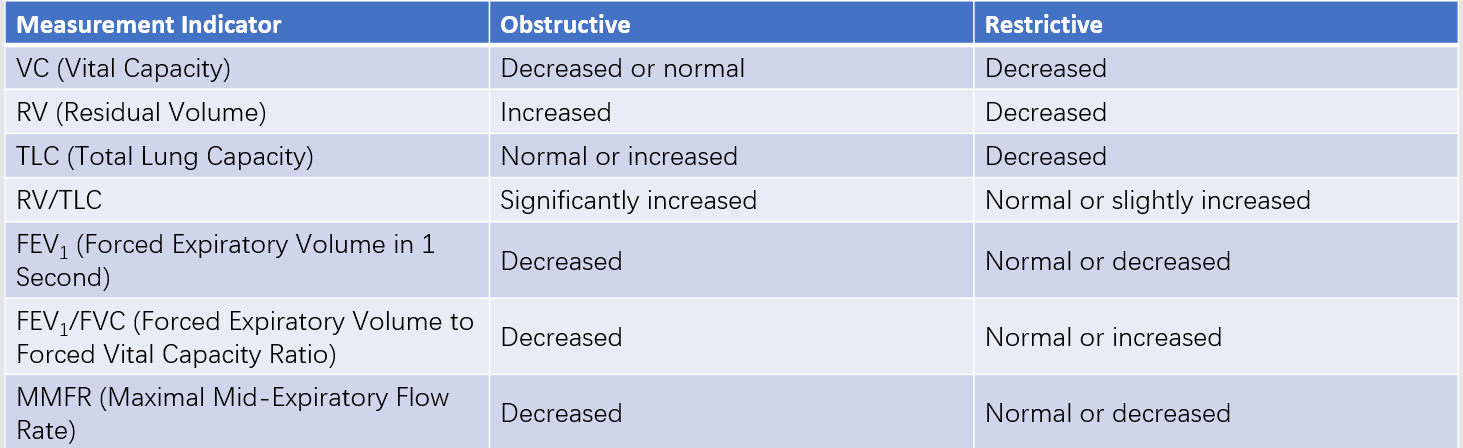

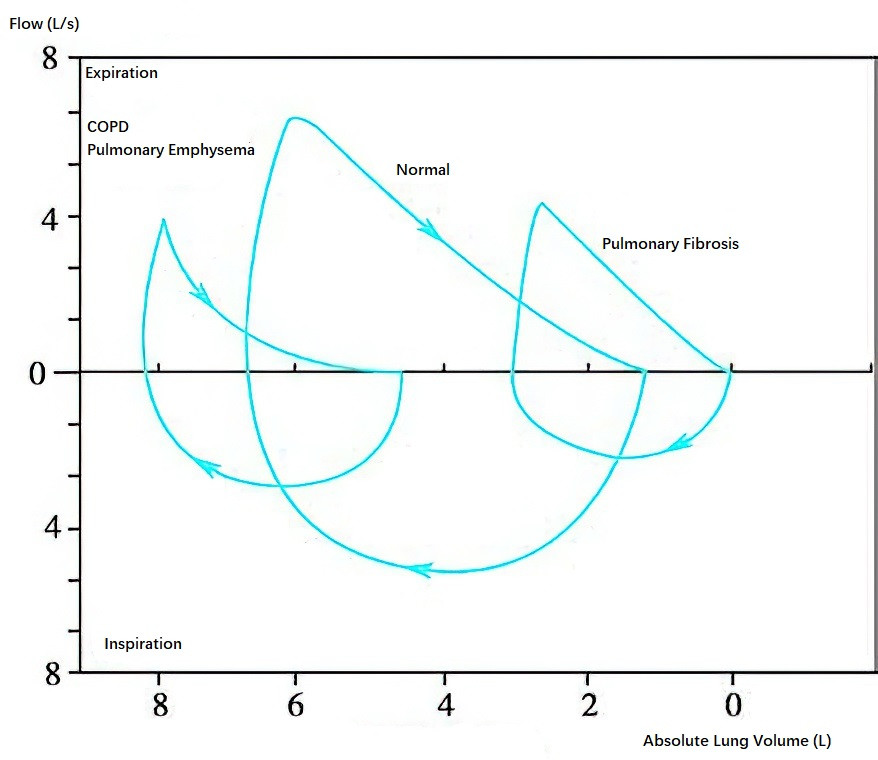

Pulmonary Function Tests primarily assess ventilatory function and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Measurements include forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and peak expiratory flow (PEF). Ventilatory dysfunction is classified as obstructive, restrictive, or mixed:

Table 1 Characteristic changes in lung volumes and ventilatory function in obstructive and restrictive pulmonary ventilatory disorders

Figure 2 Typical flow-volume curves during forced inspiration and expiration in normal individuals, patients with COPD, and patients with pulmonary fibrosis

Obstructive ventilatory dysfunction commonly occurs in small airway diseases such as COPD and asthma.

Restrictive ventilatory dysfunction is seen in conditions that decrease lung compliance, including interstitial lung diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis) or extrapulmonary conditions (e.g., pleural effusion, pleural thickening, thoracic deformities, or respiratory muscle dysfunction).

DLCO testing helps determine gas exchange impairment, particularly in interstitial lung and vascular diseases. Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is another method for detecting airflow limitation and is suitable for self-monitoring by patients.

The Six-Minute Walk Test provides a comprehensive evaluation of cardiopulmonary function in patients with respiratory diseases and helps assess disease severity and response to treatment.

Thoracentesis and Pleural Biopsy

Thoracentesis determines the nature of pleural effusion, with routine and biochemical tests (e.g., protein, glucose, and lactate dehydrogenase) aiding in differentiating exudative from transudative effusions. Elevated levels of adenosine deaminase or a positive interferon-gamma release assay in pleural fluid suggest tuberculous pleuritis. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytological examination, and chromosomal analysis support the diagnosis of malignant pleural effusion. Pleural biopsy is valuable in diagnosing tumors or tuberculosis-related pleural lesions.

Bronchoscopy and Thoracoscopy

Flexible Fiberoptic or Electronic Bronchoscope

Flexible fiberoptic or electronic bronchoscopes are capable of navigating the airways down to the subsegmental bronchi. These tools provide direct visualization of lesions and enable procedures such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), bronchial mucosal brushing and biopsy, transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC), and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-guided needle aspiration from mediastinal masses or lymph nodes (EBUS-TBNA). The bronchoalveolar lavage fluid as well as bronchial mucosal or lung tissue specimens obtained through these techniques can be analyzed using cytological, pathological, and microbiological methods, aiding in the diagnosis of diseases.

Recently developed technologies, such as radial probe endobronchial ultrasonography (RP-EBUS) and electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB), facilitate bronchoscope-guided biopsies for peripheral pulmonary lesions, assisting in the determination of disease characteristics. Flexible bronchoscopes also have therapeutic applications, including the removal of foreign bodies, hemostasis, and treatment of benign or malignant tumors using high-frequency electrocautery, laser, microwave therapy, or medication injection. Guided tracheal intubation can also be performed using a flexible bronchoscope.

Rigid Bronchoscope

Rigid bronchoscopes have wider lumens and are now often used in conjunction with flexible bronchoscopes. They are primarily employed in complex interventional airway procedures, such as tumor resection under direct visualization or tracheal stent placement.

Thoracoscopy

Thoracoscopy allows direct visualization of pleural abnormalities and facilitates pleural and lung biopsies. It also enables the performance of pleurodesis.

Lung Biopsy

Lung biopsy is a crucial method for confirming the diagnosis of pulmonary diseases. Methods for obtaining lung tissue samples include:

- Endoscopic approaches, including bronchoscopy, thoracoscopy, or mediastinoscopy.

- Percutaneous lung biopsy performed under X-ray or CT guidance, suitable for pulmonary lesions that are not adjacent to the heart or major blood vessels.

- Ultrasound-guided percutaneous lung biopsy, appropriate for lesions located near the pleura.

- Open lung biopsy or video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy (VATS), which are particularly suitable for diagnosing certain interstitial lung diseases or cases where other biopsy methods fail to provide a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

The treatment approaches for respiratory system diseases vary depending on the specific condition. The general principle is based on an integrated six-pronged strategy emphasizing prevention, diagnosis, control, treatment, and rehabilitation to promote respiratory health.

Elimination of Causes or Avoidance of Risk Factors

Respiratory diseases caused by exposure to harmful or irritating substances, such as silicosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis, rely on etiological treatment primarily focused on avoiding the environment that triggers the disease.

Symptomatic Treatment for Cough and Sputum Clearance

Cough serves as a protective reflex but can significantly affect quality of life. Depending on the severity and characteristics of the condition, central or peripheral antitussive medications may be used for treatment. Commonly used expectorants include mucolytic agents, which act on the disulfide bonds in mucin, breaking them to reduce the viscosity of sputum. Frequently used medications include ambroxol, acetylcysteine, and carbocisteine.

Treatment Based on Etiology or Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Antibiotics

Infectious respiratory diseases may be caused by pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, mycoplasma, chlamydia, fungi, or parasites. Treatment involves selecting antibiotics based on the sensitivity of the pathogen. In addition to referring to antimicrobial susceptibility test results, consideration is given to the patient's organ function and the pharmacokinetic properties of the antibiotics. Details are covered in the chapter on pulmonary infections.

Bronchodilators

This group includes β2-agonists (short-acting and long-acting), cholinergic receptor antagonists (short-acting and long-acting), and methylxanthines. These agents are primarily used to dilate the airways and treat airway obstruction in diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The selection of formulations, dosages, and treatment strategies depends on the specific presentation and severity of the disease.

Anti-inflammatory Agents

Corticosteroids are used to treat conditions such as asthma and COPD, often in inhaled formulations. For interstitial lung diseases and pulmonary vasculitis, systemic corticosteroid therapy is more commonly employed. Prolonged corticosteroid use requires monitoring of blood pressure, blood glucose, and lipid levels. For patients using oral corticosteroids for more than three months, bisphosphonates are recommended to prevent osteoporosis. Leukotriene receptor antagonists serve as adjunctive therapy for asthma and are particularly effective in aspirin-induced asthma. Biologic agents, such as anti-IgE monoclonal antibodies, anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies, anti-IL-5 receptor monoclonal antibodies, and anti-IL-4 receptor monoclonal antibodies, are currently utilized to manage severe asthma that cannot be controlled by standard treatments. Further information can be found in the relevant chapters.

Anti-fibrotic Therapy

Additional details are provided in the chapter on interstitial lung diseases.

Anticoagulant or Thrombolytic Therapy

Information on this treatment can be found in the chapter on pulmonary embolism.

Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer

Specific therapeutic details are covered in the chapter on lung cancer.

Interventional Respiratory Procedures

These include procedures performed with bronchoscopes and related techniques, such as the removal of airway foreign bodies, resection of tumors, or stent insertion to manage bronchial stenosis.

Oxygen Therapy or Respiratory Support Therapy

Further details are available in the chapters on respiratory failure and sleep-disordered breathing.

Lung Transplantation

Lung transplant evaluation is considered for patients with end-stage lung diseases who meet the criteria and have access to the requisite resources.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation Therapy

Rehabilitation therapy tailored to the patient's condition is conducive to recovery, helping improve their quality of life.