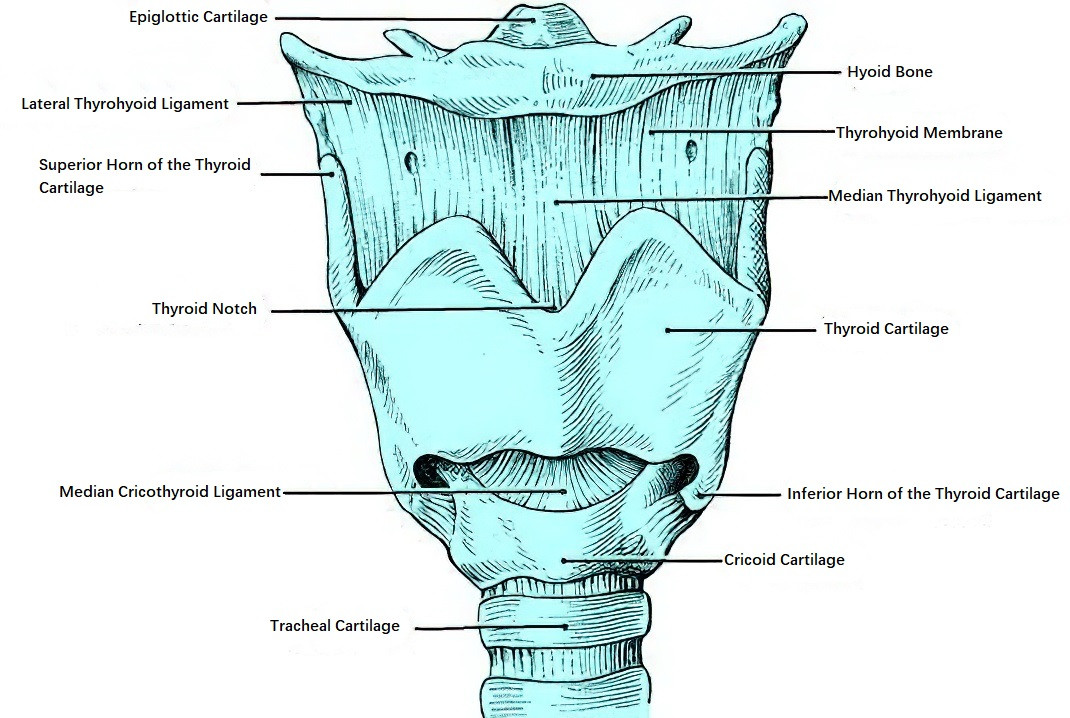

The larynx serves as both a crucial organ for phonation and an essential airway passage. It acts as the gateway to the lower respiratory tract, connecting to the laryngopharynx above and the trachea below. Situated in the anterior midline of the neck, beneath the hyoid bone, the larynx extends from the superior border of the epiglottis at its upper end to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage at its lower end. In adults, the larynx is approximately aligned with the C3–C5 vertebral level, though its position is slightly higher in women and children compared to men. The larynx is composed of cartilage, muscles, ligaments, fibrous connective tissue, and mucosa. Anteriorly, the larynx is covered by skin, subcutaneous tissue, cervical fascia, and strap muscles, while its lateral aspects are flanked by the upper poles of the thyroid gland, the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and underlying major neurovascular structures. Posteriorly, it is adjacent to the laryngopharynx and cervical vertebrae.

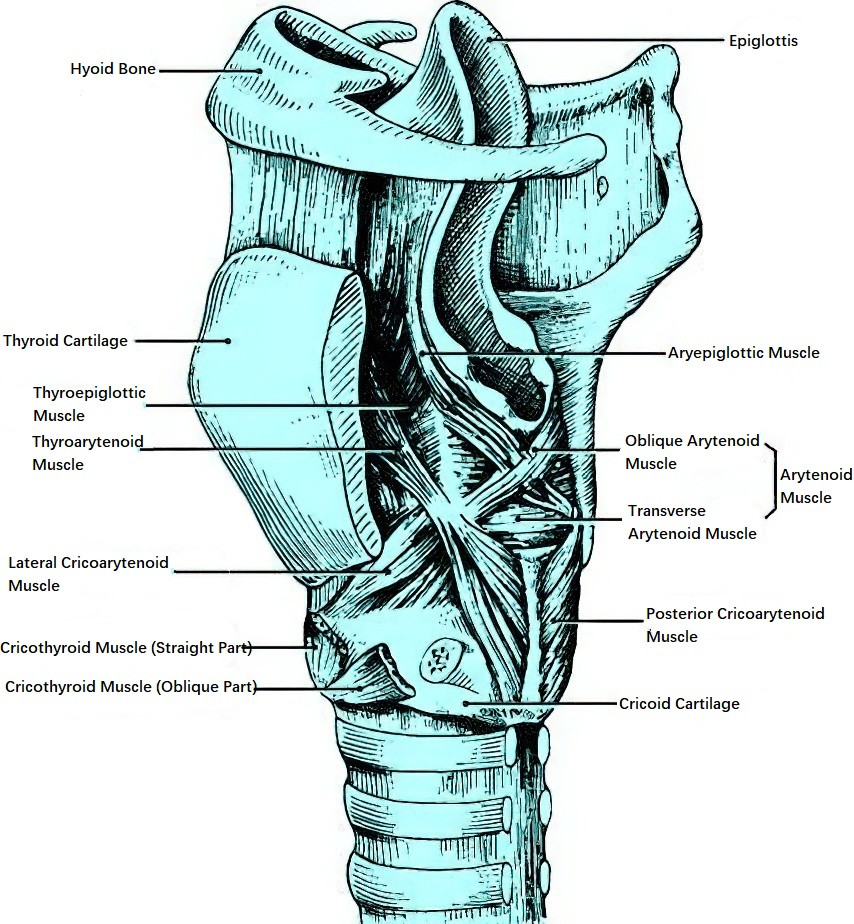

Figure 1 Anterior view of the larynx

Laryngeal Cartilages

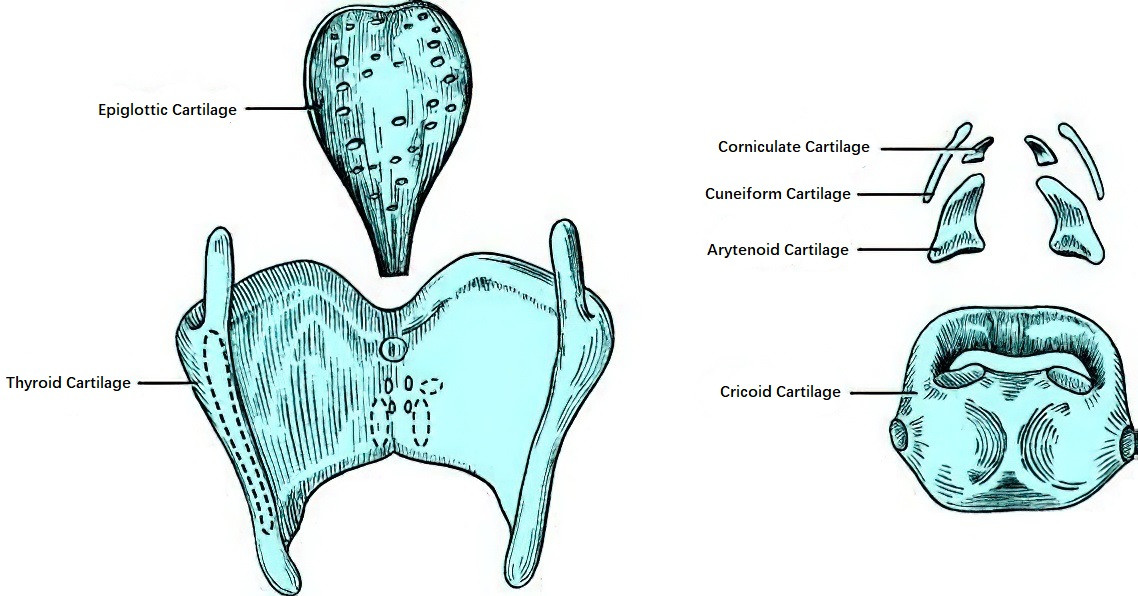

The framework of the larynx is formed by cartilage. There are nine cartilages in total, consisting of three unpaired cartilages—thyroid, cricoid, and epiglottic—and three paired cartilages—arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform. The corniculate and cuneiform cartilages are relatively small and have limited clinical significance.

Figure 2 Laryngeal cartilages

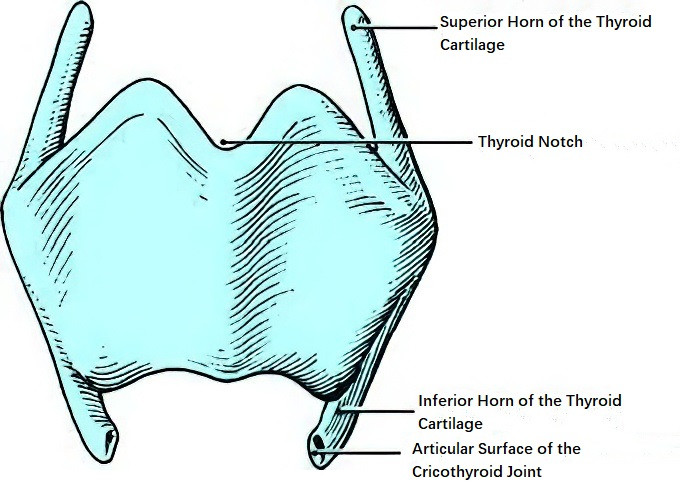

Thyroid Cartilage

The thyroid cartilage is the largest cartilage of the larynx. It is formed by two quadrilateral plates of thyroid cartilage that fuse in the midline anteriorly, creating the primary structural component of the laryngeal framework alongside the cricoid cartilage. In males, the anterior angle of the thyroid cartilage is sharper, forming an acute or right angle, and its upper portion protrudes forward to form the "Adam’s apple," a characteristic feature of adult males. In females, the angle is closer to obtuse, making the laryngeal prominence less apparent. The upper midline border of the thyroid cartilage has a V-shaped notch called the thyroid notch. At the posterior edge of each thyroid cartilage plate, there are two protrusions: the superior horn and the inferior horn. The superior horn is longer, while the inferior horn is shorter and articulates with the lateral surface of the cricoid cartilage to form the cricothyroid joint.

Figure 3 Thyroid cartilage

Cricoid Cartilage

The cricoid cartilage, located beneath the thyroid cartilage and above the first tracheal ring, has a shape resembling a ring. Its anterior region, called the cricoid arch, is narrower, while the posterior region, referred to as the cricoid lamina, is broader. The cricoid cartilage is the only complete ring of cartilage in the larynx and trachea, making it essential for maintaining airway patency. Injuries or diseases that compromise the integrity of the cricoid cartilage can lead to stenosis of both the larynx and trachea.

Figure 4 Cricoid cartilage

Epiglottic Cartilage

The epiglottic cartilage, typically leaf-shaped and slightly curved, is relatively rigid. Its surface features small perforations that allow small blood vessels and nerves to pass through, connecting the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis with the pre-epiglottic space. The lower portion of the epiglottic cartilage, known as the epiglottic stalk, is narrower. This cartilage is located in the upper portion of the larynx and is covered by mucosa, forming the epiglottis. During swallowing, the epiglottis covers the opening of the larynx, preventing food or liquid from entering the airway. The epiglottis has two surfaces: the lingual surface and the laryngeal surface. The lingual surface has loose connective tissue, which can swell easily in cases of infection. The mucosa on the lingual surface forms the glossoepiglottic fold in the midline between the epiglottis and tongue base, while the two lateral depressions in this area are called the valleculae. In children, the epiglottis is more curved.

Arytenoid Cartilages

The arytenoid cartilages, situated on the posterolateral edges of the cricoid lamina, are paired and pyramid-shaped. The base of each arytenoid cartilage articulates with the cricoid cartilage at the cricoarytenoid joint, allowing for both gliding and rotational movements. These movements enable the arytenoid cartilages to control the adduction and abduction of the vocal cords. The anterior projection at the base of the arytenoid cartilage, known as the vocal process, serves as the attachment site for the vocal ligament and thyroarytenoid muscle. The lateral projection, termed the muscular process, provides attachment sites for the posterior cricoarytenoid and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles.

Corniculate Cartilages

The corniculate cartilages, one on each side, are small structures located at the apices of the arytenoid cartilages. They are embedded within the aryepiglottic fold.

Cuneiform Cartilages

The cuneiform cartilages, also paired, are rod-shaped structures located anterolateral to the corniculate cartilages. They lie beneath the mucosa of the aryepiglottic folds and form small, white elevations within the folds, known as the cuneiform tubercles.

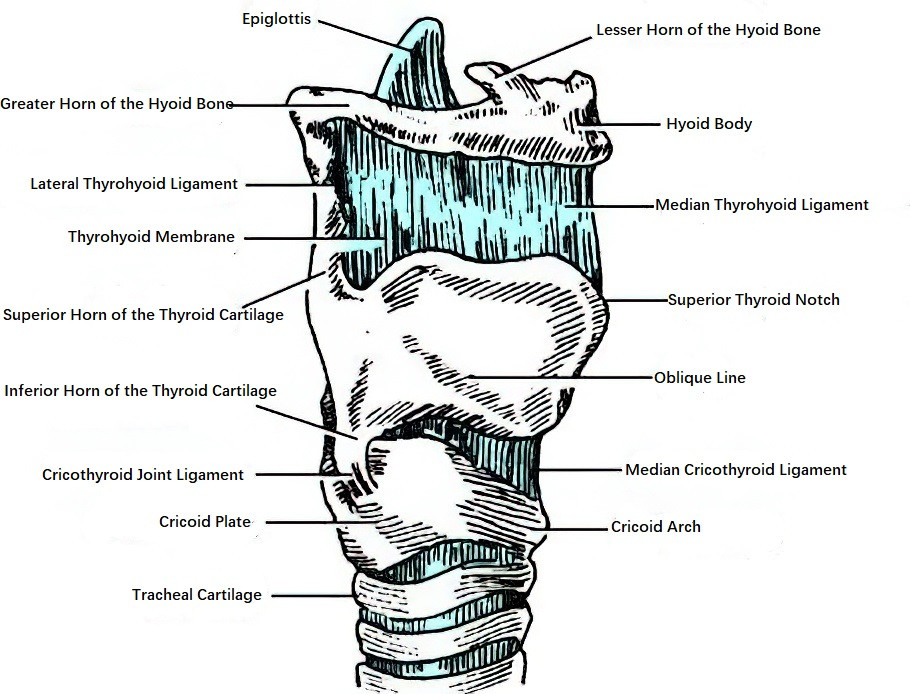

Laryngeal Ligaments and Membranes

Fibrous ligaments connect the various cartilages of the larynx, as well as the larynx to surrounding structures such as the hyoid bone, the tongue, and the trachea.

Thyrohyoid Membrane

Also known as the thyrohyoid ligament or hyothyroid membrane, it is an elastic fibrous ligament spanning between the upper edge of the thyroid cartilage and the lower edge of the hyoid bone. The membrane thickens medially and laterally to form the median thyrohyoid ligament and the lateral thyrohyoid ligaments, respectively. The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve, along with the superior laryngeal artery and vein, passes through the thyrohyoid membrane on each side to enter the larynx.

Figure 5 Right lateral view of the larynx (showing laryngeal ligaments and membranes)

Cricothyroid Membrane

This fibrous ligament connects the upper edge of the cricoid cartilage arch to the lower edge of the thyroid cartilage. Its central portion thickens to form the median cricothyroid ligament.

Thyroepiglottic Ligament

This ligament connects the stalk of the epiglottis to the posterior inferior aspect of the thyroid cartilage notch.

Capsular Ligament of the Cricothyroid Joint

This ligament envelopes the external surface of the cricothyroid joint.

Posterior Cricoarytenoid Ligament

Positioned posterior to the cricoarytenoid joint, this ligament supports the movement of the joint.

Hyoepiglottic Ligament

This fibrous ligament connects the lingual surface of the epiglottis, the hyoid bone body, and the greater horns of the hyoid bone. The epiglottis, the hyoepiglottic ligament, and the central part of the thyrohyoid membrane together form the preepiglottic space, which contains adipose tissue.

Glossoepiglottic Ligament

This ligament connects the midline of the lingual surface of the epiglottic cartilage to the root of the tongue.

Cricotracheal Ligament

This ligament connects the cricoid cartilage to the upper border of the first tracheal ring.

Elastic Membrane of the Larynx

A broad elastic structure, there are two elastic membranes, one on each side of the larynx. They are divided into superior and inferior parts by the laryngeal ventricle.

Quadrangular Membrane

The superior part of the elastic membrane stretches between the lateral margin of the epiglottic cartilage and the vocal processes of the arytenoid and corniculate cartilages. Its upper and lower edges are free. The upper edge forms the aryepiglottic ligament, while the lower edge forms the vestibular ligament. When covered by mucosa, these correspond to the aryepiglottic fold and vestibular fold (false vocal cord). The lateral surface of the quadrangular membrane, covered with mucosa, forms the upper part of the medial wall of the piriform recess.

Elastic Cone (Conus Elasticus)

The inferior part of the elastic membrane extends from near the midline of the inner surface of the angle formed by the thyroid cartilage to the lower border of the arytenoid vocal process posteriorly. Its free edge thickens to form the vocal ligament, and its attachment to the upper part of the cricoid cartilage forms the cricothyroid membrane, with the central part thickened as the median cricothyroid ligament.

Figure 6 Elastic cone of the larynx

Laryngeal Muscles

The muscles of the larynx are divided into extrinsic muscles and intrinsic muscles. The extrinsic muscles are located externally and connect the larynx to surrounding structures, allowing for its elevation, depression, or stabilization. Most intrinsic muscles are located within the laryngeal framework (except for the cricothyroid muscle) and are primarily responsible for vocal cord movement.

Extrinsic Muscles

These can be grouped into elevators and depressors of the larynx:

- Elevators: Include the thyrohyoid muscle, mylohyoid muscle, digastric muscle, and stylohyoid muscle.

- Depressors: Include the sternothyroid muscle, sternohyoid muscle, omohyoid muscle, and the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

Intrinsic Muscles

These can be classified into five functional groups:

Figure 7 Oblique section of the larynx showing internal laryngeal muscles

Figure 8 Diagram of the functional roles of laryngeal muscles

Abductor of the Vocal Cords

Posterior Cricoarytenoid Muscle

This muscle originates from the shallow depressions on the posterior surface of the cricoid cartilage lamina and inserts into the posterior surface of the arytenoid muscle process. Its contraction moves the arytenoid cartilages outward and slightly upward, abducting the vocal cords and widening the glottis.

Adductors of the Vocal Cords

Lateral Cricoarytenoid Muscle

This originates from the upper border of the cricoid cartilage arch and inserts into the anterior lateral surface of the arytenoid muscular process.

Arytenoid Muscle

This consists of transverse and oblique fibers (referred to as the transverse arytenoid and oblique arytenoid muscles). These muscles are attached between the two arytenoid cartilages. Contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle and arytenoid muscle adducts the vocal cords, closing the glottis.

Tensors of the Vocal Cords

Cricothyroid Muscle

This muscle originates from the anterolateral arch of the cricoid cartilage and inserts into the inferior edge of the thyroid cartilage. When contracting, it shortens the distance between the lower edge of the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid arch while increasing the distance between the anterior thyroid cartilage and the arytenoid cartilage, tightening the vocal ligament and increasing vocal cord tension.

Relaxers of the Vocal Cords

Thyroarytenoid Muscle

This muscle originates from the central anterior inner surface of the thyroid cartilage and inserts into the vocal and muscular processes of the arytenoid cartilage. Contraction shortens the vocal cords, adjusts vocal cord tension, and also assists with vocal cord adduction and glottal closure.

Muscles that Move the Epiglottis

Aryepiglottic Muscle

Contraction draws the epiglottis backward and downward toward the laryngeal inlet, closing it.

Thyroepiglottic Muscle

Contraction draws the epiglottis upward and forward, opening the laryngeal inlet.

Laryngeal Mucosa

The majority of the laryngeal mucosa is lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. However, the medial surface of the vocal cords, most of the lingual surface of the epiglottis, and the mucosa of the aryepiglottic folds are covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Certain regions, including the lingual surface of the epiglottis, the subglottic region, the arytenoid region, and the aryepiglottic folds, possess loose submucosal layers, which are prone to swelling during inflammation and may result in airway obstruction. The mucosa of the larynx is rich in mucus-secreting glands, especially in areas such as the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis and the laryngeal ventricles.

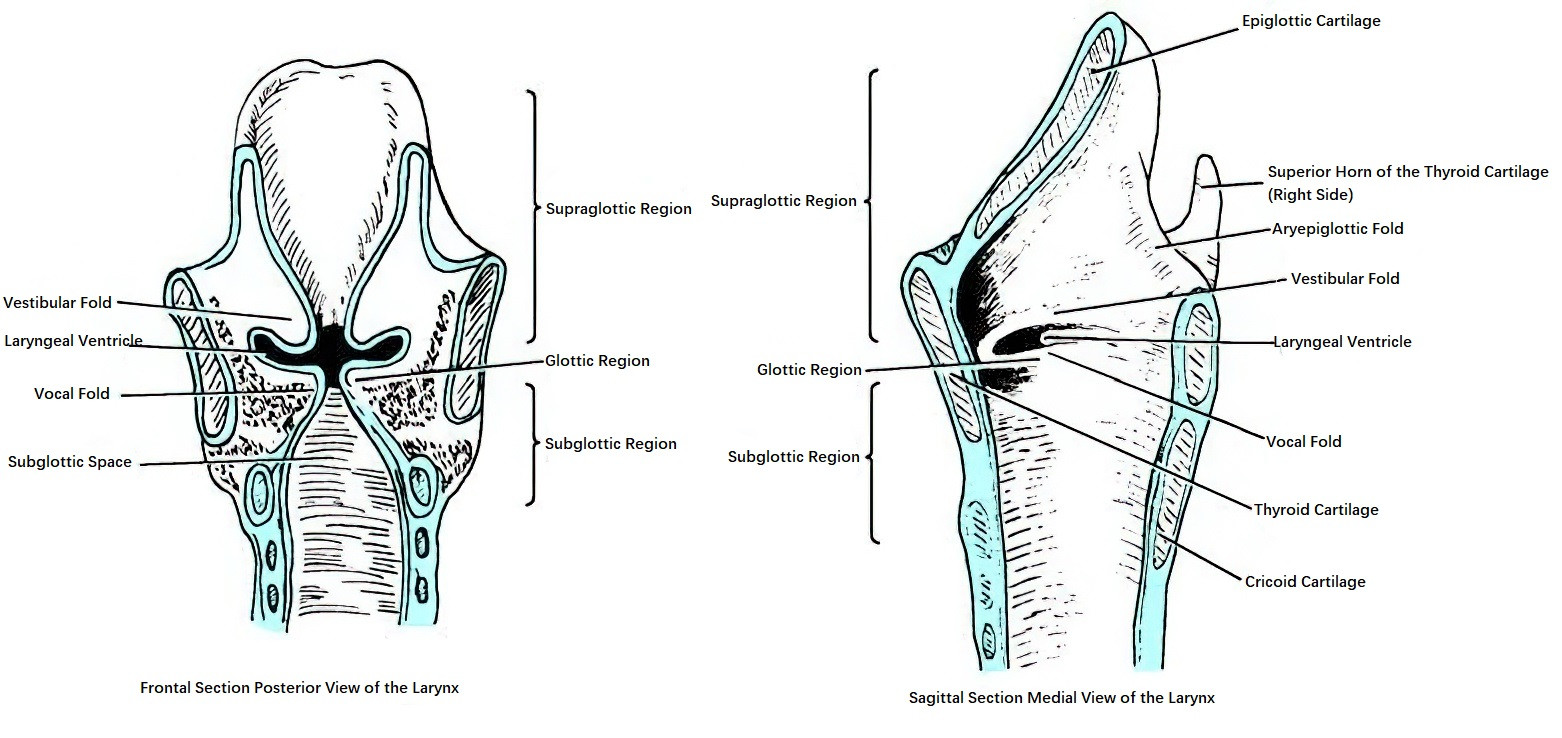

Laryngeal Cavity

The upper boundary of the laryngeal cavity is the laryngeal inlet, which is formed by the free edge of the epiglottis, the paired aryepiglottic folds, the arytenoid regions, and the interarytenoid space. Its lower boundary is the inferior edge of the cricoid cartilage. Two pairs of soft tissue elevations are located on the lateral walls of the laryngeal cavity. The upper pair is called the vestibular folds or false vocal cords, while the lower pair is referred to as the vocal folds or true vocal cords. The opening between the two vocal folds is known as the rima glottidis. The space between the vestibular folds and vocal folds is called the laryngeal ventricle.

The histological structure of the vocal folds is as follows:

The mucosa near the free edge of the medial surface of the vocal cord is made up of stratified squamous epithelium, while the lateral part consists of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. Beneath the mucosa, the lamina propria is divided into three layers:

- The superficial layer, also called Reinke’s space, is a thin and loose layer of fibrous tissue, which is easily susceptible to localized edema (e.g., vocal cord polyps) during overuse or inflammation.

- The intermediate layer contains elastic fibers.

- The deep layer is composed of dense collagen fibers.

Beneath the lamina propria is the muscular layer, which corresponds to the medial portion of the thyroarytenoid muscle. The epithelium and superficial lamina propria together form the cover of the vocal fold. The intermediate and deep layers of the lamina propria constitute the vocal ligament, while the vocal ligament and the underlying muscular layer form the body of the vocal fold.

The laryngeal cavity can be divided into three regions based on the location of the vocal folds:

- Supraglottic Region: The portion of the larynx located above the vocal cords, which communicates superiorly with the laryngopharynx.

- Glottic Region: The area between the vocal folds.

- Subglottic Region: The portion of the larynx located below the vocal cords, which is continuous inferiorly with the trachea.

Figure 9 Divisions of the laryngeal cavity

In recent years, increased attention has been directed toward the paraglottic space, whose boundaries are as follows: anteriorly and laterally by the thyroid cartilage, inferiorly and medially by the elastic cone (conus elasticus), and posteriorly by the mucosa of the piriform recess. Tumors originating in the laryngeal ventricle often spread laterally into the paraglottic space.

Vascular Supply of the Larynx

Arteries

Superior Laryngeal Artery and Cricothyroid Artery

The superior laryngeal artery, a branch of the superior thyroid artery, enters the larynx through the thyrohyoid membrane alongside the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal vein. The cricothyroid artery enters the larynx through the cricothyroid membrane. The upper laryngeal region is primarily supplied by the superior laryngeal artery, while the area around the cricothyroid membrane and the lower anterior larynx is mainly supplied by the cricothyroid artery.

Inferior Laryngeal Artery

The inferior laryngeal artery, a branch of the inferior thyroid artery, enters the larynx posterior to the cricothyroid joint, accompanying the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The lower laryngeal region receives its blood supply primarily from the inferior laryngeal artery.

Veins

The laryngeal veins accompany the corresponding arteries and drain into the superior, middle, and inferior thyroid veins, which ultimately empty into the internal jugular vein.

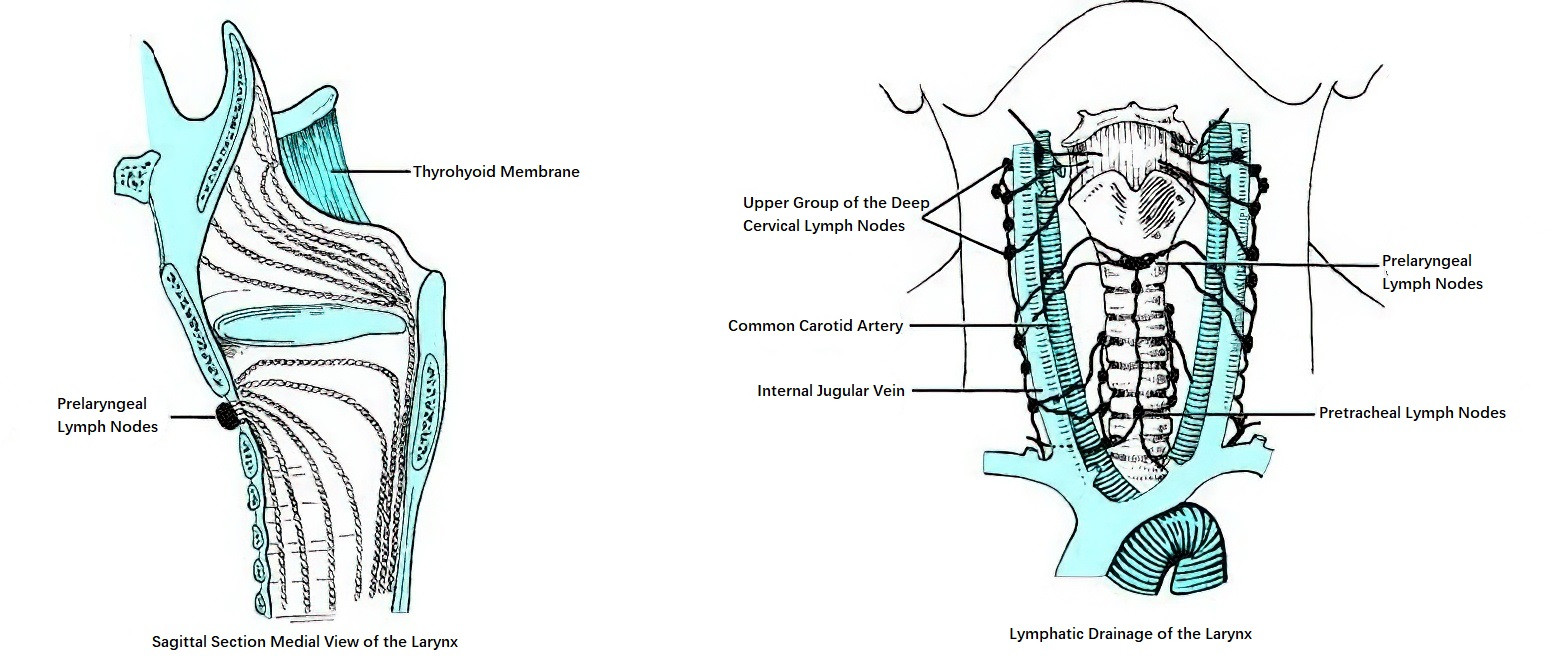

Lymphatics of the Larynx

The lymphatic system of the larynx is divided into two groups based on the glottic region: the supraglottic group and the subglottic group. In the supraglottic region, the tissues are rich in lymphatic vessels, which converge into larger lymphatic channels near the posterior aryepiglottic folds. These vessels pass through the thyrohyoid membrane, accompanying the superior laryngeal artery and vein, and primarily drain into the upper deep cervical lymph nodes located around the internal jugular vein. A smaller portion of the lymphatics flows into the lower deep cervical lymph nodes or the accessory nerve chain. The vocal cords in the glottic region have very few lymphatic vessels. In contrast, the subglottic region contains more lymphatic vessels, which converge and drain through the cricothyroid membrane into the prelaryngeal lymph nodes, pretracheal lymph nodes, and paratracheal lymph nodes, and then into the lower deep cervical lymph nodes.

Figure 10 Lymphatics of the larynx

Innervation of the Larynx

Innervation of the larynx is provided by the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent laryngeal nerve, both of which are branches of the vagus nerve.

Figure 11 Laryngeal nerves (Anterior view)

Figure 12 Laryngeal nerves (Posterior view)

Superior Laryngeal Nerve

The superior laryngeal nerve originates from the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve and descends approximately 2 cm to the level of the greater horn of the hyoid bone, where it divides into an internal branch and an external branch. The internal branch is primarily responsible for sensation, while the external branch is primarily responsible for motor function. The internal branch accompanies the superior laryngeal artery and vein through the thyrohyoid membrane, innervating the mucosa of the supraglottic region and providing sensory input. The external branch travels deep to the tendon of the sternothyroid muscle and innervates the cricothyroid muscle.

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

The recurrent laryngeal nerve is the primary motor nerve of the larynx. After the vagus nerve enters the thoracic cavity, it gives rise to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. On the left side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve loops around the arch of the aorta, while on the right side, it loops around the subclavian artery. The nerve then ascends within the tracheoesophageal groove deep to the thyroid gland, giving off several small branches to innervate the mucosa of the cervical trachea and esophagus. The main trunk enters the larynx posterior to the cricothyroid joint. It innervates all intrinsic laryngeal muscles except the cricothyroid muscle and also contains sensory fibers that supply the mucosa of the subglottic region.

Anatomical Characteristics of the Pediatric Larynx

The anatomy of the pediatric larynx differs from that of adults, with the following key features:

The submucosal tissue in the pediatric larynx is relatively loose, which makes it prone to swelling during inflammation. Because the laryngeal cavity, especially the glottic region, is particularly narrow in children, acute laryngitis in infants and children can easily lead to laryngeal obstruction and result in respiratory distress.

The larynx in children is positioned higher compared to adults. In infants around 3 months old, the arch of the cricoid cartilage is located at the level of the inferior margin of the fourth cervical vertebra. By 6 years of age, it descends to the level of the fifth cervical vertebra.

The laryngeal cartilages in children are not yet calcified and are softer compared to those in adults. During palpation of the thyroid and cricoid cartilages in children, the tactile sensation is less distinct compared to adults.