Routine examination of the pharynx is essential when diagnosing diseases across various clinical disciplines. However, from the perspective of the otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery specialty, specific requirements exist for the scope and details of pharyngeal examination. A thorough medical history is typically collected before the examination begins. Visual inspection involves observing the patient's facial expression, demeanor, and overall condition. Each section of the pharynx, including the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and laryngopharynx, is examined in turn, and imaging studies may be used when necessary.

Examination of the Oropharynx

The patient sits upright, relaxed, with the mouth naturally open. A tongue depressor is used to lightly press on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue to observe the oropharyngeal mucosa for signs of congestion, ulceration, or lesions. The soft palate is examined for sagging or clefts, and the symmetrical movement of both sides is evaluated. The uvula is assessed for elongation or bifurcation. The bilateral palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches are checked for redness, swelling, or ulceration. Each tonsil is inspected for size, congestion, exudates, pseudomembrane, scarring on the surface, or the presence of caseous material in the crypts. The posterior pharyngeal wall is examined for lymphoid follicle hyperplasia, swelling, or protrusions. Pharyngeal palpation can provide information about the size, texture, range, and mobility of masses located in the posterior or parapharyngeal areas.

Examination of the Nasopharynx

Indirect Nasopharyngoscopy

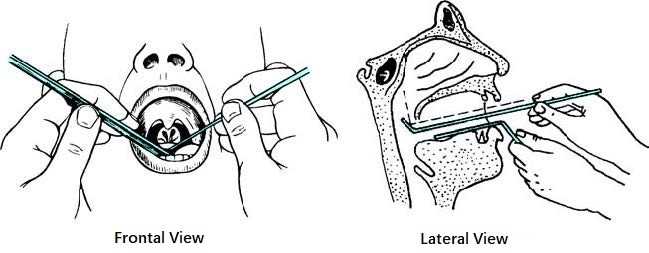

This is a common and straightforward method. In individuals with a sensitive pharyngeal reflex, a 1% tetracaine spray may be used to anesthetize the pharyngeal mucosa. The patient sits upright, keeps their mouth open, and breathes through the nose to relax the soft palate. The examiner uses the left hand to hold a tongue depressor, pressing the anterior two-thirds of the tongue downward, and the right hand to hold an indirect nasopharyngoscope (also called a posterior rhinoscope) that has been pre-warmed but not overheated. The mirror surface is directed upward and inserted into the oral cavity on one side, positioned between the soft palate and the posterior pharyngeal wall without contacting surrounding tissues to prevent the pharyngeal reflex. The mirror angle is adjusted to sequentially visualize the walls of the nasopharynx, including the posterior surface of the soft palate, posterior edge of the nasal septum, choanae, pharyngeal opening of the auditory tube, torus tubarius, pharyngeal recess, and adenoid tissue. The nasopharyngeal mucosa is assessed for signs of congestion, roughness, bleeding, ulceration, secretions, protrusions, or lesions.

Figure 1 Indirect nasopharyngoscopy

Nasopharyngeal Endoscopy

Two types of endoscopes are used: rigid and flexible endoscopes. The rigid endoscope can be introduced through the oral or nasal cavity, while the flexible endoscope, made of bendable fiberoptic material, is introduced through the nasal cavity and allows for adjustable angles to comprehensively observe the nasopharynx, oropharynx, laryngopharynx, and larynx. Electronic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy, an advancement of fiberoptic endoscopy, provides higher image clarity and can integrate with photography and video recording systems to display and archive findings for consultations and teaching. Narrow band imaging (NBI) technology, incorporated into electronic endoscopy, utilizes filters to exclude broadband spectra, leaving only narrow bands of blue and green light. This method is useful for assessing masses in the nasopharynx and pharynx and provides preliminary vascular morphology-based assessments of tumor malignancy.

Nasopharyngeal Palpation

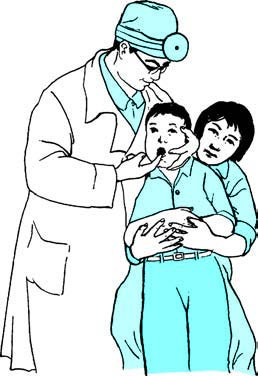

Previously common for children, this method is now rarely used. The child is immobilized by an assistant. The examiner stands behind the child on the right side, using the left index finger to firmly press the child’s cheek. The gloved right index finger is then introduced into the nasopharynx via the oral cavity to palpate its walls. The examiner evaluates for signs of choanal atresia and the size of any adenoid tissue. In the presence of masses, size, texture, and their relationship to surrounding structures are noted. Upon withdrawing the finger, any pus or blood traces on the fingertip are inspected. This procedure can be uncomfortable and should be explained to the patient or the child’s parents. The operation is performed swiftly, accurately, and gently.

Figure 2 Position for nasopharyngeal palpation in children

Figure 3 Diagram indicating the position for nasopharyngeal palpation

Examination of the Laryngopharynx

The primary methods include indirect laryngoscopy and electronic or fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Details can be found in the relevant sections of laryngeal examination protocols discussed in the fifth chapter on laryngology.

Imaging Studies of the Pharynx

Routine clinical and endoscopic examinations are limited to detecting surface lesions of the pharynx. Diagnosing deeper structural abnormalities, such as those in the lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls, requires imaging studies. Examples include lateral X-rays of the neck and skull base. However, conventional X-rays and computed tomography (CT) scans offer limited diagnostic value for soft tissues due to poor resolution. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are now commonly used, offering high-resolution images of both skeletal and soft tissue structures, thus improving the diagnostic accuracy for pharyngeal lesions. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) can be employed to determine the extent and metastasis of malignant tumors in the pharynx.