The pharynx is the shared upper pathway of the respiratory and digestive tracts. It is a funnel-shaped structure that is broad at the top and narrows inferiorly, with a flattened anterior-posterior orientation. It begins at the base of the skull and extends down to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage (approximately the level of the sixth cervical vertebra), measuring roughly 12 cm in length in adults. Anteriorly, it communicates with the nasal cavity, oral cavity, and laryngeal cavity. Posteriorly, it is adjacent to the prevertebral fascia, while its lateral walls are near major blood vessels and nerves in the neck.

Divisions of the Pharynx

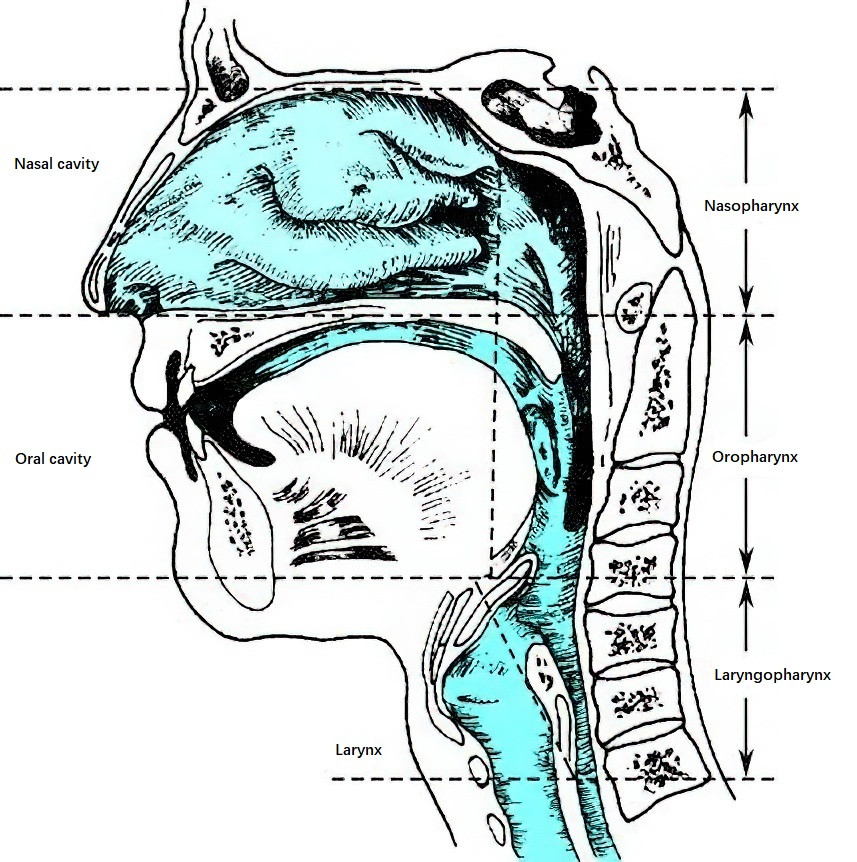

The pharynx is divided into three parts—nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx—separated by the plane of the soft palate and the plane of the upper border of the epiglottis.

Figure 1 Sections of the pharynx

Nasopharynx (Epipharynx)

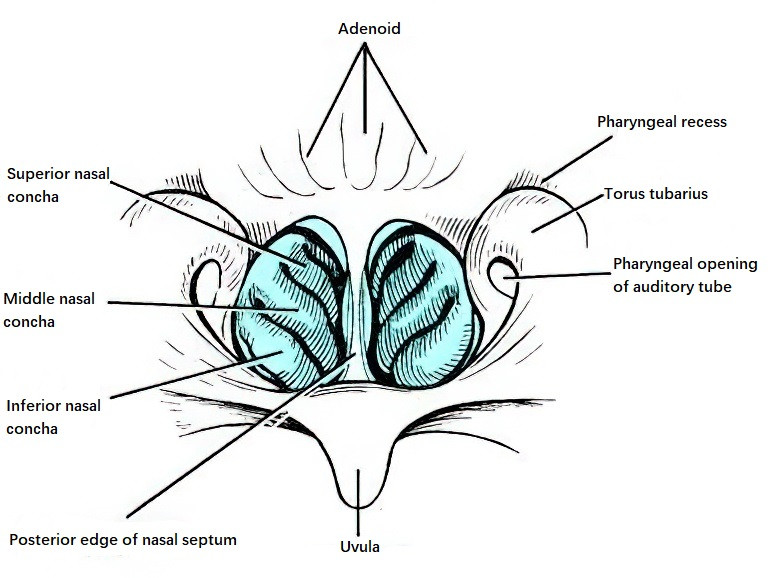

The nasopharynx is the uppermost part of the pharynx, located between the base of the skull and the plane of the soft palate. Anteriorly, its central portion corresponds to the posterior edge of the nasal septum, with the lateral walls forming the choanae that connect it to the nasal cavity. The roof is formed by the body of the sphenoid bone and the basilar portion of the occipital bone. Its posterior wall corresponds roughly to the first and second cervical vertebrae. Together, the roof and posterior wall form a dome-shaped area called the pharyngeal fornix. Beneath its mucosa lies an abundance of lymphoid tissue called the adenoid, or pharyngeal tonsil.

Figure 2 Nasopharynx

On each lateral wall, the nasopharynx contains several key anatomical structures, including the pharyngeal opening of the auditory (Eustachian) tube, the tubal tonsil, the torus tubarius, and the pharyngeal recess. The pharyngeal opening of the auditory tube is located 1.0–1.5 cm posterior to the posterior end of the inferior nasal concha and has a roughly triangular or trumpet-like shape. Scattered lymphatic tissue around the opening forms the tubal tonsil. The torus tubarius is the bulging area superior to the opening, while the area between the posterior-superior aspect of the torus tubarius and the posterior pharyngeal wall is called the pharyngeal recess. The pharyngeal recess is adjacent to the foramen lacerum at the base of the skull and is a common site for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Inferiorly, the nasopharynx communicates with the oropharynx through the nasopharyngeal isthmus, which is formed by the posterior surface and edge of the soft palate together with the posterior pharyngeal wall. During swallowing, the soft palate elevates to contact the posterior pharyngeal wall, temporarily closing the nasopharyngeal isthmus and separating the nasopharynx from the oropharynx.

Oropharynx (Mesopharynx)

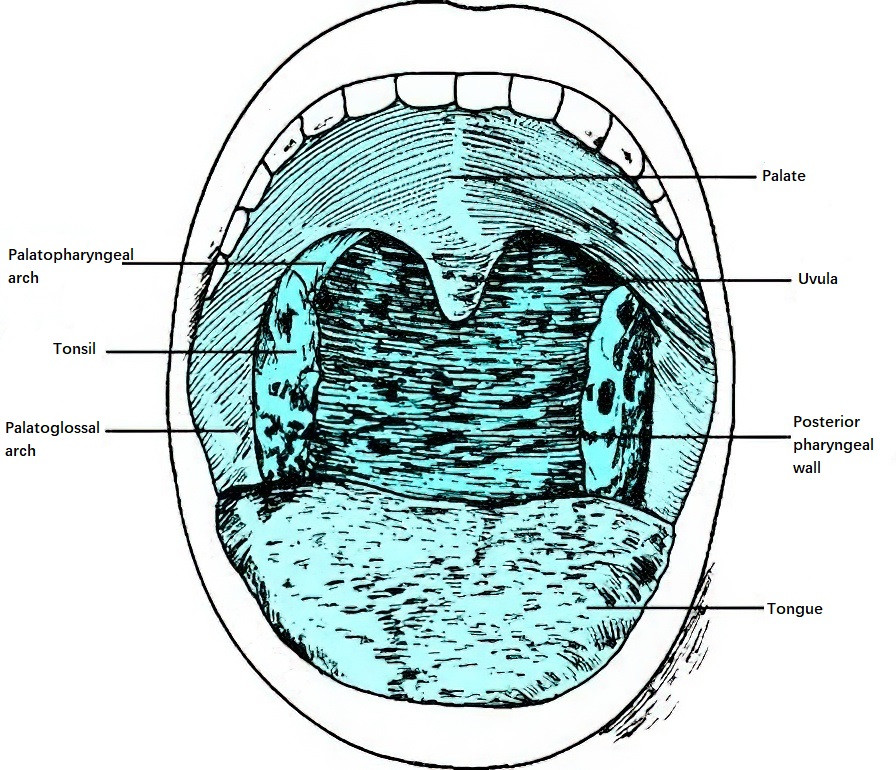

The oropharynx is the middle segment of the pharynx, serving as the posterior continuation of the oral cavity. It is located between the plane of the soft palate and the plane of the upper border of the epiglottis. This region is commonly referred to as the "throat." Its posterior wall corresponds to the second and third cervical vertebrae. Lymphatic follicles are scattered beneath the mucosa.

Figure 3 Oropharynx

The oropharynx communicates anteriorly with the oral cavity through the isthmus of the fauces. The isthmus is an annular narrowing formed by the uvula and the free margin of the soft palate above, the tongue dorsum below, and the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches on either side. The soft palate divides into two arches: the anterior palatoglossal arch (glossopalatine arch) and the posterior palatopharyngeal arch (pharyngopalatine arch). Between these two arches lies the tonsillar fossa, which houses the palatine tonsil. Posterior to the palatopharyngeal arch on each side are vertical lymphoid ridges called the lateral pharyngeal bands.

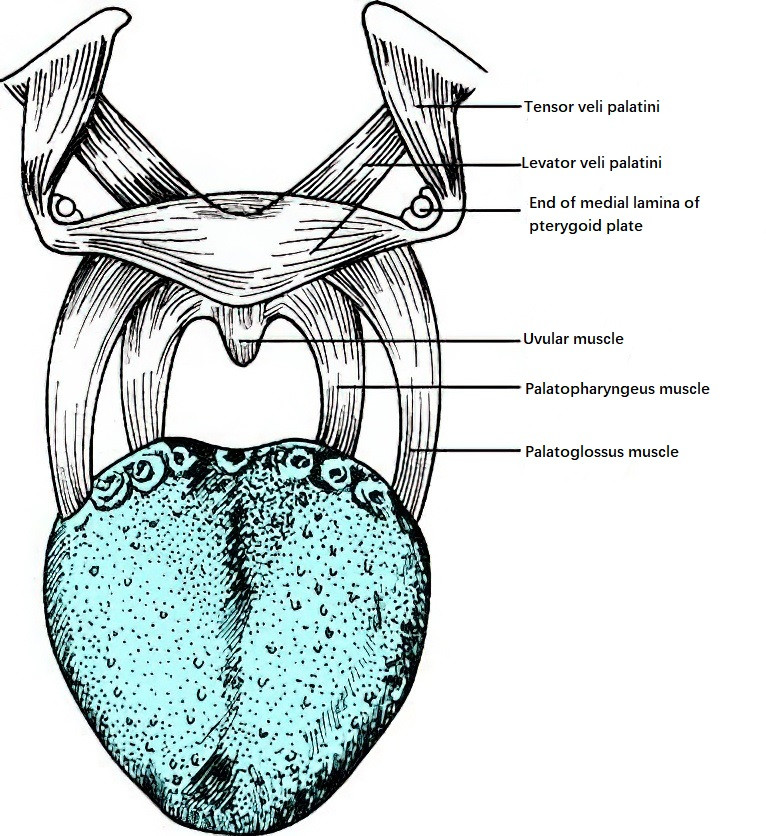

The roof of the oral cavity is called the palate. Its anterior two-thirds form the hard palate, which is composed of the palatine processes of the maxillae and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones. The posterior one-third is the soft palate, composed of muscles including the tensor veli palatini, levator veli palatini, palatoglossal muscle, palatopharyngeal muscle, and the uvular muscle. Inferiorly, the floor of the mouth is formed by the tongue and the muscles of the oral cavity base. The tongue is a muscular structure with a rough, stratified squamous epithelial surface closely connected to the underlying muscle. At its posterior end, the foramen cecum marks the vestigial site of the embryonic thyroglossal duct. The posterior third of the tongue contains lymphoid tissue known as the lingual tonsil. The mucosal fold on the underside of the tongue connecting it to the floor of the mouth is called the frenulum of the tongue. On either side of the frenulum are the openings of the submandibular ducts.

Laryngopharynx (Hypopharynx)

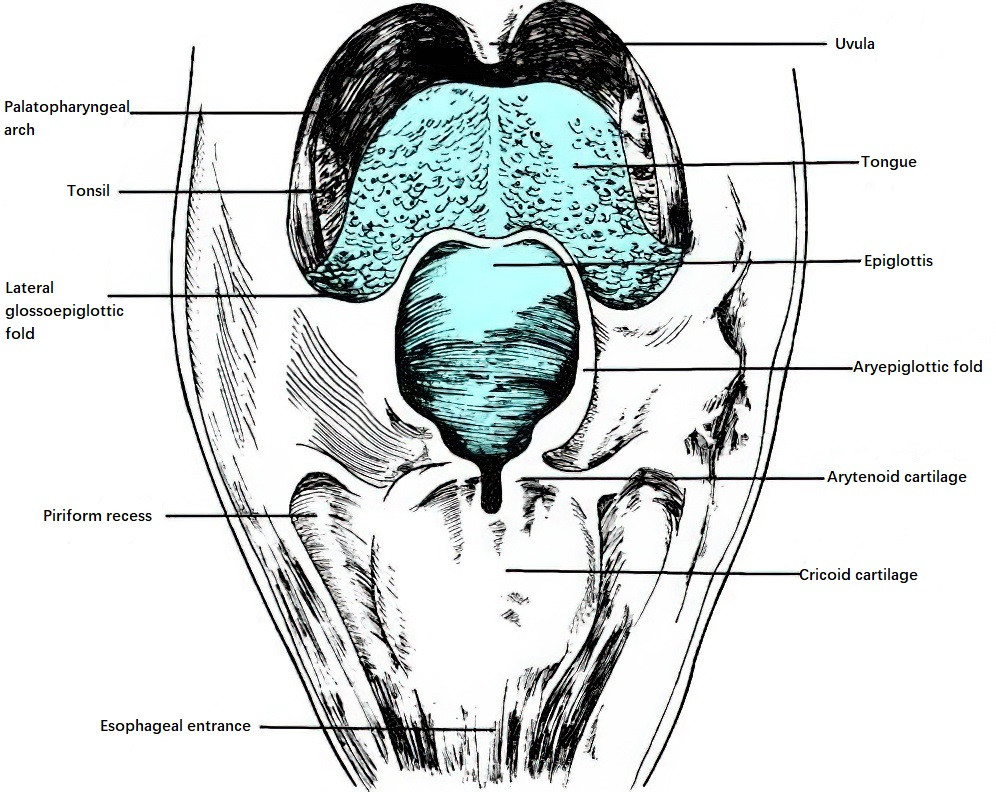

The laryngopharynx, or hypopharynx, is the lowest portion of the pharynx, extending between the plane of the upper border of the epiglottis and the lower border of the cricoid cartilage, where it continues into the esophagus. Its posterior wall corresponds to the third through sixth cervical vertebrae.

Figure 4 Laryngopharynx

Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx contains the laryngeal inlet (aditus of the larynx), which is surrounded superiorly by the epiglottis, laterally by the aryepiglottic folds, and inferiorly by the arytenoid cartilages. Between the root of the tongue and the epiglottis lies the median glossoepiglottic fold, a central sagittal mucosal fold flanked on either side by two shallow depressions called the valleculae. These depressions often serve as locations where foreign bodies can become lodged. Lateral to each vallecula is the lateral glossoepiglottic fold, which connects the tongue root to the lateral margins of the epiglottis.

On either side of the laryngeal inlet lies the piriform sinus, a deeper recess that serves as a pathway for food and liquid. The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve passes through the piriform sinus and supplies the underlying mucosa. The space between the posterior aspect of the cricoid cartilage plate and the posterior pharyngeal wall is called the postcricoid space. Inferior to this lies the entrance to the esophagus, surrounded by the cricopharyngeal muscle.

Structure of the Pharyngeal Wall

Layers of the Pharyngeal Wall

The pharyngeal wall consists of four layers from inside outward: the mucosal layer, fibrous layer, muscular layer, and external membrane layer. A notable feature of the pharyngeal wall is the absence of a distinct submucosal layer, with the fibrous layer closely adhering to the mucosal layer.

Mucosal Layer

The mucosa of the pharynx is continuous with that of the auditory (Eustachian) tube, nasal cavity, oral cavity, and larynx. Due to different functions, the mucosa in the nasopharynx is primarily pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium containing goblet cells, with mixed glands in its lamina propria. The mucosa of the oropharynx and laryngopharynx consists of stratified squamous epithelium. Beneath the mucosa, in addition to abundant mucous and serous glands, there is a substantial aggregation of lymphoid tissue that, together with other lymphatic structures of the pharynx, forms the pharyngeal lymphatic ring.

Fibrous Layer

Also known as the pharyngobasilar fascia, this layer is primarily composed of the cranial pharyngeal fascia and is located between the mucosal and muscular layers. It is thicker at the cranial base and gradually becomes thinner toward the lower portions. On either side, the fibrous tissue meets at the midline of the posterior wall to form the pharyngeal raphe, which serves as the attachment site for the pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

Muscular Layer

The muscular layer comprises three groups based on function: three pairs of transverse pharyngeal constrictor muscles, three pairs of longitudinal pharyngeal elevator muscles, and five groups of palate-related muscles.

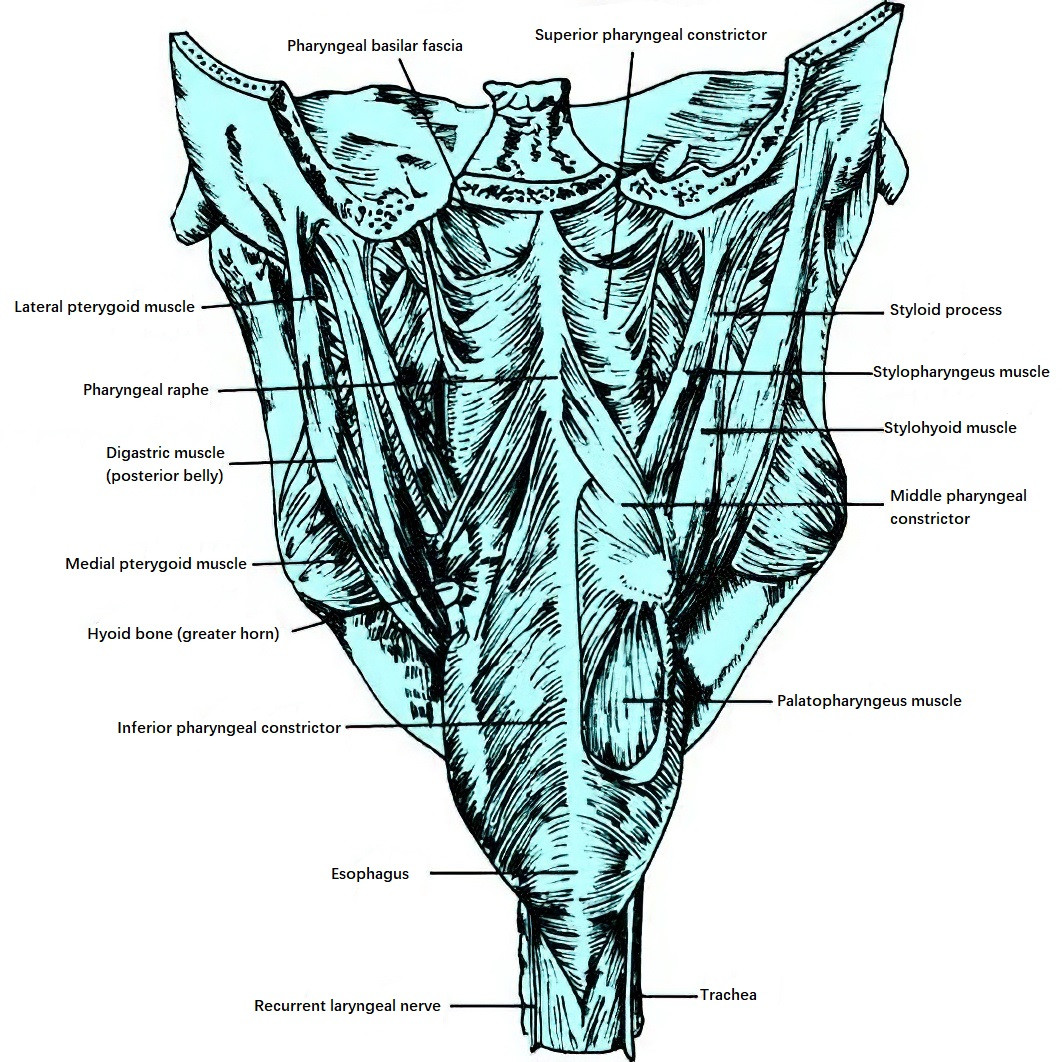

Figure 5 Posterior view of pharyngeal muscles

Pharyngeal Constrictor Muscle Group

This includes the superior, middle, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles. These muscles are obliquely arranged in a shingle-like pattern, wrapping around the sides and posterior wall of the pharynx. Their fibers meet in the posterior midline at the pharyngeal raphe. When the constrictor muscles contract collectively, they reduce the size of the pharyngeal cavity. Sequential contraction of the constrictor muscles during swallowing propels food into the esophagus.

Pharyngeal Elevator Muscle Group

This includes the stylopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus muscles. These longitudinal muscles are situated on the inner surface of the constrictor muscles, descending close to the fibrous layer, and gradually dispersing into the pharyngeal wall. Their contraction elevates the pharynx and larynx, relaxes the pharyngeal walls, seals the laryngeal inlet, and opens the piriform sinuses, enabling food to bypass the epiglottis and enter the esophagus, thereby assisting the swallowing process.

Palatal Muscle Group

This includes the levator veli palatini, tensor veli palatini, palatoglossus, palatopharyngeus, and uvular muscles. This group functions in elevating the soft palate, regulating the opening and closing of the nasopharyngeal isthmus, separating the nasopharynx and oropharynx, and opening the pharyngeal orifice of the auditory tube.

Figure 6 Schematic representation of the palatal muscle group

External Membrane Layer

Also called the fascia layer, this outermost layer covers the pharyngeal constrictor muscles. Composed of connective tissue surrounding the muscular layer, it is an extension of the buccopharyngeal fascia. It is thinner at the top and thicker in the lower regions.

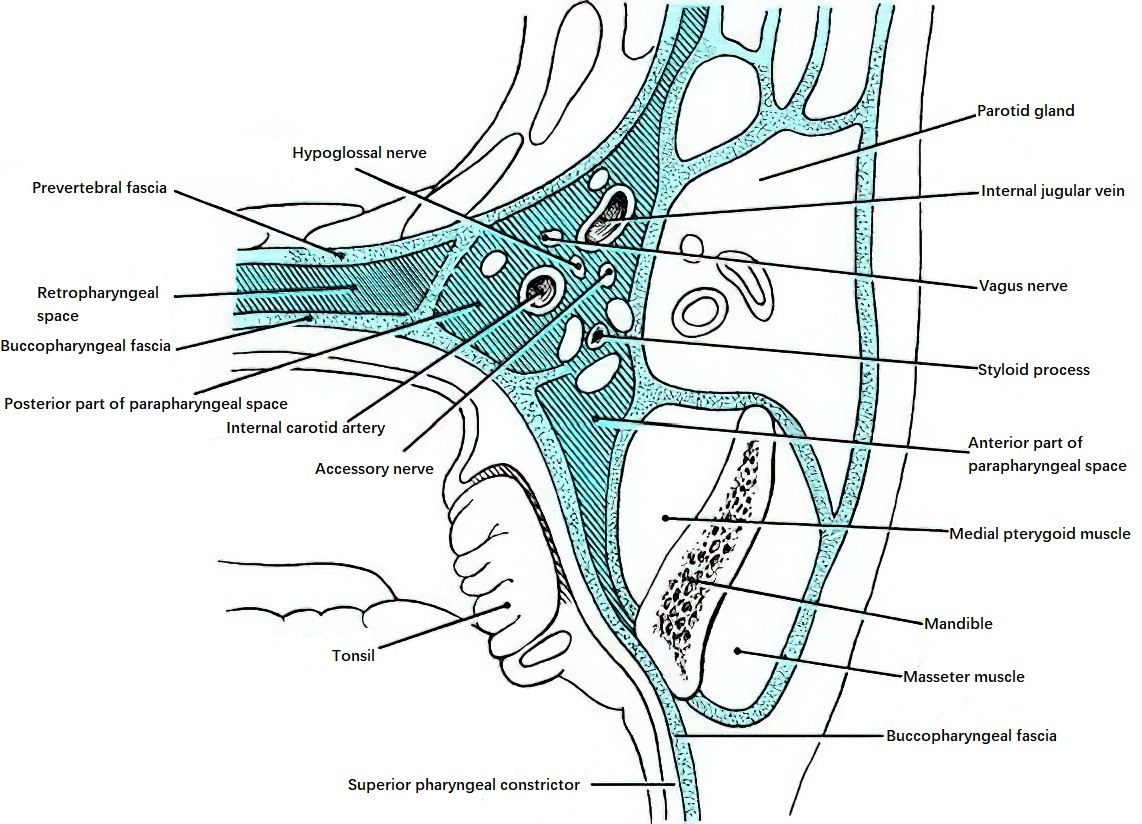

Fascial Spaces

The loose connective tissue spaces between the pharyngeal fascia and adjacent fascia are significant and include the retropharyngeal space and parapharyngeal space. These spaces facilitate pharyngeal movement during swallowing, allow coordinated movement of the head and neck, and contribute to normal physiological function. While these fascial spaces can localize certain pathological processes, they may also serve as pathways for disease spread.

Figure 7 Fascial spaces of the pharynx

Retropharyngeal Space

The retropharyngeal space is located behind the posterior wall of the pharynx, between the prevertebral fascia and the buccopharyngeal fascia. It extends from the cranial base superiorly to the superior mediastinum inferiorly and corresponds approximately to the levels of the first and second thoracic vertebrae. At the midline, the pharyngeal raphe divides this space into left and right compartments, which do not communicate with each other. Loose connective tissue and lymphatic tissue are found within this space, and bilaterally it communicates with the parapharyngeal spaces. In infants and young children, the retropharyngeal space contains numerous lymph nodes, which gradually atrophy during childhood and are sparse in adults. Lymphatic drainage from the tonsils, oral cavity, posterior nasal cavity, nasopharynx, auditory tube, and tympanic cavity passes through this space.

Parapharyngeal Space

The parapharyngeal space, also known as the lateral pharyngeal space or pharyngomaxillary space, lies between the lateral pharyngeal wall (superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle) and the fascia of the medial pterygoid muscle. It is separated from the retropharyngeal space by only a thin layer of fascia. Each of these spaces, one on each side, resembles a cone shape, with the base pointing superiorly toward the cranial base and the apex directed inferiorly toward the hyoid bone. Medially, it is adjacent to the buccopharyngeal fascia and pharyngeal constrictor muscle, in proximity to the tonsils. Laterally, it is bordered by the ramus of the mandible, the deep surface of the parotid gland, and the medial pterygoid muscle. Posteriorly, it is bordered by the prevertebral fascia.

The parapharyngeal space is further divided into an anterior compartment (muscular or prestyloid compartment) and a posterior compartment (neurovascular or retrostyloid compartment) by the styloid process and its associated muscles. The anterior compartment is smaller and contains the external carotid artery and venous plexus. Medially, it is adjacent to the tonsil, while laterally, it is closely associated with the medial pterygoid muscle. The posterior compartment is larger and contains the internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, hypoglossal nerve, accessory nerve, sympathetic trunk, and cervical deep lymph nodes. The parapharyngeal space communicates anteroinferiorly with the submandibular space, medially and posteriorly with the retropharyngeal space, and laterally with the masticator space.

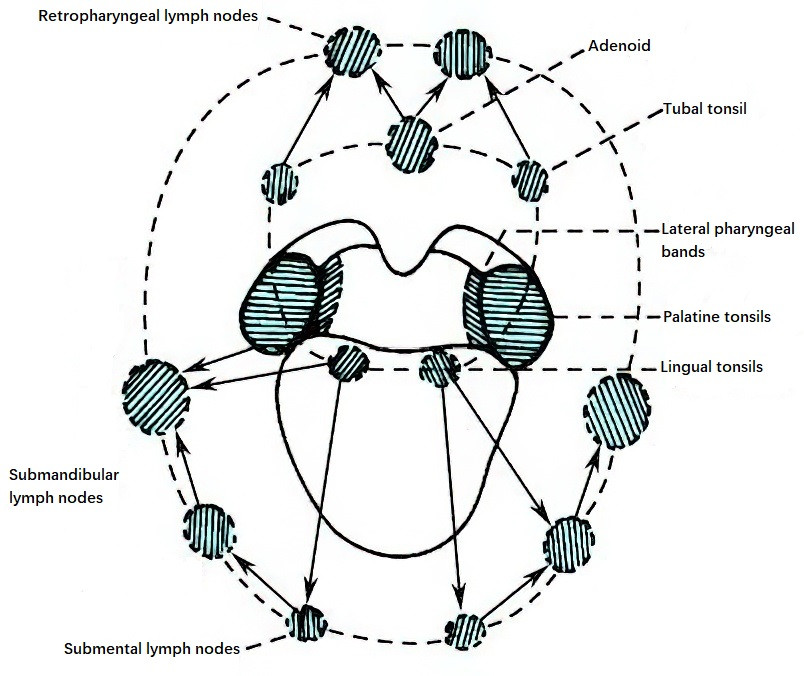

Lymphatic Tissue of the Pharynx

The submucosal layer of the pharynx contains abundant lymphatic tissue, with larger lymphatic aggregates forming a circular arrangement known as the pharyngeal lymphatic ring (Waldeyer’s ring). The inner ring primarily consists of the pharyngeal tonsil (adenoid), tubal tonsils, palatine tonsils, lateral pharyngeal bands, lymphatic follicles of the posterior pharyngeal wall, and lingual tonsils. The lymph from the inner ring drains into cervical lymph nodes, which communicate with one another to form an outer ring. The outer ring primarily includes the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, submandibular lymph nodes, and submental lymph nodes. All lymphatic drainage from the pharynx flows into the deep cervical lymph nodes. Lymph from the nasopharynx first flows into the retropharyngeal lymph nodes and then enters the upper deep cervical lymph nodes. In the oropharynx, lymph primarily drains into the submandibular lymph nodes, while lymph from the laryngopharynx passes through the thyrohyoid membrane to reach the lymph nodes near the internal jugular vein (middle group).

Figure 8 Schematic representation of the pharyngeal lymphatic ring

Pharyngeal Tonsil (Adenoid)

The pharyngeal tonsil is located at the junction of the roof and the posterior wall of the nasopharynx. It resembles half a peeled orange, with an uneven surface featuring 5–6 longitudinal grooves, the deepest of which forms a central recess. Occasionally, a remnant depression from the embryonic period, known as the pharyngeal bursa, can be observed at the lower end of this recess. The adenoid is present at birth and becomes most prominent around 6–7 years of age but generally undergoes gradual atrophy after the age of 10.

Palatine Tonsil

Commonly referred to as "tonsils," the palatine tonsils are located on either side of the oropharynx within the triangular tonsillar fossa formed by the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches. These are the largest lymphatic tissues in the pharyngeal region. Lymphatic tissue proliferates around 6–7 years of age, leading to physiological hypertrophy, but the tonsils gradually atrophy beyond middle age.

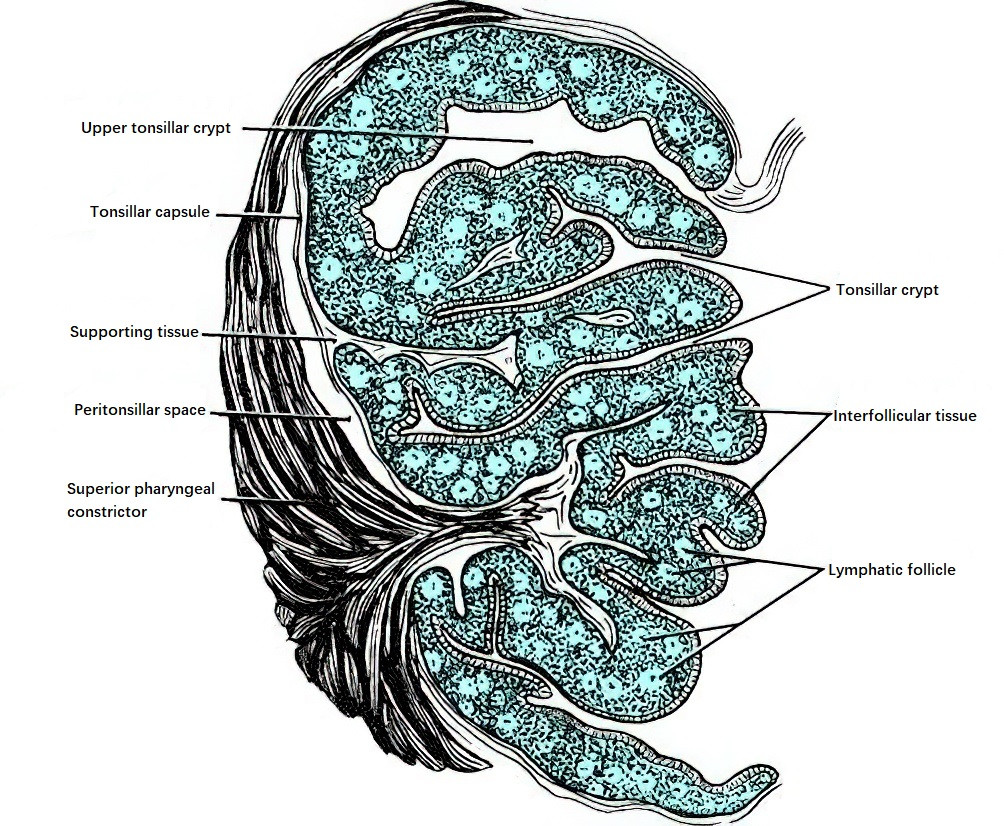

Structure of the Palatine Tonsil

The palatine tonsil is a pair of flattened, oval-shaped lymphoepithelial organs. It has a medial (free) surface, a lateral (deep) surface, an upper pole, and a lower pole. All parts except for the medial surface are enclosed in a connective tissue capsule. Its lateral surface is adjacent to the pharyngeal fascia and the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle. Loose connective tissue between the pharyngeal fascia and tonsillar capsule forms a potential space called the peritonsillar space.

Figure 9 Coronal section of the palatine tonsil

The medial surface faces the pharyngeal cavity and is covered with squamous epithelial mucosa. The epithelium invaginates into the tonsillar parenchyma, forming 6–20 crypts of varying depths, known as tonsillar crypts. The upper and lower poles of the tonsil are connected by mucosal folds. The upper fold, called the semilunar fold, is located at the intersection of the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches, while the lower fold, called the triangular fold, extends downward from the palatoglossal arch and wraps around the anteroinferior part of the tonsil. The tonsils consist of lymphoid tissue rich in a connective tissue framework and interfollicular lymphatic tissue. Connective tissue from the capsule extends into the tonsil, forming trabeculae that serve as a scaffold. Numerous lymphatic follicles, each with a germinal center, are present between the trabeculae. Interfollicular spaces are filled with developing lymphocytes.

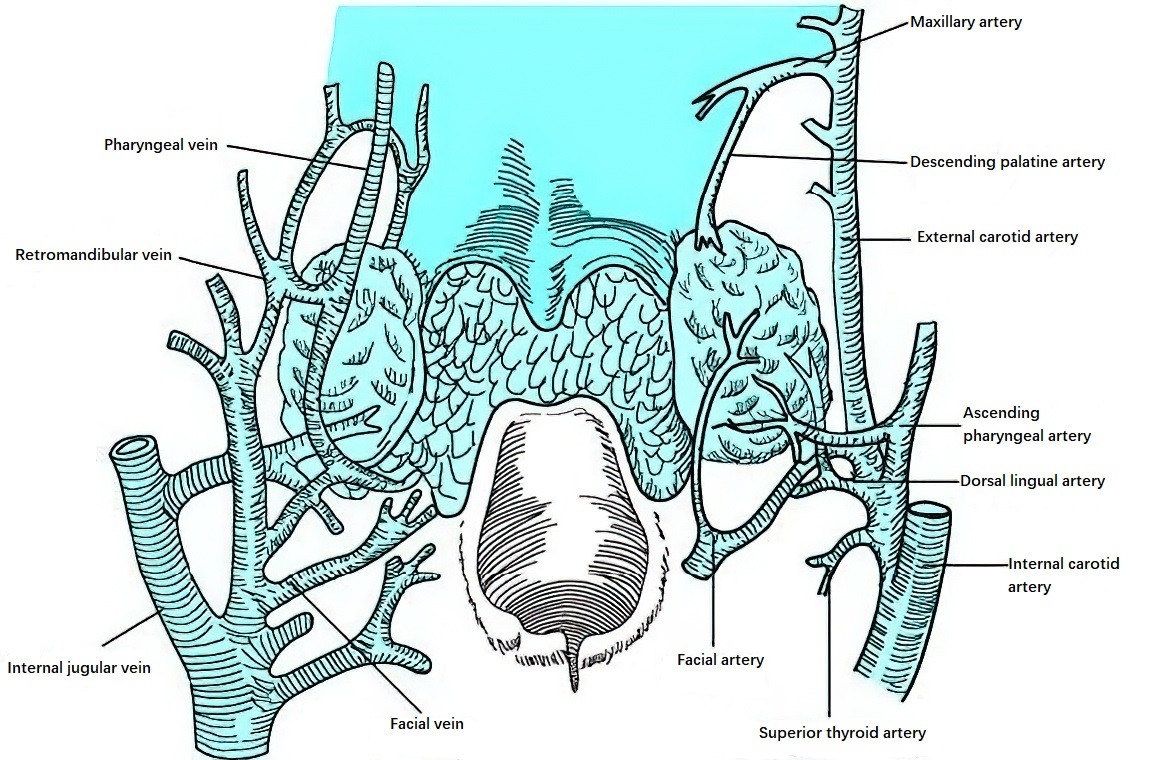

Blood Supply of the Palatine Tonsil

The palatine tonsils are highly vascularized, receiving arterial blood from five branches of the external carotid artery:

- Descending palatine artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, supplies the upper pole and soft palate.

- Ascending palatine artery, a branch of the facial artery.

- Tonsillar branch of the facial artery.

- Tonsillar branch of the ascending pharyngeal artery.

- Dorsal lingual artery, arising from the lingual artery, primarily supplies the lower pole of the tonsil.

The first four arteries supply the tonsil and the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches.

Figure 10 Vascular distribution of the tonsil

The tonsillar branch of the facial artery, which mainly supplies the tonsillar parenchyma, is the primary arterial source. Venous drainage from the tonsil flows into the surrounding peritonsillar venous plexus outside the tonsillar capsule and then into the pharyngeal venous plexus and lingual vein, eventually draining into the internal jugular vein.

Innervation of the Palatine Tonsil

The palatine tonsils are innervated by the pharyngeal plexus, the second branch of the trigeminal nerve (maxillary nerve), and branches of the glossopharyngeal nerve.

Lingual Tonsil

The lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue and has a granular appearance, with size varying among individuals. It contains abundant mucous glands as well as short, narrow crypts. These crypts, along with surrounding lymphatic tissue, form lymphatic follicles that constitute the lingual tonsil.

Tubal Tonsils

Tubal tonsils consist of lymphatic tissue located at the posterior margin of the pharyngeal opening of the auditory tube. Inflammation of this region may obstruct the auditory tube, resulting in hearing loss or middle ear infections.

Lateral Pharyngeal Bands

Lymphatic tissue extends vertically along the lateral walls of the pharynx and is located posterior to the palatopharyngeal arch. It extends from the oropharynx upward to the nasopharynx, connecting with the lymphatic tissue of the pharyngeal recess.

Vasculature and Innervation of the Pharynx

Arteries

Arterial blood supply to the pharynx is derived from branches of the external carotid artery, including the ascending pharyngeal artery, superior thyroid artery, ascending palatine artery, descending palatine artery, and dorsal lingual artery.

Veins

Venous blood from the pharynx flows through the pharyngeal venous plexus and the pterygoid venous plexus, eventually draining into the facial vein and internal jugular vein.

Nerves

The pharyngeal nerve supply originates from the pharyngeal plexus, which includes contributions from the glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, and cervical sympathetic trunk (superior cervical ganglion). These nerves mediate sensation and control the motor function of pharyngeal muscles. The tensor veli palatini is innervated by the mandibular nerve (the third branch of the trigeminal nerve). The mucosa of the upper part of the nasopharynx is supplied by the maxillary nerve (the second branch of the trigeminal nerve).