The facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) is the cranial nerve with the longest course within a bony canal. It originates from the motor nucleus of the facial nerve and innervates ipsilateral facial expression muscles, the lacrimal gland, salivary glands, and other target organs. The motor nucleus of the facial nerve receives input primarily from the cortical center of the facial nerve located in the lower precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. Part of the motor nucleus is supplied by corticospinal fibers originating from the contralateral motor cortex, and the motor fibers from this portion innervate the lower facial muscles on the same side. Meanwhile, another portion of the motor nucleus is supplied by corticospinal fibers from both hemispheres, and the fibers arising from this portion innervate the frontalis, orbicularis oculi, and corrugator supercilii muscles. This anatomical arrangement explains why lesions above the facial nerve nucleus that involve the connection between the nucleus and the cerebral cortex result in paralysis of the contralateral lower facial muscles, while forehead wrinkling and eye closure remain unaffected. This distinction is a crucial diagnostic criterion for differentiating between central and peripheral facial paralysis.

Composition of the Facial Nerve and the Functions of Its Fibers

The facial nerve is a mixed nerve that contains motor, parasympathetic, taste-related, and sensory fiber components, with the majority being motor fibers and the remaining being sensory and parasympathetic fibers.

Motor Fibers

The motor fibers of the facial nerve innervate nearly all of the facial expression muscles, as well as the stapedius muscle, stylohyoid muscle, and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. The motor center of the facial nerve is connected to the motor nucleus of the facial nerve through three distinct conduction pathways:

Crossed Pyramidal Tract

This tract originates from the contralateral cortical center and terminates in the motor nucleus of the facial nerve, controlling all facial muscle movements on the same side. Lesions in the central nervous system on one side result in facial paralysis on the contralateral side.

Uncrossed Pyramidal Tract

Some fibers from the ipsilateral cortical center contribute to this tract and terminate in the motor nucleus, controlling the movements of muscles above the eyes, such as the frontalis, orbicularis oculi, and corrugator supercilii muscles.

Extrapyramidal Tract

This tract transmits neural signals from the emotional centers, which may be located in regions such as the thalamus, striatum, and substantia nigra, to the muscles of facial expression. The motor nucleus of the facial nerve is also connected to the trigeminal nerve, optic nerve, and vestibulocochlear nerve, enabling reflex contractions of certain muscles. Among these reflexes, two are notably significant:

Blink Reflex

This occurs in response to tactile, visual, or auditory stimuli.

Stapedius Reflex

This occurs when the stapedius muscle contracts in response to auditory stimuli of sufficient intensity.

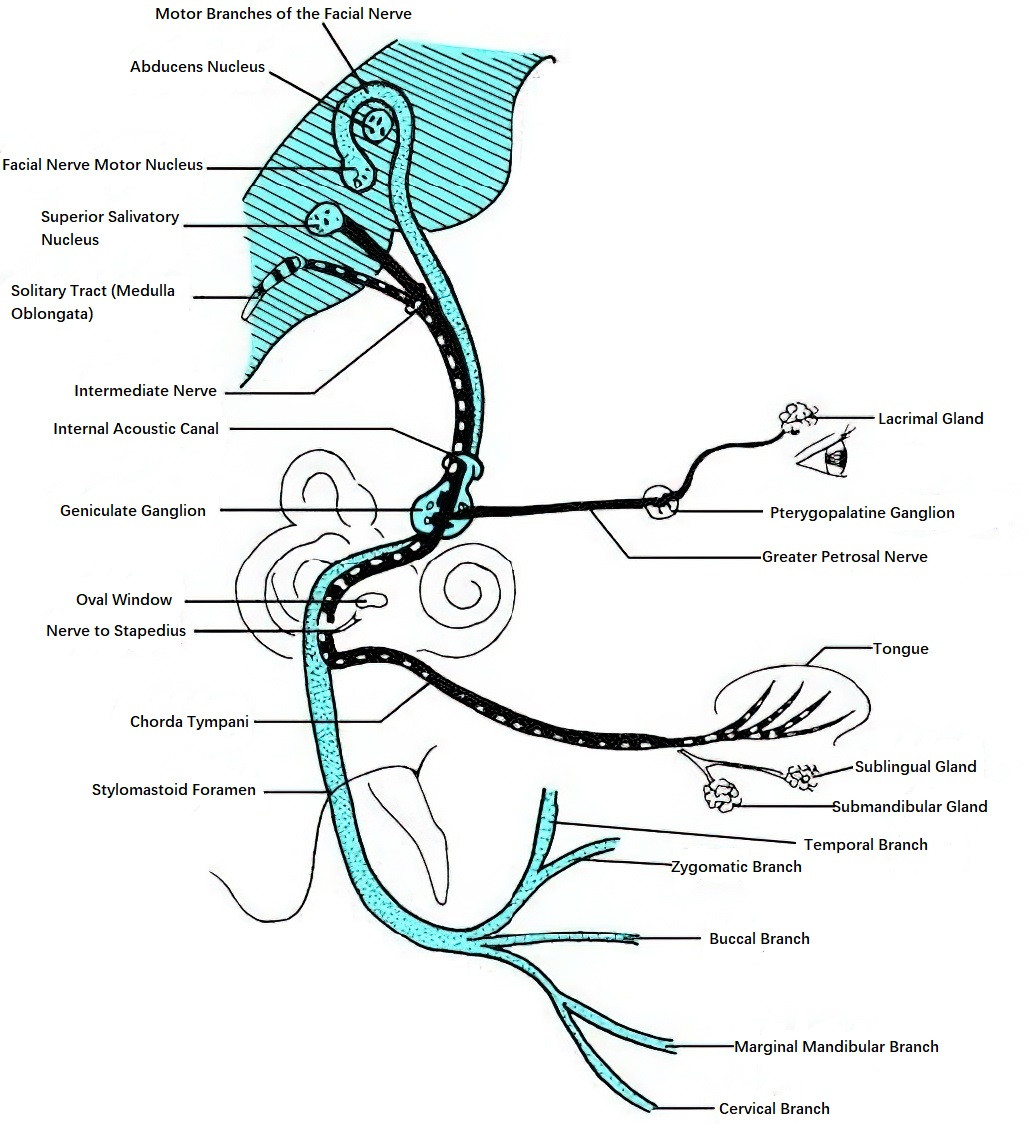

Parasympathetic Fibers

The parasympathetic fibers of the facial nerve are responsible for the secretion of the lacrimal glands, nasal mucosal glands, submandibular glands, and sublingual glands. These fibers originate from the superior salivatory nucleus in the rostral part of the brainstem, exit the brainstem along with the motor fibers of the facial nerve at the lower part of the pons, and run between the motor fibers and the vestibulocochlear nerve. This parasympathetic component is also referred to as the intermediate nerve. After entering the internal acoustic meatus, the intermediate nerve merges with the motor fibers to form the main trunk of the facial nerve, passing through the geniculate ganglion. Some fibers travel to the pterygopalatine ganglion via the greater petrosal nerve, where postganglionic fibers innervate the lacrimal glands, nasal mucosal glands, and nasal vasculature. The remaining fibers travel with the main trunk of the facial nerve through its tympanic and mastoid segments, ultimately reaching the submandibular ganglion via the chorda tympani nerve. Postganglionic fibers innervate the submandibular and sublingual glands, with a small number potentially distributing to accessory salivary glands in the oral cavity.

Taste Fibers

The taste fibers of the facial nerve are responsible for taste sensation in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. These fibers travel through the lingual nerve and the chorda tympani nerve, joining the main trunk of the facial nerve and traveling to the geniculate ganglion. The cell bodies of these fibers are located in the geniculate ganglion. The central axons of these fibers ascend within the intermediate nerve and terminate in the solitary nucleus of the brainstem.

Sensory Fibers

The sensory fibers of the facial nerve are involved in transmitting sensory information from parts of the auricle and external auditory canal. However, the exact conduction pathway of these fibers remains unclear.

Course of the Facial Nerve

The motor fibers of the facial nerve arise from the motor nucleus of the facial nerve, first looping around the abducens nucleus and exiting from the lower margin of the pons. They extend outward, passing over the cerebellopontine angle and accompanying the vestibulocochlear nerve, entering the internal acoustic canal via the internal acoustic meatus. The facial nerve traverses above the transverse crest at the floor of the internal acoustic canal and enters the facial nerve canal anterior to the vertical crest (Bill’s crest). Inside the facial nerve canal, the nerve initially runs outward and slightly forward between the cochlea and the semicircular canals. Upon reaching the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, the nerve turns outward and posteriorly, a segment known as the genu. This genu area of the facial nerve is slightly enlarged and is termed the geniculate ganglion. From the geniculate ganglion, the nerve travels along the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, moving posteriorly and slightly downward, above the cochleariform process and oval window, and below the lateral semicircular canal. Posterior to the pyramidal eminence, the facial nerve takes a vertical course downward and slightly outward, traveling along the bony canal of the posterior wall of the external auditory canal. It eventually exits through the stylomastoid foramen located anterior to the digastric ridge.

The facial nerve's total length within the temporal bone is approximately 30 mm. After exiting the stylomastoid foramen, the main trunk of the facial nerve first gives off the posterior auricular nerve and the digastric branch. The nerve then curves upward and forward to enter the parotid gland, where it divides into two main branches: the temporofacial division and the cervicofacial division. The temporofacial division gives rise to the temporal, zygomatic, and upper buccal branches, while the cervicofacial division gives rise to the lower buccal, mandibular marginal, and cervical branches. Emerging from the anterior border of the parotid gland, these branches interconnect in a plexiform pattern and fan out to innervate the ipsilateral facial expression muscles.

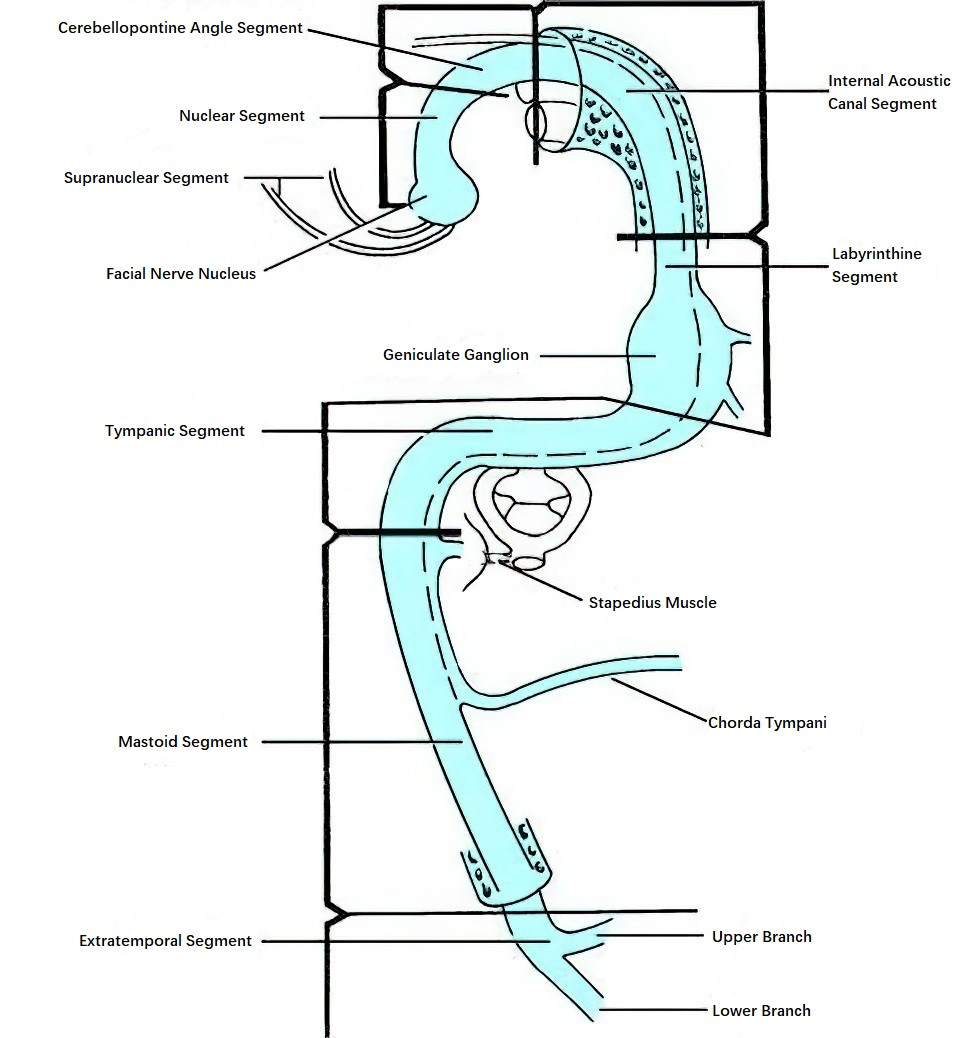

Segmentation of the Facial Nerve

There are various approaches to dividing the facial nerve into segments, but it is commonly divided into eight segments:

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the segments of the facial nerve

Supranuclear Segment

This segment originates from the facial nerve cortical center in the frontal lobe and extends to the motor nucleus of the facial nerve at the lower part of the pons.

Nuclear Segment

This segment refers to the intrapontine course of the facial nerve. Nervous fibers emerge from the motor nucleus of the facial nerve, loop around the abducens nucleus, and exit the lower margin of the pons. In this region, the facial nerve is adjacent to the entry point of the vestibulocochlear nerve into the brainstem, the abducens nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve, the medial wall of the lateral recess of the fourth ventricle, and the cerebellar flocculus.

Cerebellopontine Angle Segment

After leaving the pons, the facial nerve traverses the cerebellopontine angle, accompanying the vestibulocochlear nerve to the internal acoustic meatus. In this segment, the facial nerve lies above the vestibulocochlear nerve. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is typically located either anterior or posterior to the nerve and may even pass between the facial nerve and the vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve. Vasculature loops formed by branches of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery or posterior inferior cerebellar artery may also surround the facial nerve in this region.

Internal Acoustic Canal Segment

This segment begins when the facial nerve enters the internal acoustic canal via the internal acoustic meatus and extends to the fundus of the canal. It is approximately 10 mm in length. Here, the facial nerve is positioned anterosuperior to the vestibulocochlear nerve. The distal part of the internal acoustic canal is divided into upper and lower sections by the transverse crest. The facial nerve and superior vestibular nerve are located in the upper section, with the anterior facial nerve positioned anteriorly and the superior vestibular nerve posteriorly. The lower section contains the cochlear nerve (anteriorly) and the inferior vestibular nerve (posteriorly). The facial nerve is separated from the superior vestibular nerve by Bill’s crest. The segment of the facial nerve from the motor nucleus to the facial canal at the fundus of the internal acoustic canal is also referred to as the intracranial segment.

Labyrinthine Segment

The labyrinthine segment includes the portion of the facial nerve that extends from the fundus of the internal acoustic canal into the facial nerve bony canal up to the geniculate ganglion (including the ganglion itself). This segment is the shortest, measuring approximately 2.5–6.0 mm, and represents the narrowest part of the facial nerve canal. The first branch of the facial nerve, the greater petrosal nerve, arises anteriorly from the geniculate ganglion. Congenital absence of bone surrounding the geniculate ganglion may occur, leaving the ganglion directly exposed beneath the dura mater.

Tympanic Segment

Also known as the horizontal segment, this portion extends posteriorly and outward from the geniculate ganglion to the area superior to the pyramidal eminence. It measures approximately 11 mm. In this segment, the nerve travels through a bony canal along the medial wall of the tympanic cavity, situated above the cochleariform process and oval window and below the lateral (horizontal) semicircular canal. Some researchers refer to the segment extending below the lateral semicircular canal to the pyramidal eminence as the pyramidal segment. The bony canal here is extremely thin or may even be absent (bony dehiscence occurs in approximately 25%–45% of cases), making this segment prone to injury during middle ear and mastoid surgeries that can result in facial nerve paralysis.

Mastoid Segment

Also known as the vertical segment, the mastoid segment extends from the pyramidal eminence to the stylomastoid foramen, with a length of approximately 16 mm in adults. In this segment, the facial nerve runs slightly posteriorly within the bony canal of the posterior wall of the external auditory canal, making it the longest segment of the facial nerve. Its position is deepest in adults, typically located more than 2 cm beneath the surface of the mastoid, but it becomes more superficial as it approaches the stylomastoid foramen. Two branches, the nerve to the stapedius and the chorda tympani, arise from this segment. The nerve to the stapedius emerges at the level of the pyramidal eminence, while the chorda tympani shows significant variability in its origin, arising from the anterior, posterior, or lateral aspects of the facial nerve approximately 6 mm above the stylomastoid foramen.

The section of the facial nerve from the facial canal at the fundus of the internal acoustic canal to the stylomastoid foramen is also referred to as the intratemporal segment of the facial nerve. All middle ear, temporal bone, and lateral skull base surgeries are closely related to this segment, requiring otologists to have a detailed understanding of its anatomical landmarks and localization techniques.

Extratemporal Segment

The extratemporal segment refers to the portion of the facial nerve distal to the stylomastoid foramen. In newborns and young children, the stylomastoid foramen is more superficial, making the facial nerve in this region more susceptible to injury. Before entering the parotid gland, the main trunk of the facial nerve lies subcutaneously approximately 1.5 cm anterior to the mastoid process. At the stylomastoid foramen, the facial nerve gives rise to the posterior auricular nerve and the digastric branch, which innervate the posterior auricular muscles, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the stylohyoid muscle. The nerve then passes through the gap formed by the cartilaginous part of the external auditory canal and the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, crossing the anterior surface of the styloid process, the retromandibular vein, and the external carotid artery, before entering the parotid gland. Within the parotid gland, the facial nerve bifurcates into two trunks: the temporofacial trunk and the cervicofacial trunk.

The temporofacial trunk gives rise to the temporal, zygomatic, and upper buccal branches, while the cervicofacial trunk gives rise to the lower buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches. These branches are interconnected by anastomotic fibers, forming the parotid plexus of the facial nerve.

Temporal Branches

These arise from the temporofacial trunk and ascend to exit the parotid gland at its superior edge near the condylar process of the mandible. They are divided into orbital, frontal, and auricular branches based on their areas of distribution. The orbital branches innervate the orbicularis oculi and corrugator supercilii muscles, the frontal branches innervate the frontalis muscle, and the auricular branches supply the auricle and tragus.

Zygomatic Branches

These arise from the superior or anterior edge of the parotid gland. The branches above the zygomatic arch have a course similar to the temporal branches but are located deeper, while those below the zygomatic arch travel between the masseter muscle and its fascia. The zygomatic branches primarily innervate the levator labii superioris and zygomatic muscles.

Buccal Branches

These emerge from the anterior edge of the parotid gland, traveling within the fascia of the parotid overlying the masseter muscle. Some divisions connect with branches of the zygomatic nerve, forming a network that further gives rise to fibers innervating most of the facial expression muscles in the lower face, such as the orbicularis oris, levator labii superioris, and buccinator muscles.

Marginal Mandibular Branches

These arise from the cervicofacial trunk and exit from the inferior edge of the parotid gland. They travel superficially over the retromandibular vein and across the facial artery, exiting the masseter fascia to form anastomotic connections before innervating the muscles of the lower lip and chin.

Cervical Branches

These arise from the inferior edge of the parotid gland and descend within the gland before emerging superficially at the inferior border. They reach the submandibular triangle, traveling deep to the platysma muscle, which they innervate. These branches also form widespread connections with the great auricular nerve.

Intratemporal Branches of the Facial Nerve

The facial nerve gives rise to three main branches as it traverses the temporal bone:

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of the branches of the facial nerve

Greater Petrosal Nerve

This branch arises from the anterior aspect of the geniculate ganglion and courses forward through the bone to enter the middle cranial fossa. Within the fossa, it travels along the greater petrosal nerve groove on the anterior surface of the petrous part of the temporal bone toward the apex. Upon exiting via the foramen for the greater petrosal nerve, it joins the deep petrosal nerve from the sympathetic plexus of the internal carotid artery to form the nerve of the pterygoid canal. The nerve of the pterygoid canal traverses the canal to reach the pterygopalatine fossa, where its fibers synapse in the pterygopalatine ganglion. Postganglionic fibers follow the second division of the trigeminal nerve (maxillary nerve) through its zygomatic branch and zygomaticotemporal branch to the lacrimal gland and nasal glands. Lesions of the facial nerve involving the lower portion of the motor nucleus and above the geniculate ganglion lead to decreased tear secretion on the affected side.

Nerve to the Stapedius

This branch arises posterior to the pyramidal eminence and travels through a small bony canal to the stapedius muscle, controlling its contraction. Reflexive contraction of the stapedius in response to loud sounds displaces the stapes away from the oval window to reduce pressure transmitted to the inner ear. Absence of the stapedius reflex results in hyperacusis and pain sensitivity to loud sounds. Stapedius reflex testing and threshold measurements are clinically utilized to evaluate the type and location of hearing loss.

Chorda Tympani Nerve

This branch emerges between the point where the nerve to the stapedius originates and the stylomastoid foramen. It courses upward and forward through the chorda tympanic canal, entering the posterior-superior part of the tympanic cavity, where it passes between the long process of the incus and the handle of the malleus. The nerve then exits via the anterior wall of the tympanic cavity, traveling through a bony canal and passing through the petrotympanic fissure to reach the infratemporal fossa. In the infratemporal fossa, it joins the lingual nerve. Its taste fibers mediate taste sensation in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, while its parasympathetic fibers synapse in the submandibular ganglion. Postganglionic fibers from that ganglion innervate the submandibular and sublingual glands.

Additionally, the facial nerve gives off small branches within the bony canal that contribute to the tympanic plexus on the medial wall of the tympanic cavity.

Blood Supply of the Facial Nerve

The intracanalicular and labyrinthine segments of the facial nerve receive blood primarily from branches of the labyrinthine artery. The mastoid and tympanic segments are supplied by the stylomastoid artery and the petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery. Venous drainage occurs mainly through the stylomastoid foramen and the hiatus for the facial canal.