Orbit

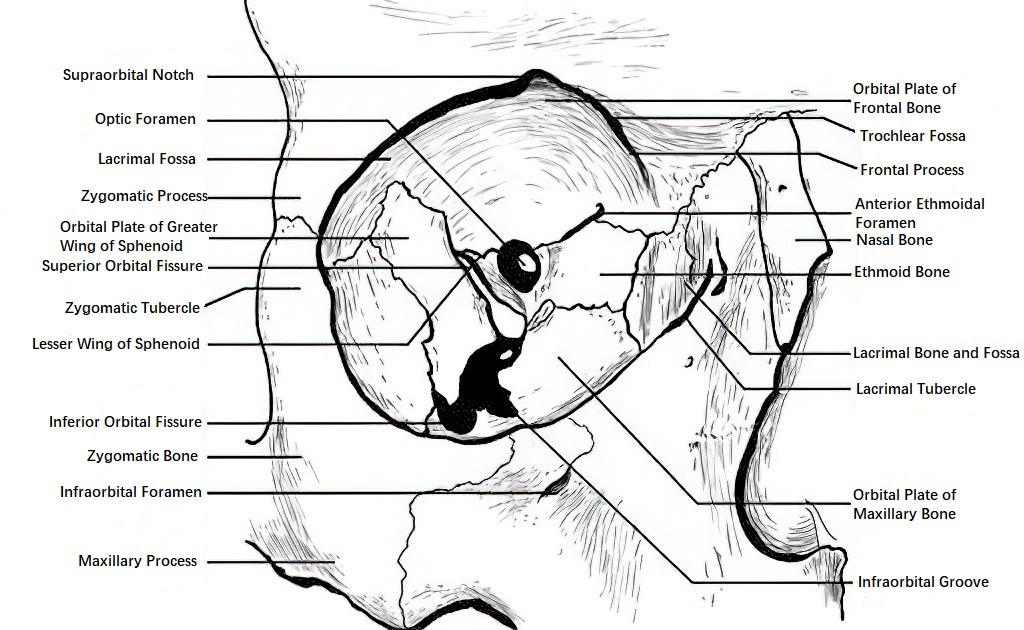

The orbit is a quadrilateral cone-shaped bony cavity. Its opening faces anteriorly, while its apex points posteriorly and slightly medially. It is formed by seven bones: the frontal, sphenoid, ethmoid, palatine, lacrimal, maxillary, and zygomatic bones. In adults, the depth of the orbit measures 40–50 mm, with a volume of 25–28 ml. The orbit has four walls: the superior wall, inferior wall, medial wall, and lateral wall. The lateral wall is relatively thick, with a slightly recessed anterior border, allowing more exposure of the eyeball and a broader lateral visual field, though also increasing the risk of trauma. The other three walls are thinner and more prone to fractures from external forces, given their proximity to the frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses, which can affect the orbit in cases of sinus disease.

Figure 1 Diagram of the orbital bone structure

Optic Foramen and Optic Canal

The optic foramen, located at the orbital apex, is a circular opening with a diameter of 4–6 mm. The optic canal extends posteriorly and medially from the foramen, slightly upward, into the cranial cavity. It is 4–9 mm long and carries the optic nerve, ophthalmic artery, and sympathetic nerve fibers.

Superior Orbital Fissure

The superior orbital fissure lies at the junction between the superior and lateral walls of the orbit, located just inferior and lateral to the optic foramen. It measures about 22 mm in length and connects the orbit to the middle cranial fossa. The third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, the first branch of the fifth cranial nerve, the superior ophthalmic vein, and some sympathetic nerve fibers pass through it. Damage to this region can affect these structures and result in superior orbital fissure syndrome.

Inferior Orbital Fissure

The inferior orbital fissure is situated between the lateral and inferior walls of the orbit. It transmits the second branch of the fifth cranial nerve, the infraorbital nerve, and the infraorbital vein.

Supraorbital Notch (or Foramen) and Infraorbital Foramen

The supraorbital notch is located along the medial one-third of the superior orbital rim, through which the supraorbital nerve (part of the first branch of the fifth cranial nerve) and blood vessels pass. The infraorbital foramen is located approximately 4 mm below the inferior orbital rim along its medial one-third, through which the infraorbital nerve and the second branch of the fifth cranial nerve pass.

Additionally, the lacrimal fossa is located in the superolateral corner of the orbit, the trochlear fossa lies in the superomedial corner, and the lacrimal sac fossa is located anteromedially. The anterior crest of the lacrimal fossa serves as an important anatomical landmark for lacrimal sac surgeries.

The orbit contains fat tissue that fills spaces between structures such as the eyeball, extraocular muscles, lacrimal gland, blood vessels, nerves, and fasciae, serving as a cushion. There are no lymph nodes within the orbit. A flexible connective tissue membrane, the orbital septum, connects the orbital periosteum with the tarsal plate to form a barrier and separates the orbital contents from the eyelids.

Eyelids

The eyelids are located anterior to the orbit and cover the surface of the eyeball. They consist of an upper lid and a lower lid, whose free margins are referred to as the palpebral margins. The gap between the upper and lower lids is called the palpebral fissure, and the points where they meet medially and laterally are known as the medial canthus and lateral canthus, respectively. In normal primary gaze, the palpebral fissure measures about 8 mm in height, with the upper eyelid covering 1–2 mm of the corneal surface. Near the medial canthus is a small, fleshy mound called the lacrimal caruncle, consisting of modified skin tissue.

The palpebral margin features an anterior and a posterior border. The anterior border is rounded and bears 2–3 rows of eyelashes, whose follicles are surrounded by sebaceous glands (Zeis glands) and modified sweat glands (Moll glands), which open into the follicles. The posterior border is sharp and in close contact with the eyeball surface. Between these two borders lies a gray line, marking the transition between skin and conjunctiva. Along the posterior border, aligned openings of the meibomian glands can be observed. At the medial ends of the upper and lower lid margins are small, papilla-like projections, each containing a tiny opening called the lacrimal punctum.

The eyelids consist of five layers from outermost to innermost:

- Skin Layer: One of the thinnest and most delicate areas of skin on the body, prone to forming fine wrinkles.

- Subcutaneous Tissue Layer: Composed of loose connective tissue and minimal fat, this layer is susceptible to edema in cases of kidney disease or localized inflammation.

- Muscle Layer: Includes the orbicularis oculi muscle and the levator palpebrae superioris muscle. The orbicularis oculi is striated and oriented in a circular pattern parallel to the palpebral fissure. It is innervated by the facial nerve and controls eyelid closure. The levator palpebrae superioris, innervated by the oculomotor nerve, raises the upper eyelid and opens the palpebral fissure. This muscle originates from the common tendinous ring around the optic foramen at the orbital apex and fans out along the superior orbital wall to the orbital rim. Its anterior part forms an aponeurosis that penetrates the orbital septum and attaches to the anterior surface of the tarsal plate, partially passing through the orbicularis oculi to attach to the subcutaneous tissue of the upper eyelid, forming the double eyelid fold. Its middle part consists of smooth muscle fibers (Müller's muscle), which are sympathetic-nerve-dependent and attach to the upper edge of the tarsal plate. Excitation of the sympathetic system causes an elevation of the palpebral fissure. The posterior part forms a tendon that attaches to the conjunctival fornix.

- Tarsal Plate Layer: Formed of dense connective tissue, this crescent-shaped structure is anchored to the orbital margins at its medial and lateral ends by canthal ligaments. Embedded within the tarsal plate are vertically arranged meibomian glands, the largest sebaceous glands in the body. These glands secrete lipids, contributing to the tear film and lubricating the ocular surface.

- Conjunctival Layer: The transparent mucous membrane lining the posterior surface of the tarsal plate is known as the palpebral conjunctiva.

The eyelids receive blood supply from both superficial and deep arterial plexuses. These plexuses arise from branches of the facial artery (external carotid artery) and the ophthalmic artery (internal carotid artery). Around 3 mm from the eyelid margin lies the marginal arterial arcade, while a smaller peripheral arterial arcade is located at the upper edge of the tarsal plate. Venous drainage follows superficial (pre-tarsal) and deep (post-tarsal) routes, ultimately emptying into the internal and external jugular veins and the cavernous sinus. The absence of venous valves in the eyelid veins allows for the potential spread of purulent infections to the cavernous sinus, leading to severe complications.

The lymphatic drainage of the eyelids runs parallel to venous routes, with the lateral eyelids draining into the preauricular and parotid lymph nodes, while the medial eyelids drain into the submandibular lymph nodes. Sensory innervation of the eyelids is provided by the first and second divisions of the trigeminal nerve, serving the upper and lower eyelids, respectively.

Conjunctiva

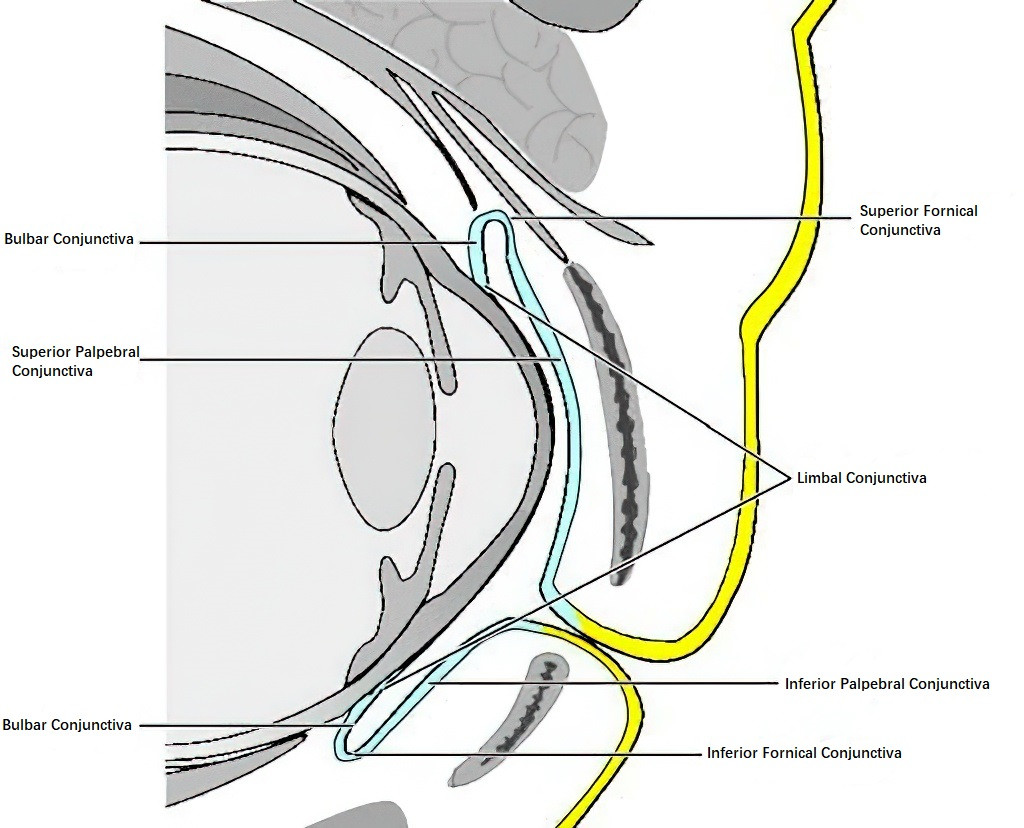

The conjunctiva is a thin, translucent mucous membrane that is soft, smooth, and highly elastic. It covers the posterior surface of the eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva), part of the surface of the eyeball (bulbar conjunctiva), and folds back at the transition between these two areas (fornical conjunctiva). These three regions of the conjunctiva form a sac-like cavity with the palpebral fissure as its opening, referred to as the conjunctival sac. Recent research suggests that the conjunctival stem cells may reside in the fornical conjunctiva and at the lid margin.

Figure 2 Diagram of the conjunctival distribution

Palpebral Conjunctiva

This part is firmly attached to the tarsal plate and cannot be moved. Under normal circumstances, small blood vessels and parts of the meibomian gland ducts can be observed. Approximately 2 mm posterior to the posterior border of the lid margin in the upper eyelid, a shallow groove parallel to the lid margin can be identified, which may easily trap foreign bodies.

Bulbar Conjunctiva

Covering the anterior surface of the sclera, it terminates at the limbus and is the thinnest and most transparent portion of the conjunctiva, allowing for movement. It loosely connects to the sclera through the Tenon’s capsule and fuses with the sclera within 3 mm of the limbus. Lateral to the caruncle, a semilunar fold of the bulbar conjunctiva, called the plica semilunaris, is present and corresponds to the third eyelid in lower animals.

Fornical Conjunctiva

This conjunctiva is loosely organized with multiple folds, facilitating ocular movement. Fibers from the levator palpebrae superioris attach to the superior fornix, while fibers from the sheath of the inferior rectus muscle merge into the inferior fornix.

The conjunctiva consists of an epithelium and a lamina propria. The epithelium comprises 2–5 layers, with thickness and cellular morphology varying depending on the region. The epithelium at the lid margin is stratified squamous, transitioning to cuboidal between the tarsal plate and the fornix and becoming columnar in the fornix. In the bulbar conjunctiva, it returns to a squamous structure, merging with the multilayered squamous epithelium of the limbus before transitioning into the corneal epithelium. Goblet cells, which are unicellular mucous glands, are primarily found within the epithelial layer of the palpebral and fornical conjunctiva. These cells secrete mucus, playing a significant role in the tear film. The lamina propria contains blood vessels and lymphatic vessels and is divided into adenoid and fibrous layers.

The adenoid layer, which is thinner in other regions but more developed in the fornix, contains accessory lacrimal glands (e.g., Krause glands, Wolfring glands) that secrete serous fluids. This layer is composed of a fine reticular connective tissue network, rich in lymphocytes, and may form follicles during inflammation. The fibrous layer consists of interwoven collagen and elastic fibers and is absent in the palpebral conjunctiva.

Conjunctival blood supply originates from the palpebral arterial arcades and anterior ciliary arteries. The palpebral arterial arcade supplies the palpebral conjunctiva, fornical conjunctiva, and the bulbar conjunctiva up to approximately 4 mm peripheral to the limbus. Congestion in these vessels results in conjunctival hyperemia. Meanwhile, the anterior ciliary arteries contribute small episcleral branches around 3–5 mm from the limbus, forming a circumlimbal vascular network that also supplies the bulbar conjunctiva; congestion in this network results in ciliary hyperemia. Differentiating between these two types of hyperemia is critical for determining the location of ocular pathology. The sensory innervation of the conjunctiva is mediated by the fifth cranial nerve.

Lacrimal Apparatus

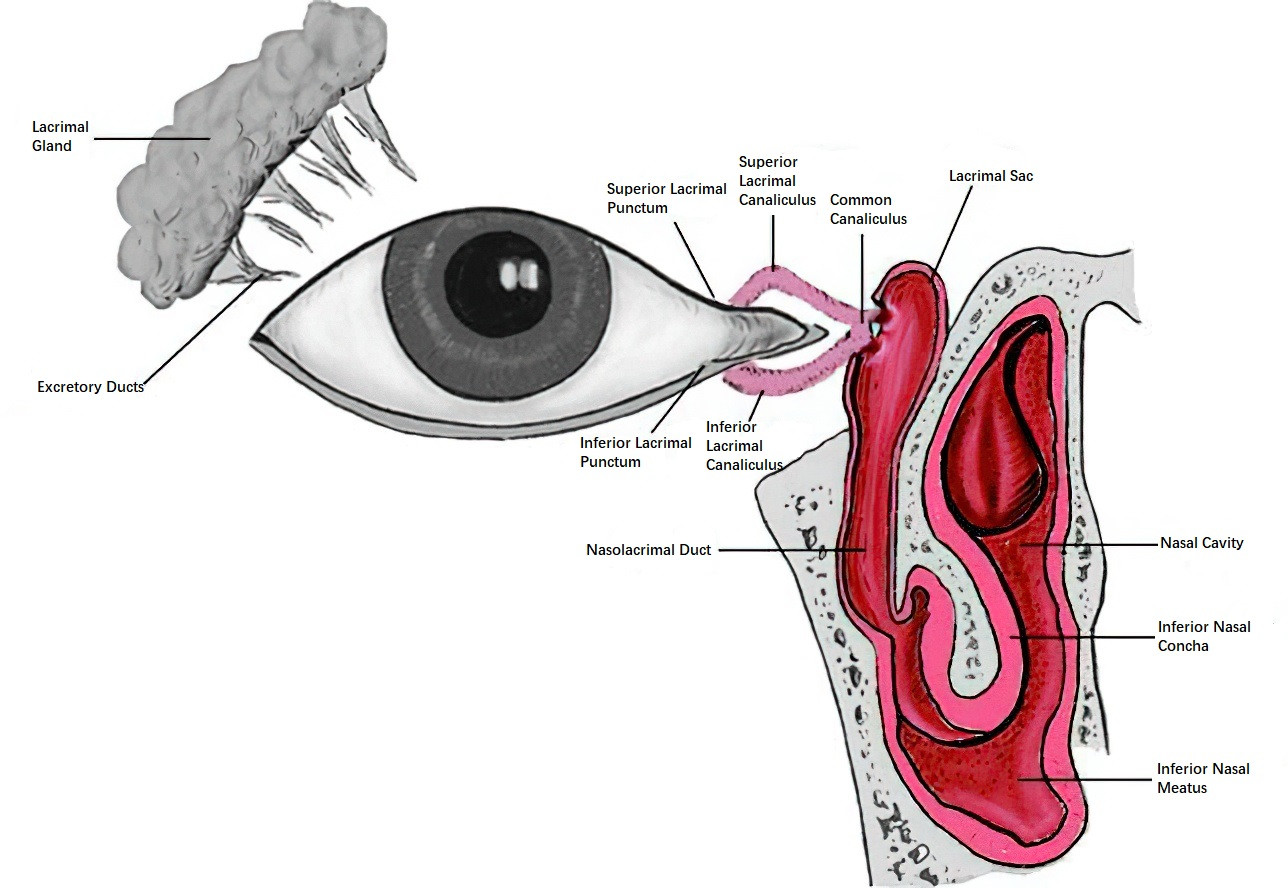

The lacrimal apparatus consists of the lacrimal gland and the lacrimal drainage system.

Figure 3 Diagram of the lacrimal apparatus

Lacrimal Gland

The lacrimal gland is located in the superolateral region of the orbit, within the lacrimal fossa. It is approximately 20 mm in length and 12 mm in width and is anchored to the periosteum of the orbit via connective tissue. The lateral tendon of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle passes through the gland, dividing it into a larger orbital part and a smaller palpebral part. Under normal conditions, the lacrimal gland cannot be palpated externally. The lacrimal ducts, numbering 10–12, open into the superior lateral fornical conjunctiva. As an exocrine gland, the lacrimal gland produces serous fluid and comprises secretory cells and myoepithelial cells. The blood supply is provided by the lacrimal artery, a branch of the ophthalmic artery.

The innervation of the lacrimal gland includes sensory fibers from branches of the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve, parasympathetic fibers from the facial nerve, and sympathetic fibers from the internal carotid plexus, which regulate lacrimal secretion. In addition to the lacrimal gland, accessory lacrimal glands, such as Krause and Wolfring glands located in the fornical conjunctiva, also secrete serous fluids.

Lacrimal Drainage System

The lacrimal drainage system consists of the lacrimal puncta, canaliculi, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct.

Lacrimal Puncta

These are tiny openings marking the starting point for tear drainage. Located on the posterior border of the lid margin, 6.0–6.5 mm from the medial canthus on small papillae, they measure 0.2–0.3 mm in diameter and adhere closely to the conjunctiva covering the eye.

Lacrimal Canaliculi

These are small ducts that connect the puncta to the lacrimal sac. Within 1–2 mm of their origin, the canaliculi run perpendicular to the lid margin, then curve at a right angle to run horizontally for about 8 mm. Near the lacrimal sac, the superior and inferior canaliculi usually merge to form a common lacrimal canaliculus before entering the sac at its superior portion, although in some cases they may enter the sac separately.

Lacrimal Sac

The sac is located posterior to the medial canthal ligament, within the lacrimal fossa of the lacrimal bone. It has a blind superior end, while the inferior end connects to the nasolacrimal duct. The sac measures approximately 10 mm in length and 3 mm in width.

Nasolacrimal Duct

The duct lies within the bony nasolacrimal canal and extends inferiorly and slightly laterally from the lacrimal sac to open into the inferior nasal meatus. It measures approximately 18 mm in length. A semilunar valve-like structure, known as the valve of Hasner, is found at the nasal opening and functions as a barrier.

After tears are produced, they are distributed across the anterior surface of the eye through blinking, pooling at the inner canthus in an area called the lacrimal lake. Tears are then siphoned into the lacrimal sac via the lacrimal puncta and canaliculi, eventually passing through the nasolacrimal duct into the nasal cavity, where they are absorbed by the mucosa. Normal tear production ranges from 0.9 μl to 2.2 μl per minute; when this volume increases by 100-fold or more, excessive tearing (epiphora) occurs—even in the absence of lacrimal duct obstruction. In response to irritation by harmful external substances, reflex tearing is triggered to wash away and dilute the irritants.

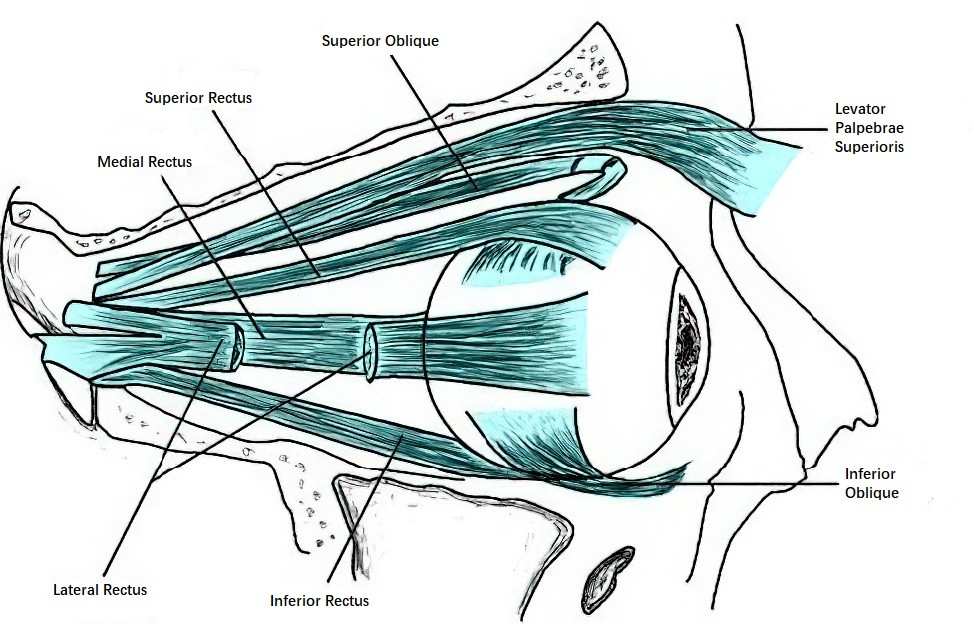

Extraocular Muscles

The extraocular muscles are responsible for the movement of the eyeball. Each eye has six extraocular muscles, which include four rectus muscles and two oblique muscles. The four rectus muscles are the superior rectus, inferior rectus, medial rectus, and lateral rectus. All rectus muscles originate from a common tendinous ring located around the optic foramen at the orbital apex. They extend forward and pass over the equator of the eyeball to attach to the anterior sclera. The attachment points of the rectus muscles differ in their distance from the corneal limbus: the medial rectus is the closest at 5.5 mm, followed by the inferior rectus at 6.5 mm, the lateral rectus at 6.9 mm, and the superior rectus at 7.7 mm, which is the farthest. The primary function of the medial and lateral rectus muscles is to turn the eyeball in the direction of muscle contraction.

Figure 4 Diagram of the extraocular muscles

The superior and inferior rectus muscles are oriented at an angle of 23° relative to the visual axis. In addition to their primary functions of moving the eyeball upward and downward, respectively, they also have secondary functions. The superior rectus contributes to intorsion and adduction as secondary actions, while the inferior rectus contributes to extorsion and adduction.

The two oblique muscles are the superior oblique and inferior oblique. The superior oblique originates from the periosteum of the sphenoid body near the common tendinous ring at the orbital apex. It follows the orbital roof anteriorly to the orbital medial superior margin, where it passes through the trochlea and then redirects posteriorly. It extends beneath the superior rectus to reach the post-equatorial region of the eyeball, attaching to the superior temporal sclera. The inferior oblique originates from the orbital floor at the anterior medial side of the maxillary bone near the lacrimal fossa. It runs between the inferior rectus and the orbital floor, extending upward, outward, and posteriorly, and attaches to the sclera on the temporal inferior post-equatorial region of the eyeball.

The direction of force exerted by the oblique muscles forms an angle of 51° with the visual axis. The primary action of the superior oblique is intorsion, while the inferior oblique primarily performs extorsion. Their secondary actions include depression and abduction for the superior oblique, and elevation and abduction for the inferior oblique.

The extraocular muscles are striated muscles. The lateral rectus is innervated by the sixth cranial nerve, the superior oblique is innervated by the fourth cranial nerve, and the remaining extraocular muscles are innervated by the third cranial nerve.

The blood supply to these muscles is provided by branches of the ophthalmic artery, including the superior and inferior muscular branches, the lacrimal artery, and the infraorbital artery. The lateral rectus receives blood from a branch of the lacrimal artery, while the other rectus muscles are supplied by two anterior ciliary arteries each, which are connected to the major arterial circle of the ciliary body.