The urinary system is composed of a series of tubular structures, including renal tubules, collecting ducts, renal calyces, renal pelvis, ureters, bladder, and urethra. Its primary function is to excrete urine produced by the kidneys. Maintaining the patency of the urinary system is essential for preserving normal kidney function. Any obstruction occurring at any segment of the urinary system can lead to urine accumulation proximal to the obstruction, ultimately resulting in impaired or complete loss of function in the affected kidney. Bilateral obstruction, if present, may lead to kidney failure.

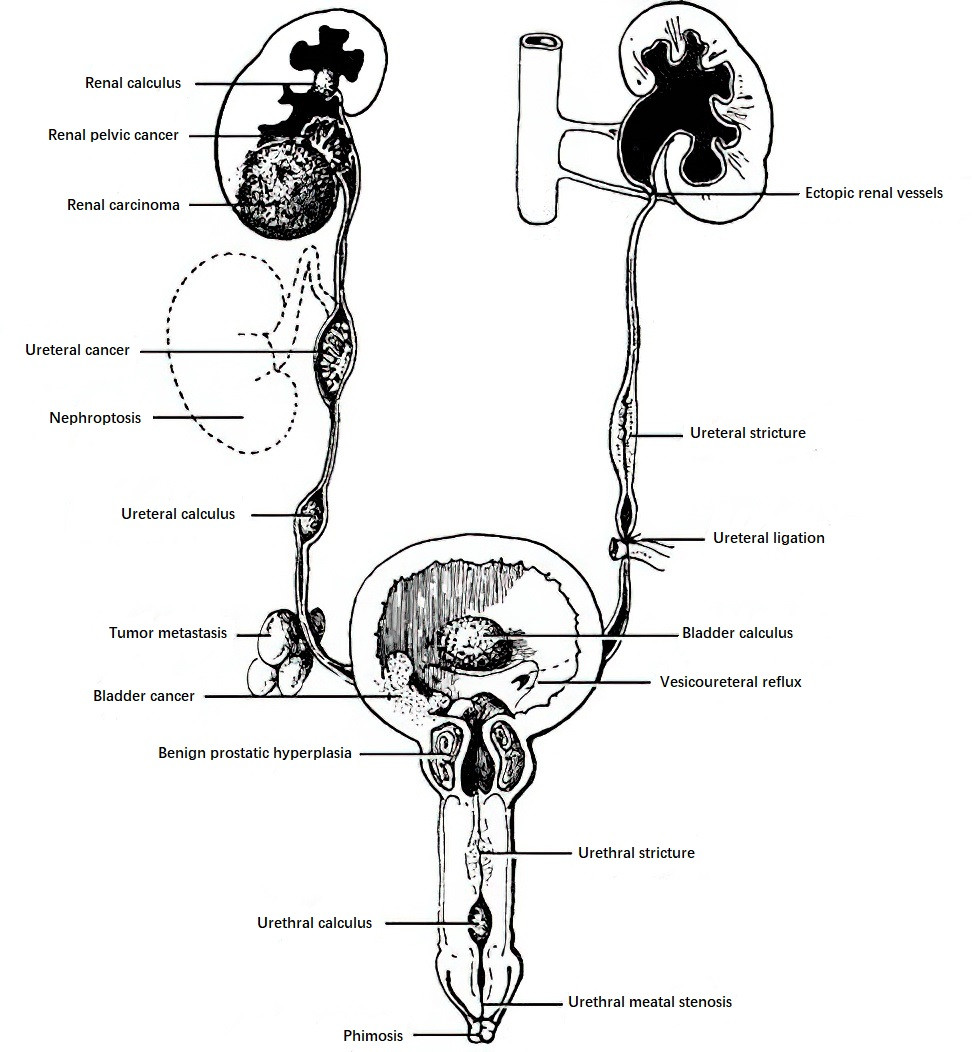

Obstructive lesions are often secondary to or associated with other urological diseases. For instance, urine stasis due to obstruction provides favorable conditions for bacterial growth, leading to infection and stone formation. Moreover, infections and stones further exacerbate the degree of obstruction. Consequently, obstruction, infection, and stones are interrelated, forming a cause-and-effect relationship. Careful attention is required when diagnosing and treating obstructive diseases of the urinary tract. Various diseases can cause urinary tract obstruction, such as congenital anomalies, tumors, and stones.

Figure 1 Common causes of urinary tract obstruction

Etiology and Locations of Obstruction

The causes of obstruction can generally be classified into two main categories: mechanical and dynamic. Additionally, obstruction is further categorized into upper urinary tract and lower urinary tract obstruction based on the affected location.

Mechanical Obstruction

Mechanical obstruction arises from lesions within the urinary system or adjacent organs. It can be further divided into two types based on the underlying cause:

- Congenital Obstruction: This type is caused by congenital malformations of the urinary or reproductive systems, commonly observed in children. Examples include ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) stenosis, retrocaval ureters, ureterocele, ectopic ureteral opening, and posterior urethral valves.

- Acquired Obstruction: This type results from various factors, including tumors, stones, inflammatory strictures, tuberculosis, trauma within the urinary tract, or external compression from fibrosis or tumors in the abdominal or pelvic cavity. Iatrogenic factors, such as damage caused during surgery or endoscopic examination or reactions following tumor radiotherapy, can also lead to obstruction.

Dynamic Obstruction

Dynamic obstruction occurs when there are abnormalities in the musculature or the innervation of urinary tract organs, preventing the smooth flow of urine. This often results in urine stasis. Neurogenic bladder dysfunction is one of the common causes in this category.

Upper Urinary Tract Obstruction

Obstruction located above the bladder, typically involving the renal pelvis, calyces, or ureters, often occurs due to stones, tumors, or lesions compressing the ureters from retroperitoneal conditions.

Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction

Obstruction occurring at the bladder or urethra is commonly caused by conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia or urethral stricture. The causes of obstruction often vary significantly based on the patient’s age and sex.

Pathophysiology

The primary pathological changes involve urine stasis and urinary tract dilation occurring above the site of obstruction. In cases of ureteral obstruction, the ureter initially compensates by increasing the contractile strength of its muscular walls to maintain normal urinary function. However, over time, the muscle gradually loses its ability to compensate, leading to thinning of the ureteral wall, muscular degeneration, and a progressive decline or complete loss of contractility. As the degree of obstruction worsens, pathological changes also extend to the kidney.

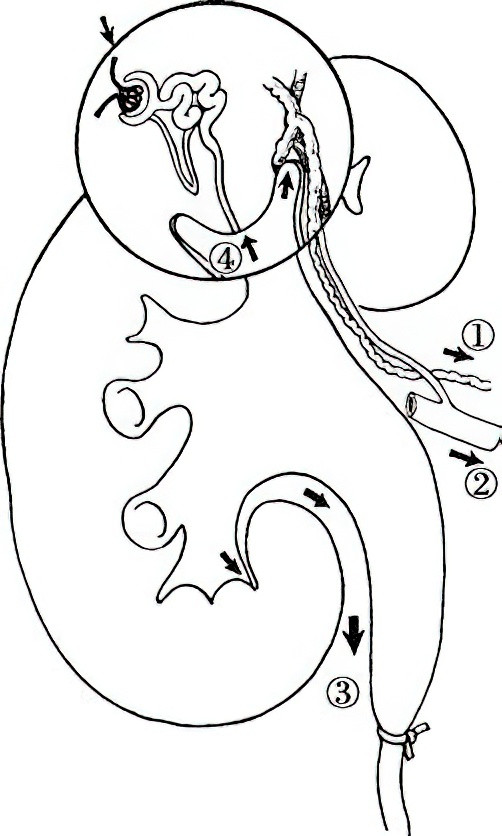

Under normal circumstances, the pressure within the renal pelvis is approximately 10 cmH2O. In the presence of urinary tract obstruction, the pressure in the renal pelvis gradually increases and is transmitted to the renal tubules and glomeruli. When the pressure reaches 25 cmH2O, equivalent to the effective filtration pressure of the glomeruli, glomerular filtration ceases, and urine production is halted. At this stage, urine in the renal pelvis can extravasate into surrounding tissues via the renal tubules, lymphatic vessels, veins, and renal sinus, thereby reducing intrapelvic pressure. As a result, the pressures within the renal tubules and glomeruli also decrease, allowing glomerular filtration to resume. This "safety valve" mechanism within the kidney mitigates acute, short-term damage to renal tissue during obstruction.

Figure 2 Reflux of urine after ureteral obstruction

However, if the obstruction persists over a prolonged period, continuous urine production leads to further increases in intrapelvic pressure. This results in a gradual rise in tubular pressure, compression of adjacent blood vessels, and subsequent renal ischemia, ultimately causing permanent loss of kidney function. Renal parenchymal atrophy that occurs during hydronephrosis is partly due to the direct compressive effects of sustained high intrapelvic pressure and partly attributed to ischemia.

In cases of chronic partial obstruction or intermittent obstruction, the renal pelvis and calyces undergo progressive dilation, the renal papillae atrophy, and the renal parenchyma becomes thinner, eventually turning the kidney into a large, nonfunctional cystic structure. In contrast, during acute complete obstruction, the rapid rise in intrarenal pressure has a greater impact on glomerular and tubular function, significantly impairing processes such as filtration, secretion, and excretion. As a result, renal parenchymal atrophy and renal pelvic dilation are less prominent than in chronic cases.

In lower urinary tract obstruction, the detrusor muscle of the bladder initially compensates by increasing contractility to overcome the obstruction, leading to hyperplasia and thickening of the muscle. The bladder wall may exhibit interlacing bands of hypertrophic muscle bundles, known clinically as "trabeculations." However, prolonged obstruction eventually results in decompensation of the bladder, with reduced contractile strength and the development of residual urine. Overdistension of the bladder can lead to excessive stretching of detrusor muscle fibers and damage to nerve fibers innervating the bladder, further impairing normal bladder contractility.

As compensatory mechanisms fail, the anti-reflux function of the ureterovesical junction is also compromised, resulting in reflux of urine from the bladder into the ureters. This retrograde flow of urine can cause upper urinary tract obstruction and ultimately lead to hydronephrosis.

Urinary stasis following obstruction also predisposes the patient to infection. Bacteria may enter the bloodstream via fissures in the fornices of the renal calyces or through areas where the urothelial lining has thinned, leading to bacteremia. Furthermore, the impaired flow of urine reduces its natural flushing effect, and antimicrobial agents have difficulty penetrating the urinary tract, making infections challenging to control.