Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands are retroperitoneal organs positioned above the kidneys, enclosed together with the kidneys within the perirenal fascia. The left adrenal gland is crescent-shaped, while the right adrenal gland is triangular. The adrenal tissue consists of an outer cortex and a central medulla. The adrenal cortex is further divided into three zones from the outermost to the innermost: the zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis. Each zone has distinct functions: the zona glomerulosa produces mineralocorticoids (e.g., aldosterone), the zona fasciculata secretes glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol), and the zona reticularis synthesizes sex hormones (e.g., androgens). The medulla is composed of chromaffin cells, which secrete catecholamines.

The blood supply to the adrenal glands comes from the superior, middle, and inferior adrenal arteries. The superior adrenal artery originates from the inferior phrenic artery and may at times be absent, the middle adrenal artery arises from the abdominal aorta, and the inferior adrenal artery stems from the renal artery. Adrenal venous drainage typically involves a single vein. The right adrenal vein is shorter and drains into the inferior vena cava, while the left adrenal vein drains into the left renal vein.

Kidneys

The kidneys are the most important excretory organs, facilitating the elimination of metabolic waste via urine production. They play a critical role in regulating water-electrolyte balance and maintaining ionic homeostasis, contributing to the stability of the body’s internal environment. Additionally, the kidneys possess important endocrine functions, secreting erythropoietin, renin, and 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. In adults, the average kidney measures 8–14 cm in length, 5–7 cm in width, and 3–5 cm in thickness, with an average weight of 130–150 g.

The anterior surface of the kidney is convex and faces anterolaterally, while the posterior surface is relatively flat and closely adheres to the posterior abdominal wall. The lateral border is convex, while the medial border features a quadrilateral depression called the renal hilum. The renal hilum serves as the entry and exit site for the kidney’s blood vessels, nerves, lymphatics, and the renal pelvis. These structures are enveloped by connective tissue, referred to as the renal pedicle. The structures within the renal pedicle are generally arranged as follows: from anterior to posterior—renal vein, renal artery, and the terminal end of the renal pelvis; and from superior to inferior—renal artery, renal vein, and the terminal end of the renal pelvis. The renal sinus is the internal extension of the renal hilum into the renal parenchyma and contains the renal vessels, minor and major calyces, renal pelvis, and adipose tissue.

The renal parenchyma is encased by a fibromuscular membrane that adheres closely to the parenchyma and cannot be easily stripped away. This membrane consists of connective tissue and smooth muscle fibers. External to this membrane, there are three layers of coverings from the inside out: the fibrous capsule, the adipose capsule, and the renal fascia. The renal arteries arise from the lateral wall of the abdominal aorta at the level of the L1–L2 intervertebral disc and enter the renal hilum posterior to the renal veins.

Venous drainage within the kidney converges in the renal sinus into 2–3 branches, which unite to form a single trunk that exits the renal hilum and enters the inferior vena cava anterior to the renal artery. The left renal vein is longer and crosses anterior to the abdominal aorta en route to the inferior vena cava, receiving tributaries from the left gonadal vein and left adrenal vein. The right renal vein is shorter and typically does not receive the right gonadal vein.

Ureters

The ureters are retroperitoneal tubular structures originating from the terminal end of the renal pelvis (approximately at the upper border of the second lumbar vertebra) and terminating in the bladder. They are about 20–30 cm in length and are divided into three segments:

- Abdominal segment: From the origin at the renal pelvis to the pelvic inlet.

- Pelvic segment: Extending from the pelvic inlet to the bladder wall.

- Intramural segment: The portion that traverses the bladder wall.

The ureter has three physiological narrowings:

- The proximal narrowing at the junction of the renal pelvis and the ureter.

- The middle narrowing where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels.

- The distal narrowing within the bladder wall, which is the narrowest segment of the ureter. These points of narrowing are common sites for the impaction of ureteral calculi.

Bladder

The bladder is a muscular, sac-like organ responsible for the temporary storage of urine. Its shape, size, position, and wall thickness vary according to the amount of urine contained and the condition of adjacent organs. In healthy adults, the bladder’s average capacity is 350–500 mL, and its maximum capacity can reach 800 mL. In older individuals, bladder capacity may increase due to reduced detrusor muscle tone.

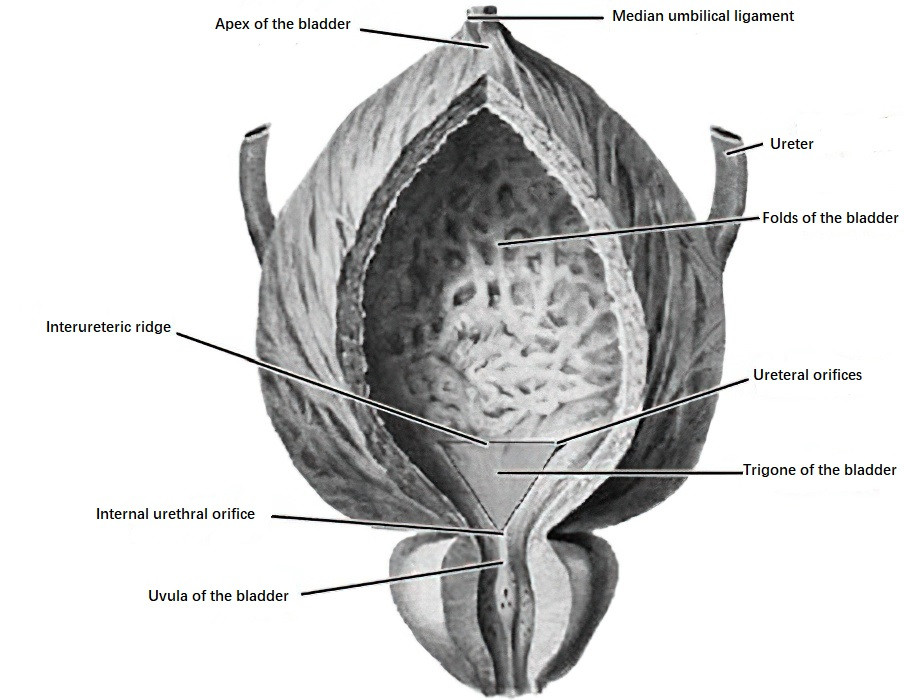

Figure 1 Anatomical structures of the bladder

When empty, the bladder has a tetrahedral shape with four regions: the apex, body, base, and neck, with no distinct boundaries between them. The triangular area defined by the two ureteral orifices and the internal urethral orifice is called the trigone of the bladder. This region is a common site for tumors, tuberculosis, and inflammation and demands attention during cystoscopic examinations. The fold between the two ureteral orifices is called the interureteric ridge, which appears as a pale band under cystoscopy and serves as a marker for locating the ureteral orifices. In males, the posterior aspect of the trigone near the internal urethral orifice forms a ridge-like elevation called the uvula of the bladder, which results from middle lobe prostatic hypertrophy.

Blood supply to the bladder is primarily derived from the superior vesical artery and inferior vesical artery, both branches of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery.

The superior vesical artery originates from the proximal segment of the umbilical artery, supplying the upper and middle bladder.

The inferior vesical artery arises slightly below the umbilical artery and supplies the bladder base, seminal vesicles, and the inferior pelvic segment of the ureter.

Bladder venous drainage does not parallel the arterial supply. Instead, the veins form rich venous plexuses within or on the bladder walls. These plexuses consolidate at the lower lateral bladder into the vesical venous plexus or vesicoprostatic venous plexus (in males), which drains into the internal iliac vein. Neural innervation of the bladder includes sympathetic, parasympathetic, and visceral sensory nerves.

Urethra

The male urethra, in adults, has an average diameter of 5–7 mm and a length of 16–22 cm. It assumes an S-shaped curve under normal conditions, expands during urination and ejaculation, and remains closed in a slit-like state at rest. It is divided into the prostatic, membranous, bulbous, and penile segments. Clinically, the bulbous and penile segments are referred to as the anterior urethra, while the prostatic and membranous segments are considered the posterior urethra. The male urethra contains three narrowings, three dilations, and two curvatures. The narrowings are located at the internal urethral orifice, the membranous urethra, and the external urethral orifice, with the external orifice being the narrowest part, where urethral calculi are prone to become lodged. The dilations are found in the prostatic urethra, the bulb of the urethra, and the navicular fossa. The curvatures include the fixed subpubic curve, located approximately 2 cm below the pubic symphysis and convex downward and posteriorly, and the movable prepubic curve, found between the root and body of the penis and convex upward and anteriorly. The prepubic curve disappears when the penis is erect or elevated.

The female urethra is shorter, wider, and straighter compared to the male urethra, measuring about 5 cm in length and approximately 6 mm in diameter, which can expand up to 1 cm during dilation. It begins at the internal urethral orifice of the bladder, runs closely along the anterior vaginal wall, and opens into the vestibule of the vagina below the pubic symphysis in a nearly horizontal orientation. The portion of the urethra that traverses the urogenital diaphragm is surrounded by the external urethral sphincter, composed of striated muscle, which functions as a voluntary sphincter. The distal end of the urethra is surrounded by urethral glands, the ducts of which open about 1 cm above the external urethral orifice along the midline, where their length may predispose to infections due to poor drainage. Additionally, the paired paraurethral glands are located in the submucosa of the distal urethra, with ducts opening near or at the lateral edges of the external urethral orifice. Infection in these glands may result in cyst formation and lead to urinary obstruction.

Testes and Epididymis

The testes are the organs responsible for sperm production and the secretion of male hormones. They are located within the scrotum, with one on the left and one on the right. Sperm produced in the testes travel through the seminiferous tubules, straight tubules, and efferent tubules into the epididymis for storage. During ejaculation, sperm are released together with seminal fluid. The testes primarily secrete testosterone as the main androgen. The epididymis is situated closely along the upper and posterior margins of the testes and functions as a site for sperm storage. It also secretes fluids that nourish sperm, promote their maturation, and enhance their motility.

The testes are slightly flattened ellipsoid structures, symmetrically sized on both sides. In adults, the average testis is 4–5 cm in length, about 2.5 cm in width, and approximately 3 cm in anteroposterior diameter. Each testis weighs about 10.5–14.0 g and has a volume of approximately 30 mL. The testes are covered by a smooth outer capsule called the testicular tunic, which has three layers:

- Tunica vaginalis: Derived from the processus vaginalis, it consists of a parietal and a visceral layer, with a serous cavity in between containing fluid that facilitates lubrication, enabling testicular movement within the scrotum.

- Tunica albuginea: Beneath the visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis, it is a thick and dense fibrous layer tightly covering the testicular parenchyma.

- Tunica vasculosa: Situated deep to the tunica albuginea, it is the primary source of blood supply to the testicular parenchyma.

The epididymis has a crescent shape, measures about 5 cm in length, and consists of three parts: the head, body, and tail. The head is the enlarged upper portion formed by the convolutions of the efferent tubules, which eventually merge to form the epididymal duct. The body forms the middle segment, and the tail constitutes the lower segment, both of which are composed of the convoluted epididymal duct. The tunics of the epididymis are continuous with the tunics of the testis and similarly include the tunica vaginalis, tunica albuginea, and tunica vasculosa.

The arterial supply to the testes and epididymis is derived from three sources: the testicular artery and its branches, the artery to the ductus deferens, and the cremasteric artery. Venous drainage primarily occurs through the pampiniform venous plexus, veins accompanying the ductus deferens, the external pudendal vein, and the cremasteric vein.

Ductus Deferens and Spermatic Cord

The ductus deferens, a continuation of the epididymal duct, measures approximately 32 cm in length with an internal diameter of about 0.3 cm. It is divided into four segments: the testicular, spermatic, inguinal canal, and pelvic portions.

The spermatic cord is a round, cord-like structure extending from the upper end of the testis to the deep inguinal ring, measuring about 11–15 cm in length and approximately 0.5 cm in diameter. It consists of the spermatic portion of the ductus deferens, the testicular artery, the pampiniform venous plexus, along with nerves, lymphatic vessels, and other structures. These components provide blood supply, lymphatic drainage, and neural innervation to the testes, epididymis, and ductus deferens. The spermatic cord is enclosed by coverings collectively referred to as the spermatic fascia, which consists of the external spermatic fascia, the cremaster muscle, and the internal spermatic fascia.

Prostate

The prostate is composed of glandular tissue, smooth muscle, and connective tissue. The prostatic portion of the urethra passes through its parenchyma. Secretions from the prostate form a major component of seminal fluid and play a role in nourishing and enhancing sperm motility.

The prostate resembles a chestnut in shape and has a firm consistency. It is divided into the central zone, transition zone, and peripheral zone. Benign prostatic hyperplasia commonly occurs in the transition zone, while prostate cancer frequently develops in the peripheral zone.

The arterial supply to the prostate primarily comes from branches of the inferior vesical artery, the internal pudendal artery, the inferior rectal artery, and the obturator artery. Additional branches from the superior vesical artery, dorsal artery of the penis, and deep artery of the penis also provide blood supply. Venous drainage occurs mainly through the prostatic venous plexus. The prostate contains capillary lymphatic vessels and lymphatic ducts within its capsule and parenchyma. Local lymph nodes shared with the prostate, sacrum, and lumbar spine, such as the sacral promontory lymph nodes or sacral lymph nodes, may serve as pathways for the spread of prostate cancer, leading to bone metastases to the sacrum or lumbar vertebrae. Innervation of the prostate is primarily derived from branches of the lower portion of the pelvic plexus, which form the prostatic plexus, with contributions from the bladder plexus as well.

Seminal Vesicles

The seminal vesicles, also known as seminal glands, secrete a yellowish, viscous fluid that forms part of the seminal fluid composition. Each seminal vesicle is an elongated sac-like organ, mainly composed of coiled tubules. The proximal end of the seminal vesicle is free and presents a bulbous region referred to as the base of the seminal vesicle. The middle segment forms the body of the seminal vesicle, while the distal end is narrow and straight, forming the excretory duct. The excretory duct merges with the terminal ampulla of the ductus deferens to form the ejaculatory duct.

Arterial supply to the seminal vesicles is derived primarily from branches of the artery to the ductus deferens, the inferior vesical artery, and the inferior rectal artery. These branches establish arterial anastomoses with one another. Venous drainage forms the seminal vesicle venous plexus, which communicates with the bladder venous plexus and drains into the internal iliac veins via the bladder veins.

Penis and Scrotum

The penis functions as the excretory duct for the male urinary and reproductive systems and also serves as the primary organ for sexual activity. The scrotum is located below the pubic symphysis, posterior and inferior to the root of the penis, and between the upper medial regions of the thighs. It contains the testes, epididymis, and the lower portions of the spermatic cords.