Patients presenting with symptoms related to the colon, rectum, or anal canal undergo a diagnostic process that includes visual inspection, palpation, digital rectal examination (DRE), and endoscopic evaluation. Based on the findings from these examinations, additional imaging may be considered if necessary.

Common Examination Positions

The patient's positioning plays a critical role in the examination of rectal and anal canal diseases. Incorrect positioning can cause pain or lead to missed diagnoses, so appropriate positions should be selected based on the patient's physical condition and the purpose of the examination.

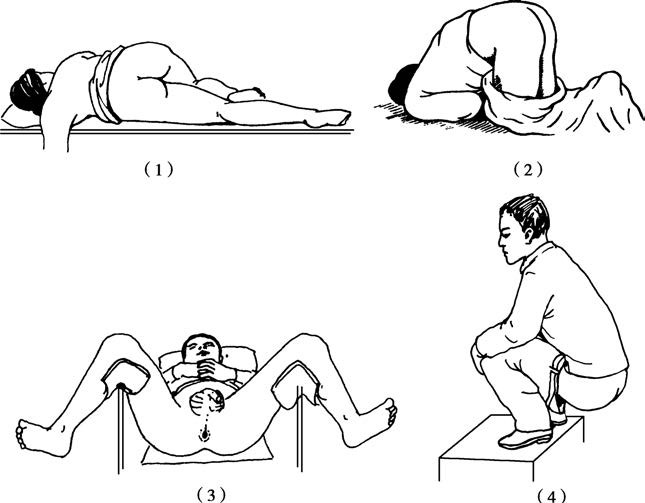

Figure 1 Positions for rectal and anal canal examination

(1) Left lateral position (2) Knee-chest position (3) Lithotomy position (4) Squatting position

Left Lateral Position

This position is commonly used for digital rectal examination.

Knee-Chest Position

This is another standard position for examining the rectum and anus and is also commonly used for prostate massage. However, due to the discomfort and inability of some patients to maintain this position for a prolonged period, its use should be adjusted for elderly or severely ill patients.

Lithotomy Position

This position is often employed in bimanual examinations.

Squatting Position

This is suitable for examinations of rectal prolapse, third-degree internal hemorrhoids, and distal polyps. In the squatting position, the rectum and anal canal are under the greatest pressure. When patients bear down (Valsalva maneuver) or simulate defecation, the rectum may descend by 1–2 cm, allowing internal hemorrhoids, polyps, or prolapsed rectal tissue to be observed extruding from the anus. This is particularly valuable for diagnosing circumferential internal hemorrhoids.

Anal Visual Inspection

Common positions for visual inspection include the left lateral, knee-chest, and lithotomy positions. The intergluteal cleft is spread using the thumbs or three fingers (index, middle, and ring fingers) to observe for redness, swelling, blood, pus, feces, mucus, fistulous openings, external hemorrhoids, wart-like growths, ulcers, masses, or prolapse around the anus. These findings can aid in the analysis and diagnosis of pathological changes:

- Fistulas: Fistulous openings or purulent discharge around the anus may be observed.

- Anal incontinence: A relaxed anal sphincter may be noted.

- Thrombosed external hemorrhoids: A dark purple, round mass may be visible.

- Wart-like growths or ulcers: These may indicate sexually transmitted diseases or specific infections.

- Anal fissures: Linear ulcers located in the posterior midline of the anal canal may be seen.

- Perianal abscesses: Inflammatory masses may be apparent.

Palpation

Palpation initially involves assessing the temperature and elasticity of the skin around the anus. Increased skin temperature and swelling may suggest a perianal abscess, while a cord-like induration may point to an anal fistula.

Digital Rectal Examination

Digital rectal examination is a simple yet critical clinical procedure with significant diagnostic value, particularly for detecting anal canal and rectal cancers. Approximately 70% of rectal cancers can be identified through DRE.

The procedure should follow several steps:

A gloved right hand is lubricated with petroleum jelly, and initial palpation is performed around the anus to evaluate for masses, tenderness, warty lesions, or external hemorrhoids.

The tone of the anal sphincter is tested. Normally, only one finger can be inserted, and the anal ring provides a sensation of constriction. The anorectal ring can be palpated at the posterior aspect.

The rectal and anal walls are examined for pain, fluctuance, masses, or narrowing. If a mass is detected, its size, shape, location, consistency, and mobility are assessed.

The anterior rectal wall, located 4–5 cm from the anal verge, allows for palpation of the prostate in males or the cervix in females. It is essential to distinguish these structures from pathological masses to prevent misdiagnosis.

A bimanual examination may be performed if needed, depending on specific diagnostic requirements.

After withdrawing the finger, the glove is checked for blood or mucus. If blood is detected without a palpable lesion, a colonoscopy should be considered.

Digital rectal examination can reveal the following common conditions:

- Hemorrhoids: Internal hemorrhoids, which are typically soft and difficult to palpate, may feel firm if thrombosis has occurred. Tenderness or bleeding may also be present.

- Anal fistulas: A cord-like structure or a firm nodule at the internal opening of the fistula may be felt by probing from the external opening toward the anus, often during bimanual examination.

- Rectal polyps: Soft, mobile, round masses can be palpated. Multiple polyps may feel like variably sized, soft nodules. Polyps with significant mobility may have a stalk that can be detected.

- Anal canal and rectal cancers: Irregular, hard nodules, ulcers, or cauliflower-like growths within the anal canal or rectum may be palpable. Narrowing of the rectal lumen or mucus, blood, and pus adhering to the glove may be observed.

- Rectal prolapse: Palpation of the rectal cavity determines whether it is empty, aiding in an initial assessment of mucosal prolapse.

Digital rectal examination can also identify extrarectal conditions, such as:

- Prostatitis

- Pelvic abscesses

- Acute adnexitis

- Presacral tumors

Hard nodules detected in the rectovesical or rectouterine pouch may suggest metastatic tumor seeding in the peritoneal cavity.

Endoscopic Examination

Anoscopy

Anoscopy (also known as anal speculum) generally has a length of 7 cm with varying internal diameters and is used for the assessment of low rectal and anal diseases. The knee-chest or lateral recumbent positions are commonly adopted during anoscopy. Prior to performing anoscopy, a visual inspection and digital rectal examination should first be conducted. If the patient presents with local inflammation, anal fissures, menstruation (in women), or experiences significant pain during digital rectal examination, anoscopy should be temporarily postponed. In addition to inspection, simple procedures such as biopsy collection can also be performed during anoscopy.

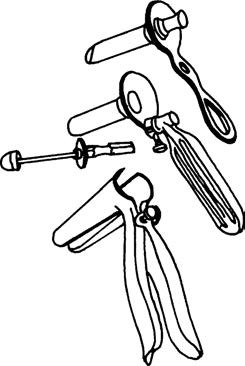

Figure 2 Commonly used anoscopes

Procedure

The anoscope is held in the right hand with the thumb pressing the obturator. The tip of the anoscope is lubricated. The left hand separates the buttocks, and the anoscope is gently pressed against the anus momentarily before being slowly inserted. It should first be directed toward the umbilicus through the anal canal and then angled toward the sacral recess. After the anoscope is fully inserted, the obturator is withdrawn, and attention should be paid to whether the obturator displays any bloodstains. The lighting is adjusted, and the anoscope is withdrawn slowly while observing the mucosal color and noting the presence of ulcers, bleeding, polyps, tumors, or foreign bodies. Particular attention is given at the dentate line to determine the presence of internal hemorrhoids, internal openings of anal fistulas, anal papillae, or inflamed anal crypts.

Recording of Perianal Lesions

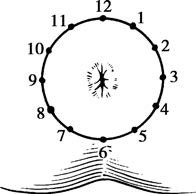

Lesions identified during visual inspection, digital rectal examination, and anoscopy are recorded using a clock-based mapping method, with the patient's position explicitly stated. If the knee-chest position is used, the posterior midpoint of the anus is designated as 12 o’clock and the anterior midpoint as 6 o’clock. In the lithotomy position, the orientation is reversed.

Figure 3 Clock-based mapping method for recording anal examination findings (Lithotomy position)

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy is currently the most direct and accurate method for diagnosing colorectal diseases. It has significantly improved the detection and diagnosis rates of conditions involving the colon, rectum, terminal ileum, and cecum. Additionally, colonoscopy allows for therapeutic interventions such as polypectomy, hemostasis for lower gastrointestinal bleeding, decompression of colonic volvulus, and dilation of benign anastomotic strictures in the colon or rectum. Complete intestinal preparation is typically required before colonoscopy. Advanced techniques, including electronic chromoendoscopy and magnified colonoscopy, are increasingly being adopted in clinical settings.

Imaging Studies

X-ray Examination

Barium enema X-ray was once widely used in the diagnosis of colonic diseases. Dual-contrast (air and barium) imaging has proven effective for detecting small colorectal lesions. However, the use of this method has significantly declined in recent years. Defecography can aid in diagnosing conditions such as constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, rectocele, and rectal prolapse.

CT (Computed Tomography)

CT is an essential tool for diagnosing various colorectal diseases. It plays a key role in staging colon cancer, detecting lymph node metastases, and diagnosing metastatic cancers. In recent years, computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy (CTVC) has been introduced in clinical practice as a diagnostic technique for full visualization of the colon and rectum, generating three-dimensional images similar to those observed during conventional colonoscopy. CTVC offers advantages such as rapid examination and non-invasiveness.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

MRI provides clear visualization of the anal sphincter and pelvic organs, making it especially valuable in diagnosing and classifying anal fistulas, staging rectal cancer (T and N staging), and differentiating postoperative recurrence from other conditions. MRI is considered superior to CT in these applications.

Endorectal Ultrasonography (ERUS)

ERUS clearly displays the layers of the rectal wall and the anal sphincter. It is particularly suitable for preoperative staging of anal canal and rectal tumors, determining the depth of tumor invasion, and identifying lymph node involvement. It is also used in evaluating anal incontinence, complex anal fistulas, perirectal abscesses, and unexplained anal pain.

Colorectal Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

This technique combines endoscopy and ultrasound, providing significant utility in the staging of colorectal cancer, the assessment of intestinal wall tumors, and the evaluation of extraluminal compression effects.

Functional Examination of the Colon, Rectum, and Anal Canal

The functionality of the rectum and anal canal is crucial in bowel movements. Common functional tests include rectoanal manometry, rectal sensory testing, simulated defecation tests (balloon expulsion and balloon retention tests), electromyography of the pelvic floor, defecography, and colonic transit studies.

Stool Testing

Stool tests include fecal occult blood tests, exfoliative cytology, and genetic testing. These methods are useful for the early detection and community-based screening of colorectal tumors.