Anatomy of the Colon, Rectum, and Anal Canal

Colon

The colon consists of the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon, leading into the rectum. The average adult colon is approximately 150 cm in length (120–200 cm). The diameter of the colon varies, gradually decreasing from 7.5 cm at the cecum to 2.5 cm at the terminal sigmoid colon. This narrowing contributes to the higher likelihood of intestinal obstruction in descending and sigmoid colon tumors compared to cecal tumors. The colon is characterized by three anatomical features: haustra, epiploic appendages, and taeniae coli. These features are clinically important for identifying the colon or locating the appendix along the taeniae coli during surgery.

The cecum is connected to the ileum at the ileocecal valve, which serves as a unidirectional sphincter. This valve regulates the flow of contents from the small intestine into the colon, ensuring adequate digestion and absorption in the small intestine while preventing reflux of colonic material back into the ileum. The presence of the ileocecal valve causes colonic obstruction to progress to closed-loop obstruction more easily. However, retaining the ileocecal valve in cases of short bowel syndrome improves prognosis compared to cases where an equivalent length of small intestine is preserved but the ileocecal valve is removed. The cecum measures about 6–8 cm in adults and is an intraperitoneal organ with some degree of mobility.

The hepatic flexure connects the ascending colon to the transverse colon, while the splenic flexure connects the transverse colon to the descending colon. Both flexures are relatively fixed anatomical landmarks of the colon. The ascending and descending colon are retroperitoneal organs, with their anterior and lateral surfaces covered by peritoneum and their posterior surfaces anchored to the posterior abdominal wall by Toldt’s fascia. Toldt’s fascia forms from the fusion of embryonic mesentery with the retroperitoneum. Perforations of the posterior wall of the ascending or descending colon can lead to severe retroperitoneal infections. The peritoneal reflections on the lateral aspect of these regions form a white line, known as the Toldt line, which serves as a surgical landmark for mobilizing the ascending, descending, and sigmoid colon.

The transverse and sigmoid colons are intraperitoneal organs, completely surrounded by peritoneum, and are the most mobile portions of the colon. An excessively long sigmoid mesocolon can predispose to volvulus or defecation difficulties. The wall of the colon consists of the serosa, muscular layer, submucosa, and mucosa.

Rectum

The rectum is located in the posterior pelvis and begins at the third sacral vertebra, where it continues from the sigmoid colon. It descends along the anterior surface of the sacrum and coccyx and transitions into the anal canal at the level of the coccyx, passing through the pelvic diaphragm. The upper rectum has a diameter similar to the sigmoid colon, while the lower rectum expands to form the rectal ampulla, which temporarily stores feces.

The rectum is approximately 12–15 cm long and is divided into two parts—upper and lower—by the reflection of the peritoneum. The upper rectum’s anterior and lateral surfaces are covered by peritoneum, and the anterior peritoneal reflection forms the rectovesical pouch in males or the rectouterine pouch in females. These pouches are clinically significant as they may collect inflammatory fluid or harbor metastasizing tumors, which can be palpated via digital rectal examination. Abscesses in the pelvis can also be drained through the rectum’s anterior wall at this site. The lower rectum lies entirely extraperitoneally.

The lower rectum in males is anteriorly adjacent to the bladder base, pelvic ureters, ampulla of the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and prostate, separated by the rectovesical fascia. In females, the lower rectum is anteriorly adjacent to the posterior vaginal wall, separated by the rectovaginal fascia. Posteriorly, the rectum is related to the sacrum, coccyx, and piriformis muscle.

For clinical purposes, the rectum is further divided into three segments: upper, middle, and lower. These correspond to distances of 10–15 cm, 5–10 cm, and within 5 cm from the dentate line, respectively. Treatment protocols differ between cancers of the upper rectum and those of the middle and lower segments.

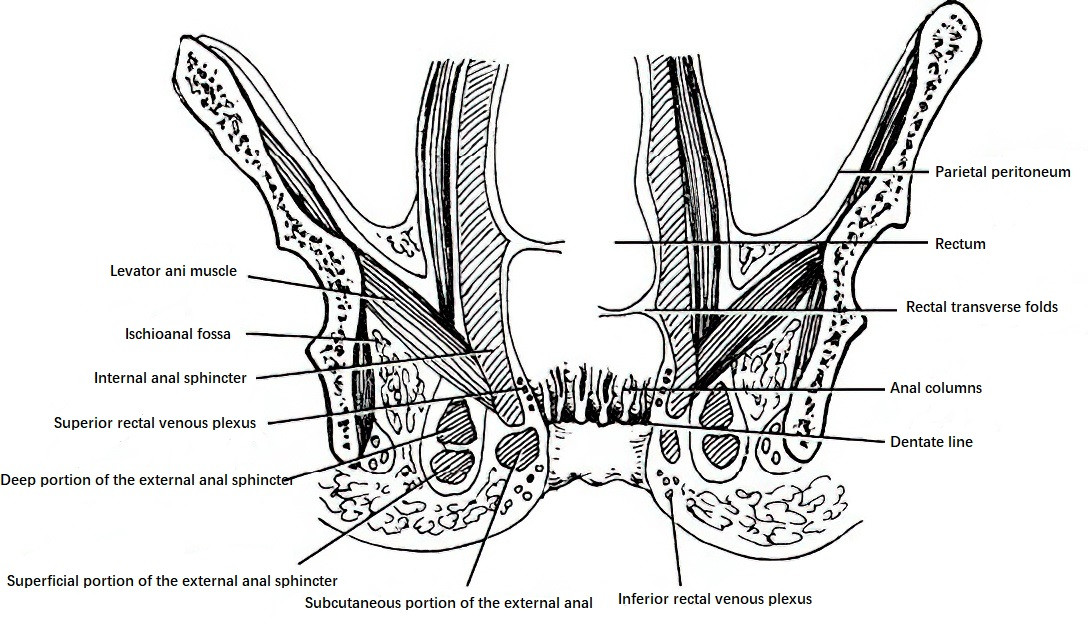

The muscular structure of the rectum is similar to that of the colon. At the lower rectal end, the circular muscle layer thickens to form the internal anal sphincter, which is composed of involuntary smooth muscle under autonomic nervous control. This sphincter maintains resting rectal pressure and keeps the anal canal closed but does not contribute to voluntary anal control. The longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum connects at its lower end with the levator ani muscle and the internal and external anal sphincters.

The rectal mucosa adheres closely to the rectal wall. Within the rectal ampulla, it forms three crescent-shaped transverse folds containing fibers of the circular muscle layer, known as rectal valves. At the distal end, where the rectum narrows to join the closed, constricted anal canal, the mucosa forms 8–10 longitudinal ridges called anal columns. Between the bases of the anal columns are crescent-shaped folds called anal valves, which, along with the base of the anal columns, enclose spaces known as anal sinuses. The openings of the anal glands are located in these sinuses, where debris may accumulate and infections can occur, potentially leading to anal sinusitis, anal fistulas, or ischiorectal abscesses. Small triangular elevations at the junction of the anal valves and columns, called anal papillae, are present. The dentate line, a serrated circular line formed at the junction of the rectum and anal canal, serves as an important anatomical boundary.

Figure 1 Longitudinal cross-section of the rectum and anal canal

Rectal Mesentery

The upper rectum has a well-developed mesentery, while the middle and lower rectum are surrounded on their posterior and lateral sides by a crescent-shaped, 1.5–2.0 cm thick layer of connective tissue. This connective tissue contains arteries, veins, lymphatics, and abundant fat, forming the mesorectum.

Anal Cushions

Anal cushions are located at the junction of the rectum and anal canal, also referred to as the anorectal transition zone (hemorrhoidal zone). This zone forms a 1.5 cm wide, ring-shaped layer of sponge-like tissue rich in blood vessels, connective tissue, and fibro-muscular tissue interwoven with smooth fibers of the Treitz muscle. The Treitz muscle forms a supportive network around the rectal venous plexus, anchoring the anal cushions to the internal anal sphincter. Anal cushions act like a gel pad, assisting the sphincter in sealing the anus. Current understanding suggests that the downward displacement of anal cushions underlies the formation of hemorrhoids.

Anal Canal

The anal canal extends from the dentate line to the anal verge, measuring about 1.5–2 cm in length. The upper portion of the anal canal is covered with transitional epithelium, while the lower portion is lined with keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The canal is surrounded by the internal and external anal sphincters, remaining closed at rest due to their circular contraction. It is classified into the anatomical anal canal and the surgical anal canal. The significant majority of anal diseases occur within 1.5–2 cm above and below the dentate line, encompassing a region approximately 3–4 cm in length, which is referred to as the surgical anal canal.

The dentate line, marking the junction between the rectum and the anal canal, represents the boundary between the endoderm and ectoderm in embryonic development. The blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic drainage above and below this line differ, making it an important anatomical marker with clinical significance.

The intersphincteric groove lies between the dentate line and the anal verge, marking the junction of the lower border of the internal sphincter and the subcutaneous portion of the external sphincter. Although not visually prominent, a shallow groove can be felt during digital rectal examination, known as the white line.

Muscles of the Rectum and Anal Canal

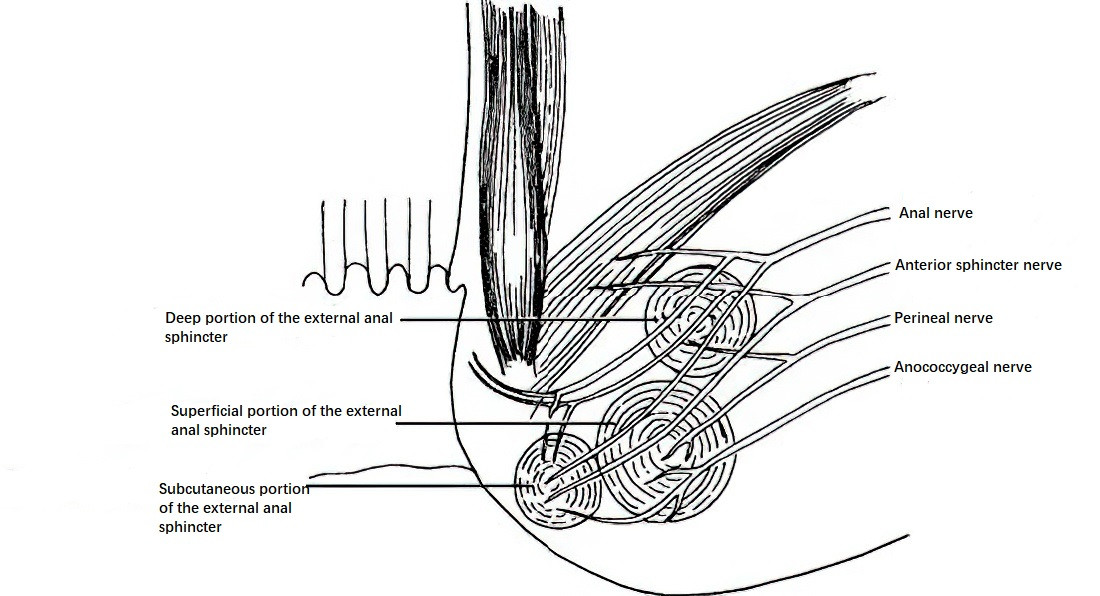

The internal anal sphincter consists of involuntary smooth muscle, while the external anal sphincter is composed of voluntary striated muscle arranged in three segments: subcutaneous, superficial, and deep. The subcutaneous portion lies beneath the skin at the anal verge and is located below the internal anal sphincter. The superficial portion is located deep to the subcutaneous part, while the deep portion lies underneath the superficial segment, separated by fibrous bundles.

The external anal sphincter forms three muscular rings:

- The deep ring is the upper ring, merging with the puborectalis muscle, and is attached to the pubic symphysis. Its contraction lifts the anal canal upward.

- The middle ring is the superficial segment attached to the coccyx, whose contraction pulls the anal canal posteriorly.

- The lower ring is the subcutaneous portion connected to the anterior perianal skin, whose contraction pulls the canal anteriorly and downward.

The simultaneous contraction of all three rings strengthens the function of the anal sphincter, ensuring a tightly closed anal canal.

The levator ani muscle is located around the rectum and, together with the coccygeus muscle, forms the pelvic diaphragm. There is one on each side, and its fibers are arranged into the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles. The levator ani originates from the lateral walls of the pelvis and inserts obliquely into the lower rectal wall on both sides, forming a funnel-shaped musculature. It plays an important role in supporting the pelvic organs, assisting in defecation, and maintaining anal continence.

The anorectal ring is a strong muscular ring encircling the anorectal junction. It is composed of the internal anal sphincter, the lower fibers of the longitudinal layer of the rectal wall, the superficial and deep portions of the external anal sphincter, and the adjacent fibers of the puborectalis muscle. This ring is palpable during digital rectal examination. It is a critical structure for maintaining anal continence, and accidental complete transection of this structure during surgery can lead to fecal incontinence.

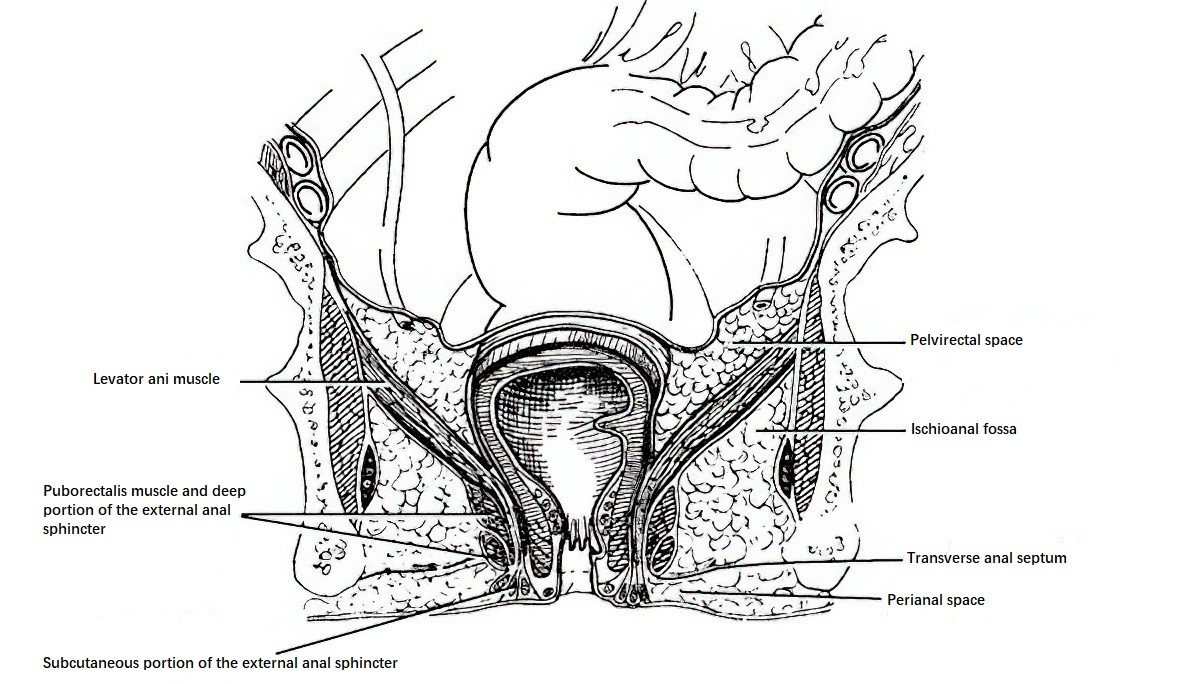

Perirectal and Perianal Spaces

Several spaces are located around the rectum and anal canal, serving as common sites of infection. These spaces are filled with fatty connective tissue, have sparse nerve distribution, and are thus less sensitive to pain. Infections in these regions often go unnoticed until an abscess forms, prompting medical attention.

The spaces above the levator ani muscle include:

- Pelvirectal space: Located on either side of the rectum, situated above the levator ani muscle and below the pelvic peritoneum.

- Retrorectal space: Situated between the rectum and sacrum, communicating with the bilateral pelvirectal spaces.

The spaces below the levator ani muscle include:

- Ischiorectal fossa (also known as ischioanal fossa): Located beneath the levator ani muscle and above the transverse anal septum. The left and right ischiorectal fossae communicate posteriorly behind the anal canal, forming what is also referred to as the deep postanal space.

- Subcutaneous perianal space: Found below the transverse anal septum and between the skin. The left and right subcutaneous perianal spaces also communicate posteriorly behind the anal canal, forming what is called the superficial postanal space.

Infections in these spaces can penetrate the skin or be surgically drained, often resulting in anal fistulas. These abscesses and their clinical implications are significant in medical practice.

Figure 2 Perirectal and perianal spaces

Blood Supply, Lymphatics, and Innervation of the Colon

The blood supply to the colon from the cecum to the distal descending colon arises from the superior mesenteric artery, which gives rise to the ileocolic artery, right colic artery, and middle colic artery. The distal descending colon is supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery, which branches into the left colic artery and several sigmoid arteries. The veins parallel the arteries in nomenclature and drainage pattern, emptying into the superior and inferior mesenteric veins, which then join the portal vein.

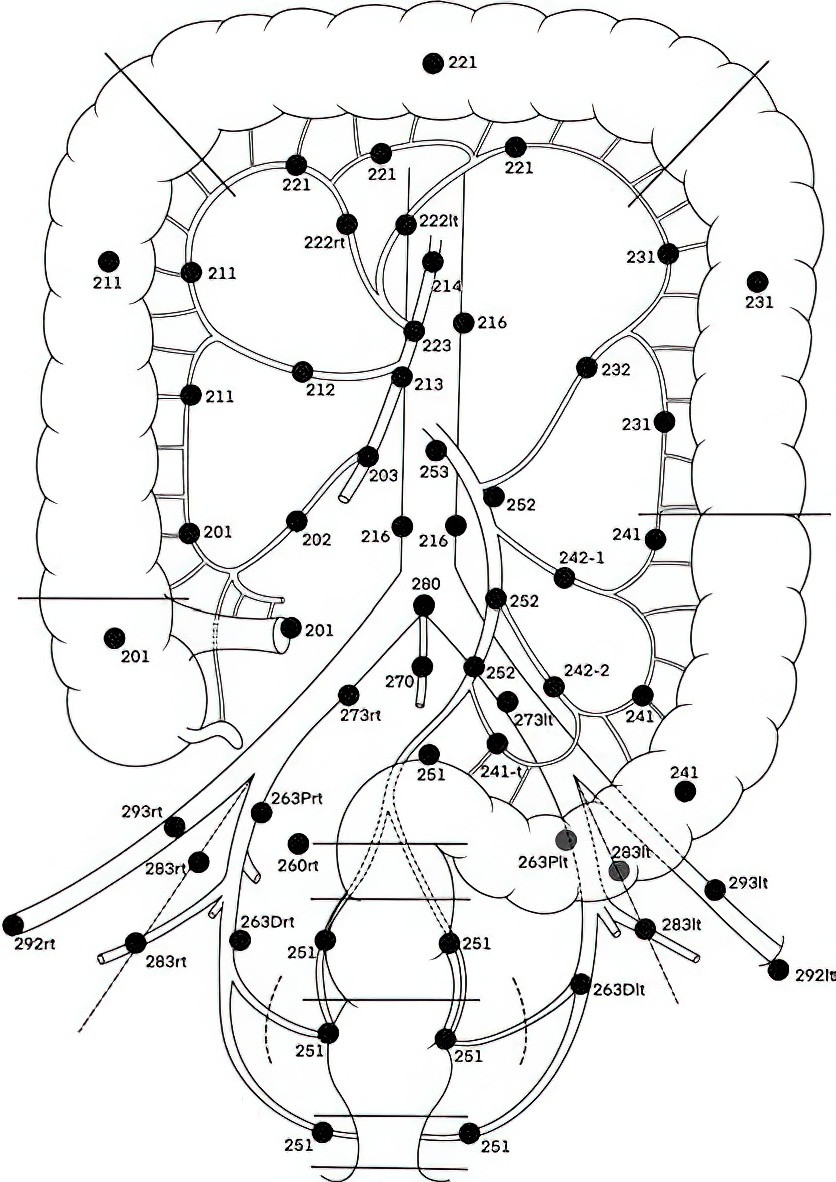

The lymph nodes of the colon are categorized into four groups: epicolic nodes, paracolic nodes, intermediate nodes, and central nodes. The central nodes are located at the origins of the colonic arteries and around the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, with efferent lymphatics draining into the para-aortic lymph nodes.

In the classification and description of colorectal lymph nodes, a three-digit system is commonly used. The hundreds digit represents the anatomical location, with the number 2 for colorectal lymph nodes. The tens digit corresponds to the main artery in the region, where 0 denotes ileocolic, 1 denotes right colic, 2 denotes middle colic, 3 denotes left colic, 4 denotes sigmoid, and 5 denotes the inferior mesenteric and superior rectal arteries. The units digit reflects the lymph node station, based on the direction of lymphatic flow from the paracolic region toward the center. For example, 1 denotes paracolic nodes, 2 denotes intermediate nodes, and 3 denotes central nodes. Using this system, "253" refers to the central lymphatic nodes adjacent to the inferior mesenteric artery.

Figure 3 Lymph node numbering of the colon and rectum

The parasympathetic innervation of the colon is supplied by the vagus nerve and pelvic nerves. The vagus nerve primarily supplies the proximal portion of the colon, while the pelvic nerves innervate the distal colon and rectum. The sympathetic fibers to the colon originate from the superior and inferior mesenteric plexuses.

Blood Supply, Lymphatics, and Nerves of the Rectum and Anal Canal

Arteries

The arterial supply above the dentate line primarily originates from the superior rectal artery (also known as the superior hemorrhoidal artery), which is the terminal branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. Additional supply comes from the middle rectal artery and the median sacral artery, both branches of the internal iliac artery. Below the dentate line, blood supply is provided by the anal canal artery. These arteries form extensive anastomoses with one another.

Veins

Two major venous plexuses are present in the rectum and anal canal. The superior rectal venous plexus is located above the dentate line in the submucosa. It converges into several smaller veins, passes through the rectal muscular layer, and eventually forms the superior rectal vein (also known as the superior hemorrhoidal vein), which drains into the inferior mesenteric vein and then the portal vein. The inferior rectal venous plexus lies below the dentate line and drains into the inferior rectal veins and anal canal veins. These veins ultimately flow into the internal iliac vein and the internal pudendal vein, returning to the inferior vena cava.

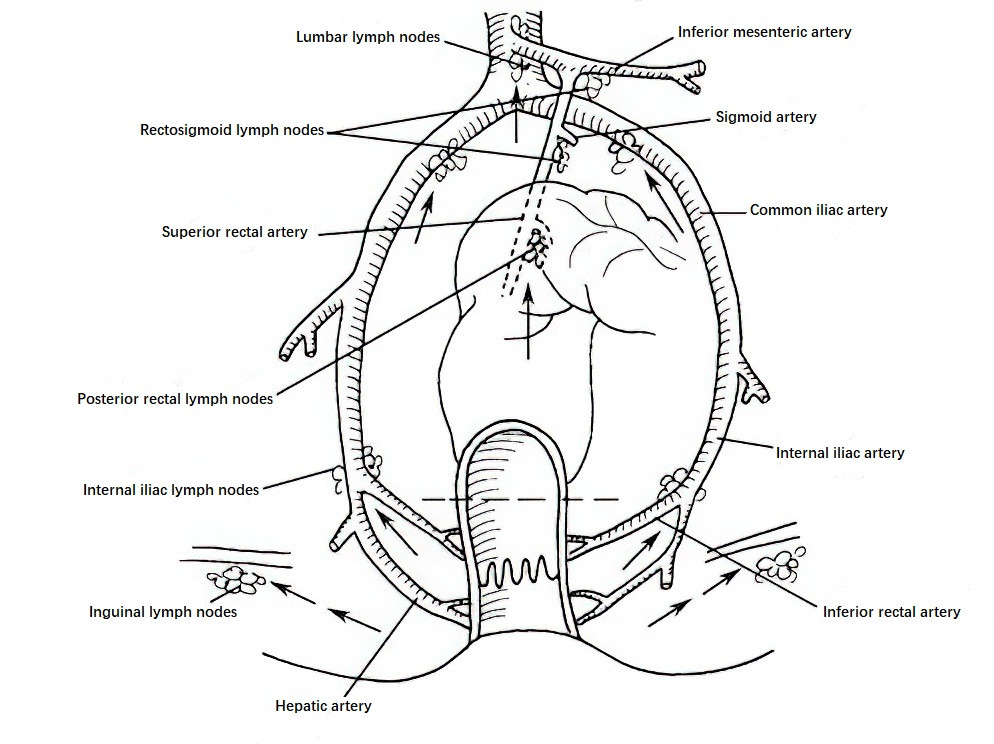

Lymphatics

Lymphatic drainage in the rectum and anal canal is divided into two groups based on the boundary defined by the dentate line. Above the dentate line, lymphatic drainage occurs in three directions. The primary pathway is upward along the superior rectal artery to the lymph nodes around the inferior mesenteric artery. This route represents the main lymphatic drainage of the rectum. Additional pathways include lateral drainage alongside the middle rectal artery to the internal iliac lymph nodes on the lateral pelvic walls and downward drainage through the levator ani muscle to the ischiorectal fossa, following the anal canal artery and internal pudendal artery nodes to the internal iliac nodes.

Figure 4 Lymphatic drainage of the rectum and anal canal

Below the dentate line, lymphatic drainage occurs in two directions. The first pathway extends downward and laterally, near the perineum and medial thigh, toward the inguinal lymph nodes before eventually reaching the external iliac lymph nodes. The second pathway extends peripherally through the ischiorectal fossa alongside the obturator arterial nodes, draining into the internal iliac nodes. Lymphatic networks from both regions have communicating branches, which explains occasional metastases of rectal cancer to the inguinal lymph nodes.

Nerves

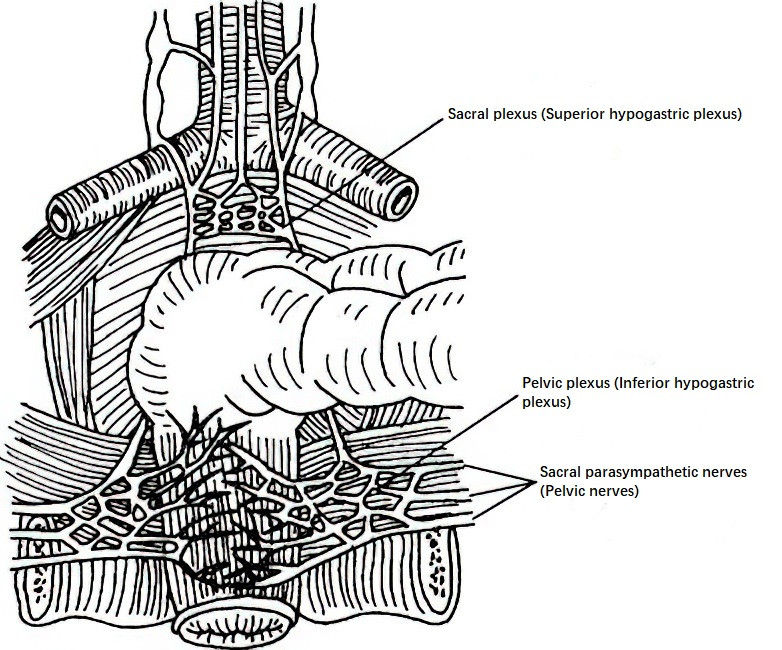

The nerves of the rectum and anal canal are distinctly organized, with the dentate line serving as the boundary. Above the dentate line, the rectum is innervated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, rendering the mucosa above this line insensitive to pain. The sympathetic nerves primarily originate from the pelvic (superior hypogastric) plexus, which is located anterior to the sacrum, beneath the bifurcation of the abdominal aorta. The pelvic plexus divides into left and right presacral nerves, which descend along the lateral rectal ligaments. These nerves consist of postganglionic fibers from the sacral sympathetic trunk and parasympathetic fibers from the second to fourth sacral nerves (S2–S4), forming the inferior hypogastric plexus.

Figure 5 Nerve supply of the rectum

Damage to the presacral nerves may result in a loss of contraction ability in the seminal vesicles and prostate, leading to impaired ejaculation. The parasympathetic innervation of the rectum, arising from the pelvic nerves, plays a key role in regulating rectal function. These nerves include sensory fibers related to the sensation of rectal distension, which become more densely distributed in the lower rectum. Awareness of this distribution is important during rectal surgeries to minimize unintended nerve damage.

The parasympathetic fibers from S2–S4 form the pelvic plexus, which extends to the rectum, bladder, and erectile tissue. These nerves, also known as the cavernous or erection nerves, are crucial for urination and penile erection. Attention is required during pelvic surgeries to avoid injuring these structures.

Below the dentate line, the anal canal and surrounding structures are primarily innervated by branches of the pudendal nerve. Among these, the inferior rectal nerve contains highly sensitive sensory fibers, making the skin of the anal canal a "pain-sensitive area." During perianal infiltration anesthesia, complete infiltration is required, particularly at both sides and the posterior region of the anal canal, to ensure adequate anesthesia.

Figure 6 Nerve supply of the anal canal

Physiological Functions of the Colon, Rectum, and Anal Canal

The primary function of the colon is water absorption, as well as the storage and transport of fecal material. Additionally, the colon absorbs glucose, electrolytes, and certain bile acids. The absorption function predominantly occurs in the right colon. Moreover, the colon secretes alkaline mucus to lubricate the mucosa and produces several gastrointestinal hormones.

The rectum plays a role in defecation, absorption, and secretion. It can absorb small amounts of water, electrolytes, glucose, and some medications. It also secretes mucus to facilitate defecation.

The anal canal’s primary function is the expulsion of feces. The defecation process involves a highly complex neural reflex. The distal rectum plays a central role in the initiation of the defecation reflex and constitutes a critical component of this process. Adequate attention is necessary during rectal surgeries to preserve defecatory function.