Pre-anesthesia assessment is typically conducted during anesthesia outpatient visits or preoperative anesthesia consultations. The primary goals of this assessment are to evaluate and optimize the patient's overall condition, develop an appropriate anesthesia plan, improve their tolerance for surgery and anesthesia, minimize perioperative complications, and ensure perioperative safety. Additionally, pre-anesthesia assessment serves as an important opportunity to alleviate the patient's preoperative anxiety and establish a positive doctor-patient relationship. Anesthesiologists should thoroughly perform pre-anesthesia evaluation and preparation.

Pre-Anesthesia Assessment

Anesthetic drugs and techniques may affect the patient's physiological stability, and surgical trauma alongside intraoperative blood loss places the patient in a state of stress. Furthermore, surgical diseases and comorbid internal conditions introduce additional challenges for anesthesia management. To enhance the safety of surgical anesthesia, a systematic evaluation of the patient’s overall condition and surgical risks is essential prior to the procedure, along with addressing reversible risk factors. For complex or critically ill patients and those undergoing day surgery, evaluation and optimization are generally completed during anesthesia outpatient visits.

Medical History Collection

A comprehensive understanding of the patient’s current medical history, past medical history, personal history, surgical and anesthesia history, medication history, allergy history, and family history is required prior to surgery. A review of the history of all organ systems is performed to assess factors that might increase anesthesia risk, enabling measures to prevent related complications. For example, patients with glaucoma should avoid atropine. For those with a history of anesthesia, detailed inquiries about previous anesthetic methods, medications used, and any complications are necessary.

Physical Examination

Preoperative physical examination should focus on vital signs, general health status, airway conditions, cardiopulmonary function, as well as the spine and nervous system. The clinical status of the patient and the type of surgery guide the emphasis of the examination.

Comprehensive airway evaluation is fundamental for safe airway management. It includes assessments of ventilation conditions, intubation conditions, and surgical airway accessibility in the front of the neck. Risk factors for difficult mask ventilation include challenges in mask seal, obesity, a history of snoring, edentulism, and advanced age. Indicators for estimating intubation difficulty include mouth opening, Mallampati classification, thyromental distance (TMD), neck mobility, horizontal mandibular length, and upper lip bite test. Upper airway obstruction and craniofacial abnormalities are also significant factors contributing to difficult intubation.

In addition to general examination and airway evaluation, targeted assessments are warranted for patients with comorbid medical conditions. For instance, patients with liver disease should be assessed for ascites, spider angiomas, bleeding tendencies, and abnormal mental status. Patients with cerebrovascular disease may display focal neurological deficits. Thorough physical examination facilitates comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s overall health.

Laboratory Tests

Currently, there is no standardized requirement for preoperative laboratory testing. While many earlier studies supported routine preoperative hematologic tests, recent perspectives emphasize that medical history and physical examination are more critical. Routine laboratory tests in asymptomatic patients may hold limited clinical significance. In practice, many hospital protocols recommend elective surgery patients undergo basic tests such as complete blood counts, urinalysis, liver and kidney function tests, coagulation profiles, infection markers, electrocardiograms, and chest X-rays.

For older patients, those with systemic illnesses, or those undergoing complex surgical procedures, additional specialized testing may be recommended based on their specific conditions. For instance, patients with coronary artery disease may require echocardiography and/or coronary artery assessment, while those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) might require arterial blood gas analysis and/or pulmonary function tests. Such evaluations help fully assess surgical and anesthetic risks, guide intraoperative management, and prevent complications.

ASA Classification of Physical Status

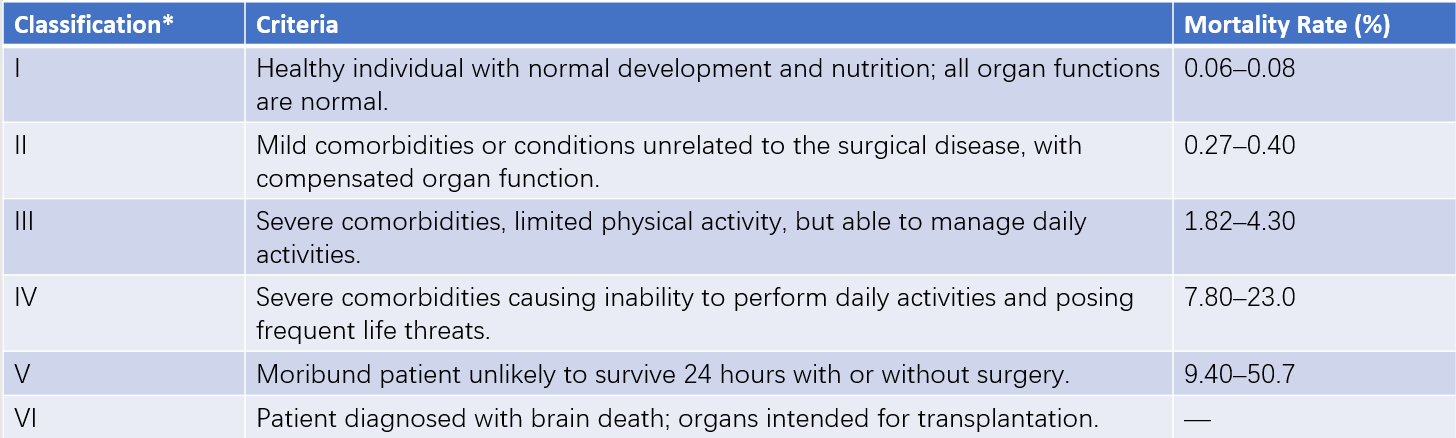

By synthesizing information obtained during the pre-anesthesia assessment, a comprehensive evaluation can be made of the patient’s overall physical condition and tolerance for surgical anesthesia. One commonly used tool is the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System.

Table 1 ASA physical status classification and perioperative mortality rates

*Note: Emergency cases are designated with "Emergency" or "E" following the corresponding ASA classification, indicating a higher risk compared to elective surgeries.

Patients in ASA classifications I–II are generally considered to have good tolerance for anesthesia and surgery with lower risks.

Class III patients, whose organ functions are within compensatory limits, have reduced tolerance to anesthesia and surgery and face greater risks.

Class IV patients, with uncompensated organ dysfunction, face significant risks for anesthesia and surgery, with perioperative mortality rates remaining high even with thorough preoperative preparation.

Class V patients are deemed moribund, facing extreme danger during anesthesia and surgery, rendering them unsuitable candidates for elective surgeries.

There is a strong correlation between perioperative mortality and ASA classification. Studies show that most cases of perioperative cardiac arrest occur in ASA III–IV patients, whose resuscitation success and survival rates are notably lower than those of ASA I–II patients. Thus, the more severe the patient’s condition, the higher the likelihood of perioperative cardiac arrest and mortality.

Anesthesia Evaluation for Comorbid Conditions

For patients with medical comorbidities, a comprehensive evaluation based on the severity of their conditions and the surgical risks is necessary prior to elective surgery. Correcting or improving these comorbidities is essential to ensure that patients are in an optimal state to undergo surgery and anesthesia.

Pre-Anesthesia Preparation

Correction or Improvement of Pathophysiological Conditions

Malnutrition can lead to reduced plasma albumin, anemia, hypovolemia, and certain vitamin deficiencies, which lower the patient’s ability to tolerate anesthesia, surgical trauma, and blood loss. Nutritional status should be improved prior to surgery, with general requirements including hemoglobin ≥ 80 g/L and plasma albumin ≥ 30 g/L. Dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and acid-base disturbances should also be corrected. Middle-aged and elderly patients often have preexisting medical conditions, particularly coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, which require comprehensive evaluation and optimization of organ function before surgery.

For patients with cardiac disease, improving cardiac function is considered critical. Those on long-term beta-blocker therapy for angina, arrhythmias, or hypertension should continue their medication until the day of surgery, as abrupt discontinuation can lead to upregulation of beta receptors, possibly triggering hypertension, tachycardia, or myocardial ischemia. For hypertensive patients, systemic treatment should aim to stabilize blood pressure in preparation for elective surgery, with resting blood pressure ideally below 140/90 mmHg. However, for emergency surgeries or patients with uncontrolled blood pressure due to the primary disease, elevated blood pressure should not be viewed as a contraindication to anesthesia and surgery. The use of centrally acting antihypertensive agents or monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors before surgery is not advisable to prevent refractory hypotension and bradycardia during anesthesia. Other antihypertensive medications can typically be continued until the day of surgery to avoid severe blood pressure fluctuations caused by abrupt withdrawal.

For patients with respiratory diseases, assessments such as lung function tests, arterial blood gas analysis, or imaging studies should be selected based on the severity of the condition. Smokers should ideally stop smoking at least two weeks prior to surgery to improve respiratory function, along with practicing breathing exercises, nebulization therapy, and chest physiotherapy to promote sputum clearance. Acute or chronic pulmonary infections should be controlled with effective antibiotics or other appropriate treatments prior to surgery.

Psychological Preparation

Surgery is inherently a physically invasive treatment, and anesthesia presents an unfamiliar experience for most patients. As a result, preoperative anxiety, tension, or even fear are common emotional responses. These psychological states can lead to excessive excitement of the central and sympathetic nervous systems and impact the perioperative period. Addressing patient concerns during anesthesia outpatient visits or preoperative consultations through empathy and encouragement is beneficial in reducing anxiety and psychological burden. Listening patiently and addressing any questions helps build understanding, trust, and cooperation.

For patients with excessive tension or difficulty sleeping, particularly those with severe cardiovascular conditions, preoperative sedative medications may be appropriate. Those diagnosed with psychological disorders may benefit from support provided by mental health specialists.

Gastrointestinal Preparation

For elective surgeries, the stomach should be emptied to avoid perioperative complications such as aspiration of gastric contents, which can lead to airway obstruction or aspiration pneumonia. Normal gastric emptying typically takes 4–6 hours, but factors such as fear, anxiety, and severe trauma can significantly delay the process.

Elective surgery patients, regardless of the type of anesthesia, are typically advised to fast for at least 6 hours after consuming easily digestible solid foods or non-breast milk dairy products. Fried foods, fatty meals, or meat should be avoided for at least 8 hours before surgery. Patients with delayed gastric emptying or those at high risk for gastroesophageal reflux may require extended fasting periods or medications such as prokinetics and acid suppressants.

For neonates and infants, abstinence from breast milk for at least 4 hours and from easily digestible solid foods, non-breast milk, or infant formula for at least 6 hours is recommended. For patients with normal gastrointestinal motility, clear liquids such as water, fruit juice (without pulp), soda, clear tea, or black coffee (excluding alcoholic beverages) may be consumed in small amounts up to 2 hours before surgery. Emergency cases require careful consideration of gastric emptying status. Patients with a full stomach who require immediate surgery face significant risks of vomiting and aspiration, regardless of whether general, regional, or spinal anesthesia is used.

Preparation of Anesthetic Supplies, Equipment, and Medications

To ensure the safe and smooth conduct of anesthesia and surgery while preventing unexpected events, anesthetic machines, monitoring equipment, supplies, and medications must be prepared and checked beforehand. Anesthetic machines, emergency equipment, and medications should be available for all types of anesthesia.

During anesthesia, monitoring of basic vital signs such as blood pressure, oxygen saturation (SpO2), and electrocardiography (ECG) is considered essential. Depending on the patient's condition, additional monitoring—such as end-tidal carbon dioxide (PETCO2), invasive arterial blood pressure, central venous pressure (CVP), body temperature, or depth of anesthesia—may be utilized. For critically ill patients or those undergoing major surgery, advanced hemodynamic monitoring, such as transesophageal echocardiography or pulse contour cardiac output (PiCCO), may be indicated.

Prior to the induction of anesthesia, a final review of prepared equipment, instruments, and medications is conducted. The anesthesiologist, surgeon, and operating room nurse collaboratively verify key details such as the patient's name, age, planned procedure, fasting status, and allergy history for added assurance.

Informed Consent

Before surgery, the selected anesthesia plan and alternative options, potential perioperative complications, unexpected events, as well as anesthesia-related precautions before and after the operation, are explained to the patient and/or their family. Signing an informed consent form constitutes an integral part of this process.