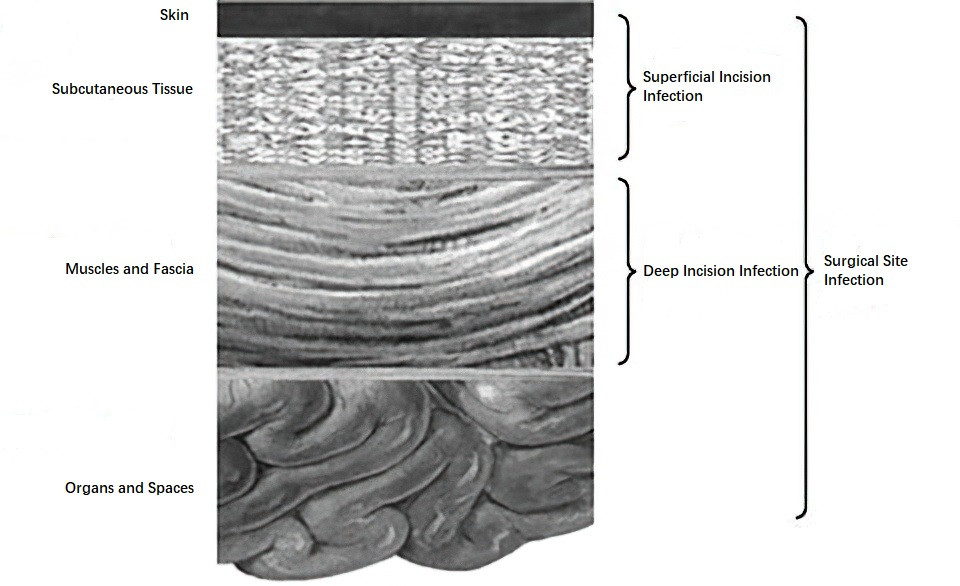

Incision infection refers to an infection that occurs in the tissue of a surgical incision postoperatively. Based on the depth of involvement, it can be divided into superficial incision infection and deep incision infection. Superficial incision infection involves the skin or subcutaneous tissue and typically occurs within 30 days post-surgery. Deep incision infection involves the muscles and deep fascia and occurs within 30 days post-surgery for patients without implants, or within one year for those with implants. Incision infection falls under the broader category of surgical site infections (SSI). It usually develops 3 to 7 days after wound closure, with an incidence ranging from 1% to 20%, making it one of the most common healthcare-associated infections.

Figure 1 Illustrations of superficial incision infections, deep incision infections, and organ/space infections

Etiology and Pathology

The primary causes of incision infection include tissue damage from surgery, suture technique deficiencies, and bacterial contamination. Meticulous surgical technique, minimizing surgical trauma—such as avoiding large-area electrocautery for hemostasis and ensuring no dead spaces remain in the sutured incision—can help reduce the risk of infection. Pathogens responsible for incision infections are primarily derived from the patient's skin flora and intraoperative contamination, with common culprits including Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, streptococci, and Escherichia coli. The type of pathogen is often associated with the nature and location of the incision. Clean incisions are usually infected by Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Contaminated incisions are commonly associated with gram-negative bacilli and anaerobes, while grossly contaminated wounds often involve polymicrobial infections. Patient-related systemic factors—such as age, comorbidities, nutritional status, and immune function—also play a role, as do measures related to the operating room's asepsis, surgical site preparation, and intra- and postoperative incision management.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Incision infections may present with subtle early signs before progressing to typical symptoms.

Local Manifestations

The affected incision site exhibits redness, swelling, pain, and increased skin temperature. On examination, tenderness, induration, or a hollow sensation beneath the incision line may be detected. In cases of abscess formation, fluctuance may be observed. Greyish or foul-smelling exudate is often seen at the incision site.

Systemic Reactions

Systemic signs such as fever, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and elevated serum procalcitonin suggest severe infection, with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) potentially occurring. These cases require immediate incision opening for drainage and treatment with appropriate antibiotics.

Examination of Incision Infection

Suspected incision infections can be evaluated by partial suture removal, aspiration, or incision exploration. The presence of inflammatory fluid, pus, or necrotic infected tissue confirms the diagnosis. For atypical clinical presentations or infections with unclear extents, imaging modalities such as ultrasonography, CT, or MRI can assist in diagnosis.

Laboratory Tests

Direct smears of incision secretions may reveal numerous pus cells, and bacterial cultures of secretions or infected tissue can identify the causative pathogens.

Treatment

In early-stage superficial infection presenting with localized redness or suspected inflammation, application of wet compresses with ethacridine lactate solution and physical therapy can be implemented.

For confirmed infections or abscess formation, partial or complete suture removal is necessary, along with the removal of necrotic tissue and drainage of purulent material.

Cases with significant incision exudate require measures such as gauze packing, placement of rubber drains or negative-pressure drainage.

If infected implants—such as artificial mesh or prostheses—are present in the incision, their prompt removal is mandatory.

Routine antibiotic therapy is generally unnecessary post-drainage of the infected site. However, patients exhibiting systemic inflammatory signs or organ/space infections should receive antimicrobial therapy based on culture sensitivity results.

Prevention

Comprehensive perioperative measures are essential for preventing incision infections. Optimization of the patient’s condition post-admission, such as glycemic control, correction of malnutrition, and improvement of cardiopulmonary function, contributes to reducing infection risk. For colon and rectal surgeries, preoperative bowel preparation with oral antibiotics and mechanical cleansing is beneficial. Non-clean surgeries or clean surgeries with high-risk factors should involve prophylactic intravenous antibiotics administered 30–120 minutes before incision. In prolonged surgeries lasting over 3 hours, exceeding the antibiotic half-life, or accompanied by blood loss over 1,500 mL, intraoperative antibiotic supplementation should be considered.

Precise surgical techniques, including minimizing tissue trauma and avoiding incision contamination, contribute to prevention. Irrigation of the surgical site with normal saline prior to closure enhances cleanliness. Suturing should ensure proper alignment of tissue planes without dead spaces, and antimicrobial-coated sutures may be utilized when available. For heavily contaminated or high-drainage incisions, rubber drains or negative-pressure drainage systems are effective.