Hemorrhagic shock is a common type of surgical shock. It often results from large blood vessel rupture, liver or spleen rupture caused by abdominal trauma, and bleeding due to esophageal or gastric variceal rupture associated with portal hypertension. Shock typically occurs when blood loss exceeds 20% of total blood volume within a short period. Compensation mechanisms for shock vary significantly among patients of different age groups. Young individuals tend to have strong cardiovascular compensatory abilities; even with significant blood loss, some may maintain nearly normal blood pressure for a certain period. Older adults, often with preexisting cardiovascular conditions, are more likely to experience heart failure during massive hemorrhage, leading to a combined presentation of hemorrhagic shock and cardiogenic shock.

Treatment

The primary approach involves replenishing blood volume and actively treating the underlying condition with bleeding control. Both aspects must be addressed simultaneously to prevent further progression of organ damage.

Blood Volume Replacement

Estimated blood loss can be assessed through changes in blood pressure and pulse rate, as shown in Table 5-1. Rapid establishment of intravenous fluid replacement is crucial in hemorrhagic shock, and, if needed, multiple access points for fluid resuscitation can be initiated simultaneously. In some cases, pressurized fluid infusion may be required. Fluid selection is guided by a principle of initially administering balanced saline solutions and artificial colloids via rapid intravenous infusion. Rapid infusion of colloids is particularly effective in restoring intravascular volume and maintaining hemodynamic stability. It also sustains colloid osmotic pressure for a longer duration.

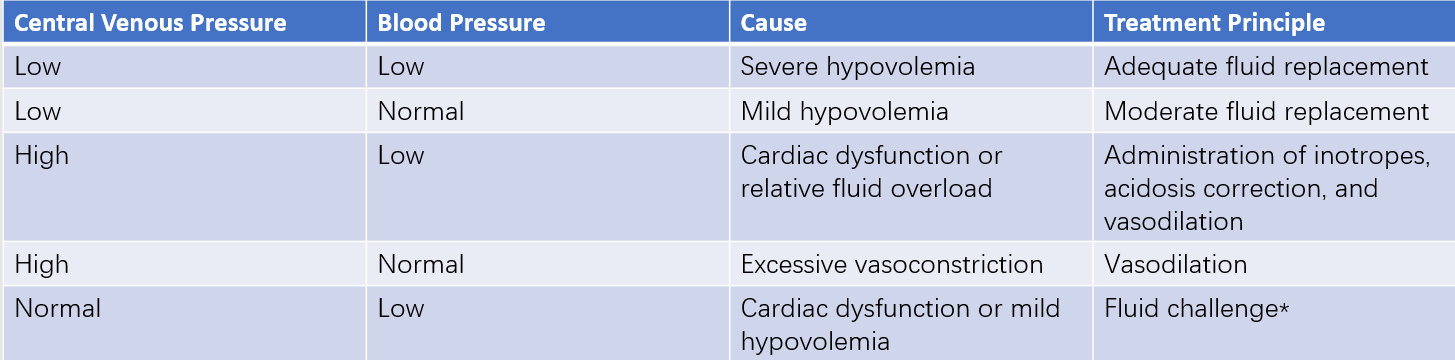

Table 1 Relationship between central venous pressure (CVP) and fluid therapy

Note:

A fluid challenge involves the intravenous infusion of 250 mL of isotonic saline over 5–10 minutes. If blood pressure increases while CVP remains unchanged, hypovolemia is suggested. If blood pressure remains unchanged but CVP rises by 0.29–0.49 kPa (3–5 cmH2O), cardiac dysfunction is indicated.

In general, blood transfusion may not be necessary if the hemoglobin concentration is above 100 g/L. Concentrated red blood cells are typically indicated when the hemoglobin concentration falls below 70 g/L. For levels between 70 and 100 g/L, the decision to transfuse red blood cells is based on factors such as whether bleeding has stopped, the patient’s overall condition, compensatory capacity, and the function of other vital organs. The volume of fluid replacement should be evaluated based on the underlying cause, urine output, and hemodynamic parameters. Clinically, blood pressure combined with central venous pressure (CVP) measurements is often used to guide fluid resuscitation.

Correction of acidosis is important during shock management, and bicarbonate may be administered intravenously as needed. Electrolyte imbalances should be monitored to prevent excessive or insufficient concentrations of electrolytes, which could lead to arrhythmias, reduced myocardial contractility, difficulty correcting acid-base imbalances, cellular edema, or dehydration.

Hemostasis

In cases of ongoing bleeding, difficulty maintaining stable blood volume, or persistent shock despite initial adequate fluid resuscitation, active bleeding is likely. The source of bleeding should be identified and managed promptly. For conditions such as liver or spleen rupture and acute active upper gastrointestinal bleeding, emphasis is placed on simultaneously restoring blood volume and preparing for emergency surgical intervention to achieve hemostasis.