Definition

Any tumor occurring within the bone or originating from various bone tissue components, whether primary, secondary, or metastatic, is collectively referred to as a bone tumor.

Classification

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the fifth edition of the classification of bone tumors.

Table 1 WHO classification of bone tumors (2020)

Epidemiology

Benign primary bone tumors are more common than malignant ones. Among benign tumors, osteochondromas and chondromas are frequently observed, while osteosarcomas and chondrosarcomas are more common among malignant tumors. The occurrence of bone tumors is age-related; for instance, osteosarcomas are more frequently seen in adolescents, whereas giant cell tumors of the bone primarily occur in adults. The anatomical location is also significant, as bone tumors often develop in areas of active growth in long bones, particularly the metaphysis, such as the distal femur, proximal tibia, and proximal humerus. The epiphysis is typically less affected.

Clinical Manifestations

Pain and Tenderness

Pain is the most prominent symptom in rapidly growing tumors. Benign tumors are often painless, though certain benign tumors, such as osteoid osteomas, can cause severe pain due to reactive bone growth. Malignant tumors almost invariably present with localized pain, which begins as intermittent and mild but progresses to persistent, intense, and nighttime pain accompanied by tenderness. Sudden aggravation of pain may indicate malignant transformation of a benign tumor or the presence of pathological fractures.

Local Mass and Swelling

Benign tumors often present as firm, painless masses that grow slowly and are usually detected incidentally. Rapidly enlarging swelling and masses are more commonly seen with malignant tumors. The presence of distended local blood vessels typically indicates malignancy, reflecting a rich blood supply to the tumor.

Functional Impairment and Compression Symptoms

Tumors near adjacent joints can cause pain and swelling, leading to impaired joint mobility. Spinal tumors, whether benign or malignant, can result in compression symptoms, including paralysis. Tumors with a rich blood supply may lead to increased local skin temperature and distended superficial veins. Tumors in the pelvis can cause obstructive symptoms in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems due to mechanical compression.

Pathological Fractures

Pathological fractures resulting from minor trauma may be the initial manifestation of certain bone tumors. This is also a common complication of malignant bone tumors and bone metastases. Tumors are often identified early due to the associated fracture, although the trauma itself does not induce tumor development.

Patients with advanced malignant bone tumors may exhibit systemic symptoms such as anemia, emaciation, loss of appetite, weight loss, and low-grade fever. Distant metastases are more often hematogenous, with occasional lymphatic spread.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bone tumors requires a combination of clinical, imaging, and pathological evaluations. Biochemical tests serve as an essential supplementary tool.

Imaging Examinations

X-ray Examination

X-rays can reveal the fundamental bone and soft tissue abnormalities. Tumor-related bone destruction is categorized as osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed. Some reactive bone formations associated with bone tumors may present as bone deposits, referred to clinically as tumor bone.

Benign bone tumors typically display clear boundaries and uniform density, often presenting as expansile lesions or exophytic growths. Bone destruction appears as unilocular or multilocular defects accompanied by punctate, ring-like, or patchy calcifications. Surrounding reactive bone sclerosis may be visible, and periosteal reactions are generally absent.

Malignant bone tumors often exhibit irregular lesions, such as "moth-eaten" or "punched-out" appearances, with uneven density and ill-defined boundaries. Periosteal elevation by tumors can produce new subperiosteal bone, forming a triangular opacity known as Codman’s triangle, which is commonly seen in osteosarcoma. Gradual periosteal elevation may create concentric or lamellar bone deposits, resembling an "onion skin" appearance commonly observed in Ewing’s sarcoma. Rapidly growing malignant tumors may outpace bone cortex expansion, leading to vascular invasion, with tumor bone and reactive bone radiating outward in a "sunburst" pattern. Some aggressive malignant tumors lack reactive bone, appearing as purely osteolytic defects on X-rays, demonstrating bone destruction. However, certain tumors, such as prostate cancer metastases, may trigger osteoblastic reactions.

CT and MRI Examinations

CT and MRI provide a basis for the presence and characterization of bone tumors. These imaging modalities allow clearer visualization of tumor extent, identification of invasion severity, and assessment of relationships with adjacent tissues. They are also instrumental in planning surgical strategies and evaluating treatment outcomes.

Other Diagnostic Methods

ECT (Emission Computed Tomography) can accurately delineate the extent of lesions and detect bone metastases weeks or even months earlier than other imaging modalities. Bone scans are valuable for the early identification of potential metastatic foci, reducing the risk of missed diagnoses. DSA (Digital Subtraction Angiography) can demonstrate the tumor's vascular supply, including main tumor vessels and newly formed neoplastic vasculature. Ultrasound examination can reveal soft tissue tumors and bone tumors protruding beyond the bone.

Pathological Examination

Histopathological examination is the only definitive method for diagnosing bone tumors. Based on the method of specimen collection, it can be classified into two types: needle biopsy and open biopsy. Needle biopsy involves a closed puncture using a specialized trocar biopsy needle and has the advantages of being simple, resulting in minimal bleeding, causing limited disruption of normal tissue compartments, reducing tumor cell dissemination, and minimizing pathological fractures. It is commonly used for lytic lesions in the spine and limbs. Open biopsy is further divided into incisional biopsy and excisional biopsy. Incisional biopsy disrupts the tumor's natural compartment and surrounding soft tissue barriers, increasing the area of tumor contamination. For smaller tumors, excisional biopsy is preferred.

Biochemical Tests

In most bone tumor cases, laboratory results are normal. However, when there is rapid bone destruction, such as with extensive lytic lesions, serum calcium levels may be elevated. Serum alkaline phosphatase, which reflects osteoblastic activity, is notably elevated in osteoblastic tumors like osteosarcoma.

Modern Biotechnology Testing

Advances in molecular and cellular biology have unveiled mechanisms related to clinical outcomes and prognosis. Genetic studies have identified chromosomal abnormalities in certain bone tumors, aiding in diagnosis, tumor classification, and more precise prediction of tumor behavior.

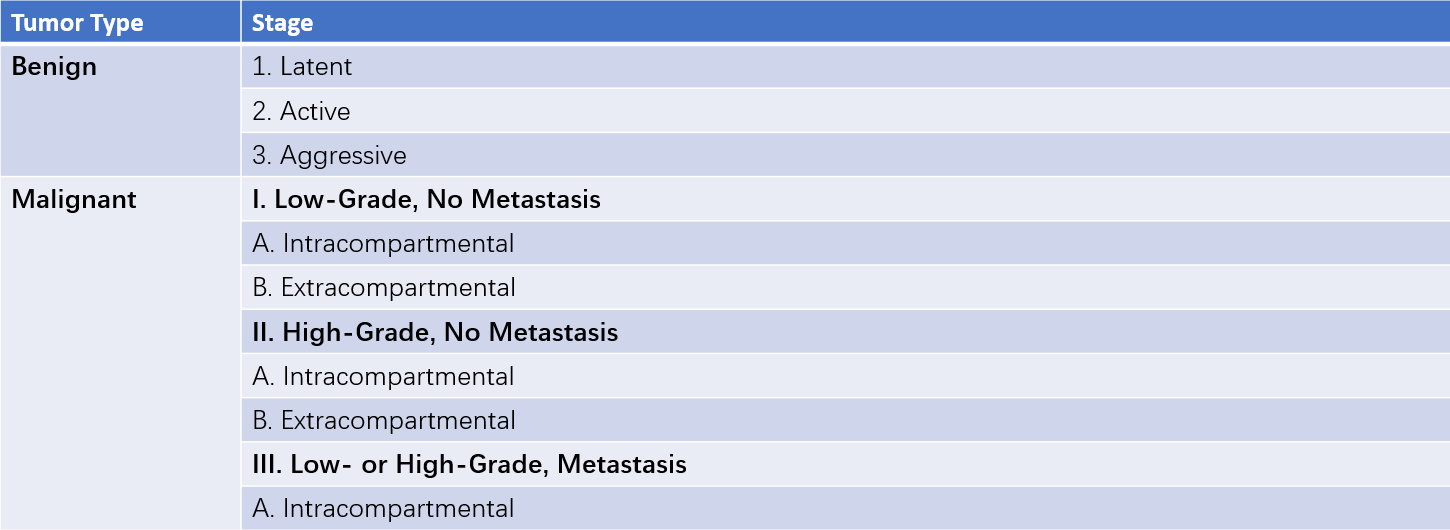

Surgical Staging (Enneking Staging System)

Pathological grading of tumors reflects their biological behavior and degree of aggressiveness. Using surgical staging to guide the treatment of bone tumors is a rational and effective approach. Surgical staging combines tumor grade (G), anatomical location (T), and regional or distant metastasis (M) to provide a comprehensive evaluation.

Surgical grading is determined based on clinical features, imaging findings, histological appearance, and laboratory results. It is divided into three grades:

G0 (Benign)

Histologically, the tumor exhibits benign cytological features, good differentiation, and a low to medium cell-to-matrix ratio. On X-ray, the tumor shows clear boundaries and is confined within a capsule or grows outward into soft tissue. Clinically, there is an intact capsule with no satellite lesions, no skip metastases, and extremely rare distant metastasis.

G1 (Low-Grade Malignant)

Histologically, the tumor displays moderate differentiation. On X-ray, the tumor breaches the capsule, causing cortical destruction and potentially extending beyond the capsule. Clinically, the tumor grows slowly, with no skip metastases observed and only occasional distant metastasis.

G2 (High-Grade Malignant)

Histologically, there is frequent nuclear mitosis, poor differentiation, and a high cell-to-matrix ratio. On X-ray, the tumor has indistinct margins and soft tissue involvement. Clinically, the tumor grows rapidly, presents with significant symptoms, and is associated with skip metastases as well as frequent local and distant metastases.

Tumor Anatomical Location (T)

The extent of tumor invasion is classified based on its proximity to natural compartments. Tumors can be intracapsular, intracompartmental, or extracompartmental:

- T0: Intracapsular.

- T1: Intracompartmental.

- T2: Extracompartmental.

Intracompartmental tumors are enclosed by natural barriers such as bone, fascia, synovial tissue, or periosteum. Extracompartmental tumors extend beyond these barriers due to tumor growth, fractures, bleeding, or surgical contamination, and this extracompartmental growth is a sign of tumor aggressiveness.

Metastasis (M)

Tumor metastasis is categorized based on the presence of regional or distant metastatic lesions:

- M0: No metastasis.

- M1: Presence of metastasis.

Treatment

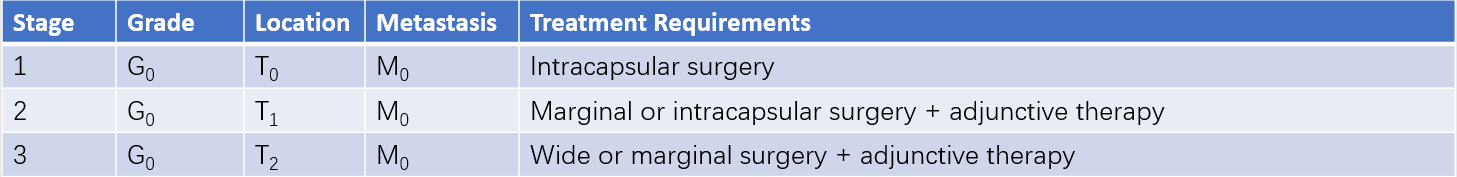

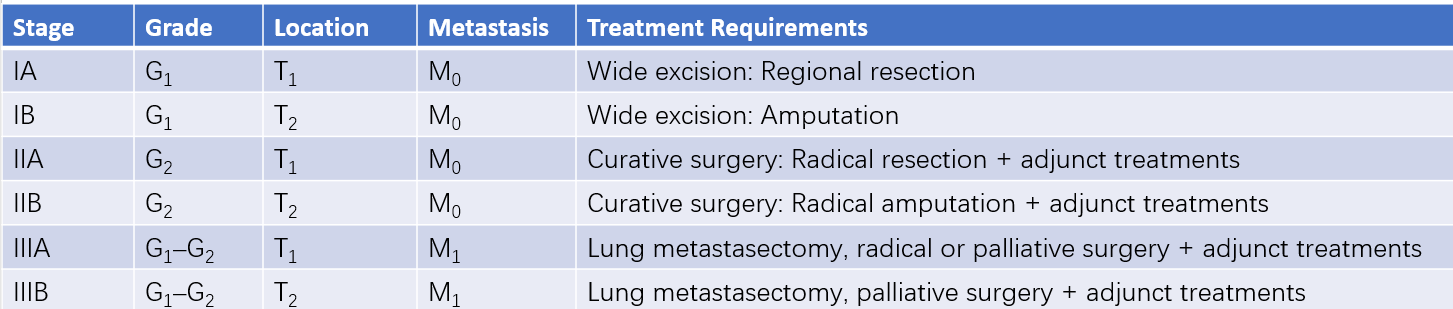

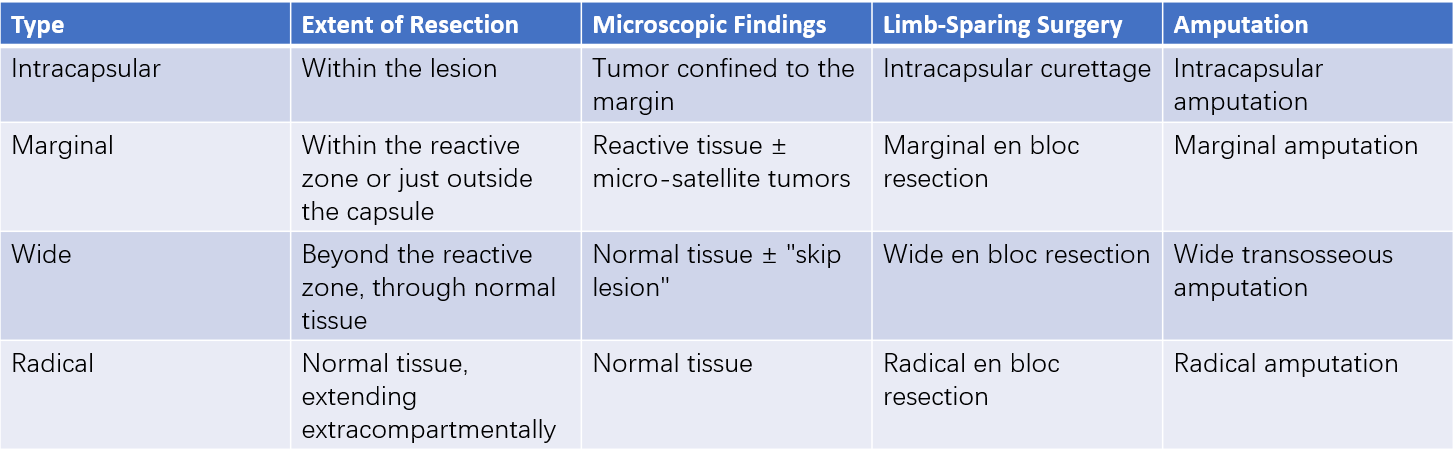

The treatment of bone tumors is guided by surgical staging. The selection of surgical boundaries and methods is based on the stage, aiming to achieve both tumor removal and limb preservation.

Table 2 Enneking staging for musculoskeletal tumors

Table 3 Treatment guidelines for benign bone tumors

Table 4 Treatment guidelines for malignant bone tumors

Table 5 Surgical margins

Surgical Treatment of Benign Bone Tumors

Curettage and Bone Grafting: This method is used for benign bone tumors and tumor-like lesions. During surgery, lesions are thoroughly curetted down to healthy bone tissue, and any residual tumor cells are destroyed using pharmacological or physical methods, followed by the placement of filler materials. Autologous bone grafts provide better healing but have limited availability, slower complete healing, and longer treatment duration. Other biologically active bone repair materials, such as allogeneic or artificial bone, are also widely used in clinical practice.

Excision of Exophytic Bone Tumors: Procedures such as osteochondroma resection fall under this category. The key to surgery lies in the complete removal of the tumor’s bone mass, cartilaginous cap, and periosteal cartilage membrane to prevent recurrence.

Surgical Treatment of Malignant Bone Tumors

Limb-Sparing Surgery

Advances in chemotherapy have significantly promoted the development of limb-sparing techniques. Research demonstrates that limb-sparing surgery has comparable survival rates and recurrence rates to amputation, with local recurrence rates between 5% and 10%. The key to surgery lies in achieving complete tumor removal with adequate surgical margins. Wide excision includes the tumor mass, capsule, reactive zone, and surrounding normal tissue. Tumor resection should occur within normal tissue, maintaining a bone-cutting plane of 3–5 cm from the tumor margin and a soft tissue excision margin of 1–5 cm beyond the reactive zone.

Indications for limb-sparing surgery include:

- Fully matured limbs.

- Stage IIA or chemotherapy-sensitive stage IIB tumors.

- Tumors not involving major neurovascular bundles and capable of complete removal.

- Recurrence and metastasis rates not exceeding those of amputation, with superior post-surgery limb functionality compared to artificial limbs.

- Patient preference for limb preservation.

Contraindications for limb-sparing surgery include:

- Tumor invasion of major nerves or blood vessels.

- Pathological fractures occurring before curative surgery or during preoperative chemotherapy, with tumor cells breaching natural barriers and contaminating adjacent normal tissues through hematomas.

- Poor soft tissue conditions surrounding the tumor, such as resection of major functional muscle groups, scarring from radiotherapy or repeated surgeries, or localized soft tissue infection.

- Incorrect incisional biopsies contaminating surrounding normal tissues or causing scarred, poorly elastic, and poorly vascularized skin.

Reconstruction following limb-sparing surgery can utilize four main approaches:

Inactivation and Reimplantation of Tumor Bone

Tumorous bone segments are excised, treated to remove tumors, and reimplanted in their original location to restore bone and joint integrity. However, this method has high rates of complications due to strong immune rejection triggered by inactivated proteins and is now rarely used.

Allograft Bone Transplantation

Bone segments stored in bone banks under extremely low temperatures are transplanted to the site of tumor removal and secured with internal fixation.

Prosthetic Replacement

This option primarily involves custom-made prostheses designed for tumors, including extendable prostheses, which differ from standard joint prostheses.

Allograft-Prosthesis Composites (APC)

This method combines allografts with prostheses to achieve functional reconstruction.

Amputation

Amputation remains an important and effective treatment method for patients with advanced-stage malignant bone tumors (stage IIB) who present late, exhibit extensive damage, or have not responded to other supportive treatments. The decision to perform an amputation must be made cautiously, with strict adherence to surgical indications while also considering the production and fitting of a prosthetic limb post-surgery.

Chemotherapy

The development of neoadjuvant chemotherapy concepts and principles has significantly improved the survival rates and limb preservation rates for patients with malignant bone tumors. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy during the perioperative period is now the standard protocol for malignant tumors such as osteosarcoma. Its administration is recommended at specialized centers for bone and soft tissue tumors. The pathological evaluation of preoperative chemotherapy effectiveness aids in guiding postoperative chemotherapy and predicting prognosis. Evidence of chemotherapy sensitivity includes the following: reduced or eliminated clinical pain symptoms, decreased tumor size, improved or normalized joint function, restored or normalized elevated alkaline phosphatase levels, reduced tumor size on imaging, clearer tumor contours, increased calcification or ossification within the lesion, and decreased or absent tumor neovascularization.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy has a strong inhibitory effect on the proliferative ability of malignant tumor cells. For certain tumors, preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy can help control lesions, alleviate pain, and reduce local recurrence rates. In cases where extensive lesions preclude surgery, radiotherapy alone may be utilized. Ewing's sarcoma is highly sensitive to radiotherapy, and radiotherapy can effectively control local lesions, either following chemotherapy or concurrently with it. Osteosarcoma is, however, less sensitive to radiotherapy.

Other Treatments

Embolization Therapy

Angiographic techniques are used for selective or super-selective embolization of tumor-feeding blood vessels. This method is applicable for reducing intraoperative bleeding by embolizing the main blood vessels supplying the tumor. Palliative embolization is also possible for inoperable malignant tumors to create conditions conducive to surgical tumor resection.

Combined Therapies

Intra-arterial infusion chemotherapy combined with embolization or radiotherapy post-embolization can achieve better outcomes. Hyperthermia-chemotherapy for malignant bone tumors provides a synergistic effect of heat and chemotherapy.

Emerging Treatments

Research in immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and biological therapy is highly active in the field of malignant tumor management.