Hip joint tuberculosis (coxotuberculosis) ranks third in prevalence among all bone and joint tuberculosis cases, following spinal tuberculosis and knee joint tuberculosis. It is more commonly observed in children and often presents unilaterally.

Pathology

In its early stages, hip joint tuberculosis can manifest as either synovial tuberculosis or osseous tuberculosis, with synovial tuberculosis being more common. Osseous tuberculosis typically occurs at the superior margin of the acetabulum or the peripheral portion of the femoral head, presenting as bony destruction, formation of sequestra, and cavitations, often accompanied by abscess formation. In advanced stages, cold abscesses and pathological dislocations can occur. Abscesses often protrude through the weak points of the anterior-medial aspect of the hip joint capsule and appear medial to the inguinal region or may extend posteriorly, forming gluteal abscesses that can break through the pelvic wall, resulting in pelvic abscesses.

Clinical Manifestations

The condition has a slow onset and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as low-grade fever, fatigue, lethargy, loss of appetite, weight loss, and anemia. The disease is typically unilateral, with pain as the initial symptom. In the early stages, the pain is mild and improves with rest. In children, this may present as nocturnal crying. Pediatric patients often report knee pain, which, if not carefully assessed, may delay diagnosis. As the pain intensifies, limping develops. In advanced stages, cold abscesses may appear in the medial side of the groin and gluteal regions, which may rupture to form chronic sinus tracts. Significant destruction of the femoral head often leads to pathological dislocation, predominantly posterior dislocation. Early tenderness may be present on the anterior side of the hip joint without obvious swelling, followed by atrophy of the quadriceps and gluteal muscles. The affected limb may develop flexion, abduction, and external rotation deformities in the early stages, which gradually progress to flexion, adduction, and internal rotation deformities as the disease advances. Hip joint ankylosis and limb length discrepancies are the most common findings.

The following clinical tests are useful for diagnosis:

Figure 4 Test

This test involves movements of hip joint flexion, abduction, and external rotation. A positive result is indicative of hip tuberculosis. The method involves having the patient lie supine on an examination table, flexing the affected leg, and placing the lateral malleolus over the unaffected side's patella. The examiner applies downward pressure on the knee of the affected side. The test is positive if the hip exhibits pain and the knee cannot touch the surface of the table. It should be noted that individual factors such as advanced age and obesity may affect this test, so a comparison with the contralateral side is necessary.

Figure 1 Figure 4 Test

(1) Negative; (2) Positive

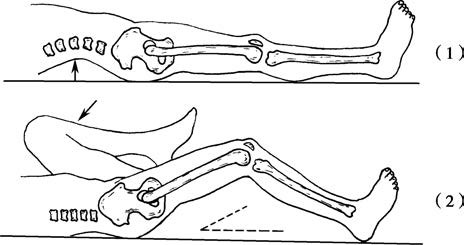

Hip Extension Test

This test is used to evaluate early hip joint tuberculosis in children. The method involves placing the child in a prone position. The examiner stabilizes the pelvis with one hand while lifting the lower limb by the ankle with the other hand until the pelvis begins to lift off the table. Performing the same test on the contralateral side facilitates comparison. The affected hip will exhibit restricted extension and resistance, with less extension range than the unaffected side. Normal hips can extend about 10 degrees.

Thomas Sign

This test is used to detect flexion deformities of the hip joint. The method involves having the patient lie supine on an examination table. The examiner flexes the hip and knee of the unaffected side fully, bringing the knee as close to the chest as possible, ensuring the lumbar lordosis is flattened and the lumbar spine is in contact with the table. If the affected leg cannot remain flat on the table, the test is positive. The angle between the affected leg and the table represents the degree of hip flexion deformity.

Figure 2 Thomas sign

Imaging Examinations

Plain X-ray imaging is critically important for diagnosing hip joint tuberculosis. Early lesions might not be apparent, making it necessary to obtain bilateral hip joint images for comparison. Localized osteoporosis is often the earliest radiological finding. If mild narrowing of the joint space is observed, further attention is warranted. In later stages, destructive arthritis is often accompanied by mild reactive sclerosis. In some cases, rapid and complete joint destruction, including cavitations and sequestra, may occur within weeks. Severe cases may cause near-total disappearance of the femoral head. Pathological dislocation may develop in advanced stages.

Figure 3 Plain X-ray of hip joint tuberculosis (1) and MRI (2)

CT and MRI provide additional assistance for early diagnosis. CT scans effectively reveal joint effusion, bone and soft tissue involvement, and subtle bony lesions that are not visible on plain X-rays. MRI can detect inflammatory infiltration within the bone, joint effusion, and cartilage destruction at earlier stages, with superior clarity compared to CT.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis is generally not difficult to establish based on the patient's history, symptoms, signs, laboratory, and imaging examinations. However, in the early stages, when lesions are mild, repeated examinations and careful observation are often required. Bilateral hip joint X-rays need to be compared to avoid misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis. Differentiation from the following conditions is necessary:

Transient Hip Synovitis

This condition is more common in children under 8 years of age. Symptoms include pain in the hip or knee joint, limping, or reluctance to walk. Hip joint movement is mildly restricted. A history of upper respiratory tract infection prior to onset is common. The condition usually resolves within a few weeks with bed rest and skin traction applied to the affected limb.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease (Osteochondritis of the Femoral Head)

Clinical findings may show varying degrees of restricted hip joint movement. Typical radiographic features include flattening and sclerosis of the femoral head, widening of the joint space, and, in later stages, fragmentation, necrosis, and cystic changes of the femoral head, along with shortening and thickening of the femoral neck. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is normal.

Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis (JRA)

Fever and elevated ESR are common in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, especially in the early stages when a single joint is involved, making differentiation difficult. However, JRA is characterized by multiple and symmetrical joint involvement, morning stiffness, and radiographic evidence of sacroiliac joint destruction. Short-term observation often facilitates differentiation.

Septic Arthritis

This condition has an acute onset and is associated with high fever. During the acute phase, symptoms of sepsis are often present, and pyogenic bacteria can be detected in blood and joint fluid cultures. Radiographic findings reveal rapid joint destruction, along with proliferative changes, while later stages may develop bony ankylosis. Differentiating chronic, mildly toxic pyogenic hip arthritis from hip tuberculosis with mixed infections can be challenging and usually requires bacterial culture of pus and biopsy for confirmation.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Early ankylosing spondylitis can be confused with sacroiliac joint tuberculosis. However, ankylosing spondylitis predominantly affects young adult males and frequently involves pain and restricted motion in the bilateral sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine. It is commonly bilateral. Positive HLA-B27 testing can aid in differentiation.

Treatment

Systemic Supportive Treatment

General condition improvement and enhancement of immune resistance are emphasized.

Pharmacological Treatment

Standardized use of anti-tuberculosis drugs is applied during active tuberculosis lesions and both pre- and post-surgical periods (as detailed in the general overview of the chapter).

Traction

Patients with severe hip pain, muscle spasms, or flexion deformities may undergo skin or skeletal traction to alleviate pain and correct deformities.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is reserved for cases where non-surgical treatment proves ineffective, with different surgical approaches tailored to the various stages of lesion development. Common procedures include synovectomy, lesion debridement, joint arthrodesis, osteotomy, and arthroplasty.

For isolated synovial tuberculosis, intra-articular injection of anti-tuberculosis drugs can be applied. If results are unsatisfactory, synovectomy is performed, followed by 3 weeks of immobilization in a functional position using skin traction and a “T-shaped shoe.” Isolated osseous tuberculosis should be treated with early lesion debridement to prevent extension into the joint, which may lead to joint tuberculosis.

For early total joint tuberculosis, lesion debridement should be performed promptly to preserve the joint if there are no contraindications to surgery.

For cases where the lesion has stabilized and tuberculosis has been completely controlled:

- Hip joint ankylosis with fibrous adhesions may result in minor movements triggering pain, making hip arthrodesis an appropriate treatment option.

- For significant flexion, adduction, or abduction deformities, subtrochanteric osteotomy is a suitable corrective procedure.

- To restore joint functionality, joint arthroplasty, such as total hip replacement, may also be an option. Since joint replacement surgery may activate dormant tuberculosis lesions, careful consideration is required after a confirmed, prolonged period of disease inactivity.