Spinal tuberculosis, also known as tuberculous spondylitis, accounts for the highest incidence among bone and joint tuberculosis cases, comprising more than 50% of cases. The vast majority of lesions occur in the vertebral bodies, with only 1%–2% involving the vertebral appendices. The vertebral body, mainly composed of cancellous bone, has end-arteries that make it prone to colonization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The lumbar spine is the most frequently affected site, followed by the thoracic and cervical spine. Both children and adults can be affected.

Pathology

Tuberculous lesions in the vertebral body are classified into two types: central type and marginal type.

Central-Type Vertebral Tuberculosis

This type is more common in children under the age of 10 and typically affects the thoracic spine. The disease progresses rapidly, with the entire vertebral body compressed into a wedge shape. It usually involves a single vertebra, though it may penetrate the intervertebral disc to affect adjacent vertebrae.

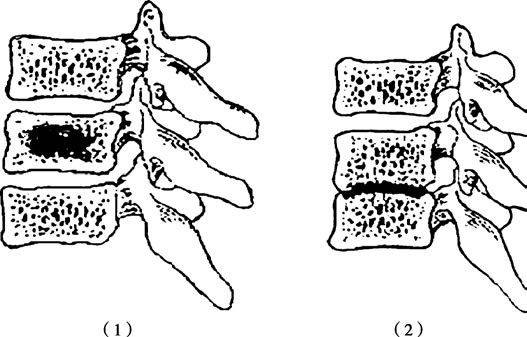

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of spinal tuberculosis pathology

(1) Central type: Vertebral body central bone destruction

(2) Marginal type: Intervertebral space narrowing

Marginal-Type Vertebral Tuberculosis

This type is more common in adults, with the lumbar spine being the most frequently affected site. The lesions are confined to the upper and lower edges of the vertebral bodies and quickly invade the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebrae. Destruction of the intervertebral disc is a characteristic feature, leading to narrowing of the intervertebral space.

Following vertebral destruction, cold abscesses may form and present in two ways:

Paravertebral Abscess

The pus collects beside the vertebral body, commonly in the anterior, posterior, or lateral spaces, with accumulation most frequently seen in bilateral and anterior areas. The pus lifts the periosteum and can spread along ligamentous planes both vertically upwards and downwards, causing bony erosions at the edges of multiple vertebral bodies. It can also extend posteriorly into the spinal canal, compressing the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Drifting Abscess

When the volume of a paravertebral abscess increases and pressure rises, the pus may rupture the periosteum and flow downward along fascial planes, resulting in abscesses at sites distant from the primary lesion. For example, a paravertebral abscess from the lower thoracic or lumbar lesions can collect within the psoas sheath, forming a psoas abscess. Superficial psoas abscesses are located beneath the anterior fascia of the psoas muscle and flow into the iliac fossa, forming an iliac fossa abscess. Deep psoas abscesses can penetrate the lumbar fascia into the lumbar triangle, forming lumbar triangle abscesses. The lumbar triangle is a potential space bordered by the posterior edge of the iliac crest, the lateral edge of the erector spinae, and the posterior edge of the internal oblique muscle. Psoas abscesses may further track along the psoas muscle to the lesser trochanter of the femur, forming deep inguinal abscesses. In some cases, the abscess can bypass the posterior aspect of the femur and spread to the lateral thigh or extend along the fascia lata to the area above the knee.

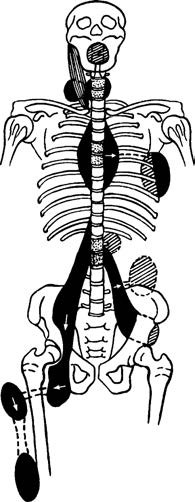

Figure 2 Pathways of cold abscess spread in spinal tuberculosis

Clinical Manifestations

Systemic Symptoms of Tuberculosis

The onset is insidious, with systemic symptoms such as low-grade fever in the afternoon, fatigue, weight loss, diaphoresis, loss of appetite, and anemia. In children, symptoms such as nocturnal crying, lethargy, or irritability may be observed.

Local Symptoms

The main local manifestations include pain, muscle spasms, restricted spinal mobility, and neurological dysfunction. Pain is often the earliest symptom. In the early stages, the pain is usually mild and not localized, but as the disease progresses, the pain becomes more fixed, typically at the spinous process or paraspinal region corresponding to the diseased vertebrae. Radiating pain may sometimes occur in the sensory distribution area of the corresponding nerve segment. Pain, along with instability of the affected vertebrae, leads to muscle spasms, resulting in the spine assuming a fixed, passive posture with significant movement restriction. Spinal deformities and neurological abnormalities may also be present. In some cases, paraplegia, kyphotic deformities, or sinus tracts are the primary presenting complaints.

Cervical Tuberculosis:

In addition to neck pain, symptoms may include numbness in the upper limbs due to nerve root irritation. Coughing or sneezing exacerbates the pain and numbness, and nerve root compression results in severe pain. In cases with a retropharyngeal abscess, breathing and swallowing may be compromised, and snoring may occur during sleep. In advanced cases, cold abscesses may manifest as neck masses.

Thoracic Tuberculosis

Back pain is a common symptom, although pain from lower thoracic lesions can sometimes manifest as lumbosacral pain. Kyphosis is frequently observed, and paraplegia is most commonly associated with thoracic tuberculosis.

Lumbar Tuberculosis

Patients often support their lumbar region with both hands while standing or walking, tilting the head and torso backward to shift the center of gravity and minimize pressure on the affected vertebrae. In advanced stages, psoas abscesses may form and appear as palpable or visually detectable masses in the lumbar triangle, iliac fossa, or inguinal region. These cold abscesses are an important reason for some patients to seek medical attention. Kyphosis in lumbar tuberculosis is usually mild and often requires careful physical examination for detection.

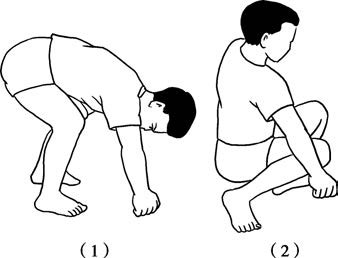

Pick-Up Test

While attempting to pick up an object from the ground, patients are unable to bend forward and must squat by flexing their knees and hips while keeping the lumbar spine extended, indicating a positive sign. In children, this can be examined by having the patient lie prone while the examiner lifts both feet and pelvis gently. If lumbar lesions are present, muscle spasms will cause the lumbar region to remain rigid, with the normal lordotic curve diminished.

Figure 3 Pick-up test

(1) Negative

(2) Positive

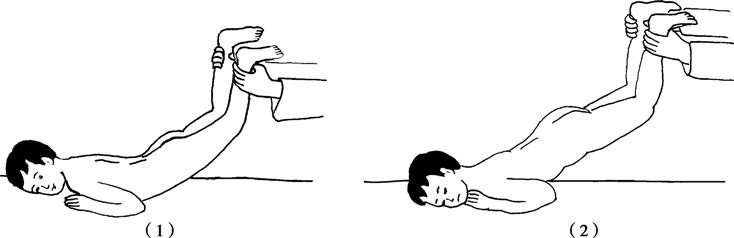

Figure 4 Pediatric spinal mobility assessment

(1) Normal

(2) Positive for disease

Imaging Examinations

X-Ray

The primary findings are bony destruction and narrowing of intervertebral spaces. In central-type tuberculosis, bony destruction is concentrated in the center of the vertebral body and is clearly visible on lateral radiographs. Vertebral compression often results in a wedge shape, with the anterior portion narrower than the posterior portion. In marginal-type tuberculosis, bony destruction is mainly located at the upper and lower margins of the vertebral body, with progressive narrowing of the intervertebral space and involvement of adjacent vertebrae. Scoliosis or kyphosis may be observed. Widening of the soft tissue opacity adjacent to the vertebrae (such as the psoas muscle) may also appear.

Figure 5 Radiographic presentation of marginal spinal tuberculosis: Bone destruction and intervertebral space narrowing

CT Scan

CT imaging clearly reveals the location of the lesion, the extent of bony destruction, and whether cavities or sequestra have formed. CT is particularly valuable for diagnosing psoas abscesses.

Figure 6 Spinal CT showing vertebral marginal destruction, sequestrum, and psoas abscess

MRI

Abnormal signals can be detected during the early inflammatory infiltration stage. MRI provides clear visualization of vertebral osteitis, intervertebral disc destruction, paravertebral abscesses, and compression or degeneration of the spinal cord and nerve roots. MRI is essential for the early diagnosis of spinal tuberculosis and is considered indispensable.

Figure 7 Spinal MRI demonstrating tuberculous lesion extending into spinal canal with spinal cord compression

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

A diagnosis can be established in typical cases based on the history, symptoms, signs, laboratory tests, and imaging findings. However, differential diagnosis with the following conditions is necessary:

Ankylosing Spondylitis

This is often associated with sacroiliitis, with primary symptoms of back pain. X-rays do not show bony destruction or sequestra but reveal the characteristic "bamboo spine" appearance. Thoracic involvement can lead to clinical manifestations such as restricted chest expansion. HLA-B27 testing is frequently positive.

Pyogenic Spondylitis

This has an acute onset, with high fever and significant pain, and progresses rapidly. Blood cultures in the early stages often identify the causative pathogen. X-rays show rapid progression and characteristic findings, aiding differentiation.

Lumbar Disc Herniation

This lacks systemic symptoms and presents with symptoms of nerve root compression in the lower limbs. X-rays show no bony destruction, while CT and MRI reveal herniated discs compressing the dural sac or nerve roots.

Spinal Tumors

These are commonly seen in elderly individuals, with progressively worsening pain. X-rays often show vertebral body destruction, frequently involving pedicles, while intervertebral space height remains normal. Paravertebral soft tissue masses are generally absent.

Eosinophilic Granuloma

This primarily affects children under 12 years of age and is more common in the thoracic spine. The entire vertebral body undergoes uniform flattening without changes in adjacent intervertebral disc spacing. Systemic symptoms of tuberculosis, such as low-grade fever or diaphoresis, are absent.

Degenerative Spinal Osteoarthritis

A condition associated with aging, it is characterized by narrowed intervertebral spaces and hypertrophic changes or sclerosis of adjacent articular processes. There are no signs of bony destruction or systemic symptoms.

Treatment

The goals of treatment for spinal tuberculosis are to thoroughly eliminate the lesions, relieve nerve compression, restore spinal stability, and correct spinal deformities. The majority of cases can achieve a cure through systemic supportive therapies and standardized anti-tuberculosis drug regimens. Surgical intervention is required in only a minority of cases.

Systemic Treatment

Supportive Treatment

Rest and nutritional enhancement are emphasized to manage the disease.

Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Therapy

Effective medication is the fundamental approach to eradicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis and curing spinal tuberculosis.

Local Treatment

Orthopedic Treatment

Methods such as spinal braces, plaster vests, or plaster beds are utilized to limit spinal movement, reduce pain, and prevent or correct deformities, thereby facilitating lesion recovery.

Abscess Aspiration or Drainage

This is applicable for large abscesses, with the option for local injection of anti-tuberculosis drugs to enhance local treatment efficacy.

Sinus Tract Dressing Changes

Appropriate care is provided for cases with sinus tracts.

Surgical Treatment

Indications for surgery include:

- Persistence of symptoms and progression of lesions despite standardized anti-tuberculosis therapy,

- Presence of large sequestra and cold abscesses within the lesion,

- Long-standing unhealed sinus tracts,

- Severe bone destruction and spinal instability,

- Symptoms of spinal cord or cauda equina compression, including paraplegia,

- Severe kyphotic deformities.

Principles of surgical treatment include:

- Preoperative administration of standardized anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy for 2–4 weeks to control mixed infections.

- Thorough intraoperative lesion debridement, relief of spinal cord and nerve compression, restoration of spinal stability, and correction of spinal deformities.

- Postoperative continuation and completion of the full course of standardized chemotherapy.

In cases where tuberculosis has been cured and surgery is performed solely for deformity correction, administration of anti-tuberculosis drugs may not be necessary.