Pyogenic arthritis refers to a purulent infection within a joint, most commonly observed in children and primarily affecting the hip and knee joints.

Etiology

The most frequent causative pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, accounting for approximately 85% of cases. Other pathogens include Group B Streptococcus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and enterobacteria. Bacteria can enter the joint through several pathways:

- Hematogenous infection, where bacteria from purulent foci in other parts of the body spread to the joint via the bloodstream.

- Direct spread from adjacent purulent foci, such as osteomyelitis of the femoral head or iliac bone extending into the hip joint.

- Open joint injuries that lead to infection.

- Iatrogenic infections, such as those occurring after joint surgery or intra-articular injections. This discussion focuses primarily on hematogenous pyogenic arthritis.

Pathology

The pathological progression of pyogenic arthritis can be divided into three stages. The progression may sometimes be slow, while in other cases it develops rapidly, making differentiation difficult.

Serous Exudative Stage

In this stage, bacteria entering the joint cavity cause marked vascular congestion and edema of the synovium, along with infiltration of white blood cells and serous exudation. The exudate contains abundant white blood cells, but the articular cartilage remains intact. If treatment is prompt, the exudate may be completely absorbed without leaving any functional impairment in the joint. At this stage, the pathological changes are reversible.

Serofibrinous Exudative Stage

As the condition progresses, the exudate becomes more abundant, turbid, and viscous, containing numerous inflammatory cells, pus cells, and fibrin. Enzymes present in the synovial fluid exacerbate synovitis, and vascular permeability is significantly increased. Large amounts of fibrin appear in the synovial fluid and deposit on the cartilage surface, disrupting cartilage metabolism. White blood cells release abundant lysosomal enzymes, which contribute to the breakdown, fragmentation, and collapse of the cartilage matrix. This leads to varying degrees of cartilage destruction. By this stage, some changes may become irreversible, and even after inflammation subsides, joint adhesions and functional impairment remain.

Purulent Exudative Stage

At this stage, the exudate in the joint becomes distinctly purulent, with widespread cartilage destruction. The inflammation extends to the subchondral bone, and cellulitis may develop in the surrounding tissue. These pathological changes are irreversible, leading to severe adhesions or fibrous or bony ankylosis after repair, significantly impairing joint function.

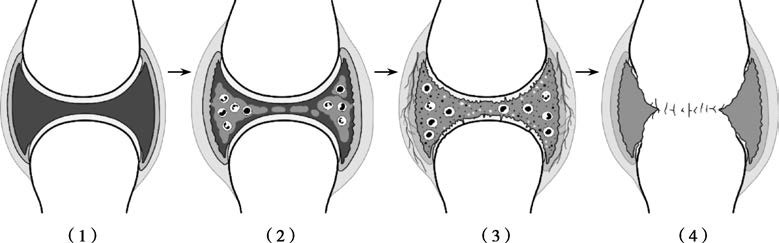

Figure 1 Diagram illustrating the pathological changes of pyogenic arthritis in the knee joint

(1) Normal (2) Serous exudation (3) Cartilage destruction (4) Bony ankylosis of the joint

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of pyogenic arthritis is typically acute, presenting with symptoms such as chills and high fever, with temperatures exceeding 39°C. In children, delirium and coma may occur. Rapid onset of pain and functional impairment is observed in the affected joint, and due to severe pain, patients often resist any physical examination. Superficial joints like the knee or elbow exhibit prominent signs of redness, swelling, heat, and pain. The joint is often held in a semi-flexed position to relax the joint capsule, increase joint cavity volume, and alleviate pain. In cases of knee effusion, localized swelling is most prominent, and suprapatellar pouch swelling may be observed, with a positive patellar tap test. When tension is excessive, the patellar tap test may be inconclusive. The hip joint, surrounded by extensive musculature, often lacks visible redness, swelling, or heat, and the limb is commonly held in a position of flexion, external rotation, and abduction. In some cases, referred pain may present as knee joint pain. The thick and resilient joint capsule in the hip makes purulent fluid less likely to break into soft tissues; however, once this occurs, cellulitis becomes apparent. In deep abscesses that rupture the skin, sinus tracts may form, and both systemic and local inflammatory symptoms rapidly subside, marking the transition to a chronic phase of the disease.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Peripheral blood tests reveal elevated leukocyte counts and a higher proportion of neutrophils, along with increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels. Blood cultures obtained during febrile episodes may identify the causative pathogen, with subsequent antimicrobial susceptibility testing guiding treatment. Joint fluid aspiration reveals varying appearances of synovial fluid depending on the pathological stage: clear (serous), cloudy (serofibrinous), or yellow-white (purulent). Microscopic examination identifies abundant white blood cells (early stage) or pus cells (late stage), while Gram staining may show clusters of Gram-positive cocci. The aspirate is also subjected to bacterial culture and drug sensitivity testing.

Imaging Studies

Early X-rays typically reveal soft tissue swelling around the joint. Lateral views of the knee joint may show notable suprapatellar pouch swelling and widened joint spaces. As the disease progresses, signs of bone demineralization appear, and severe cases exhibit joint space narrowing due to cartilage destruction, with subchondral bone destruction appearing "moth-eaten." In later stages, joint contractures, severe joint space narrowing, or bony ankylosis with trabecular bridging may be observed.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis is generally not difficult and is based on systemic and local symptoms, signs, as well as laboratory tests. X-ray findings appear relatively late and are not reliable for early diagnosis. Joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis are valuable for early diagnosis. Peripheral blood and joint fluid bacterial cultures, along with antimicrobial sensitivity testing, help identify the causative pathogen and guide the selection of antibiotics.

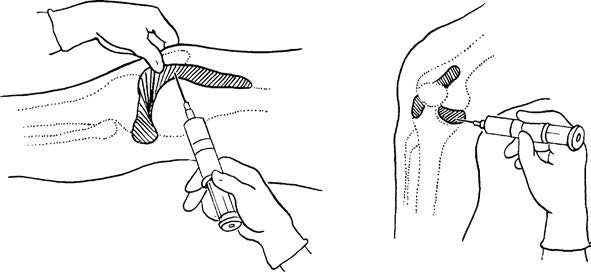

Figure 2 Schematic diagram of knee joint aspiration

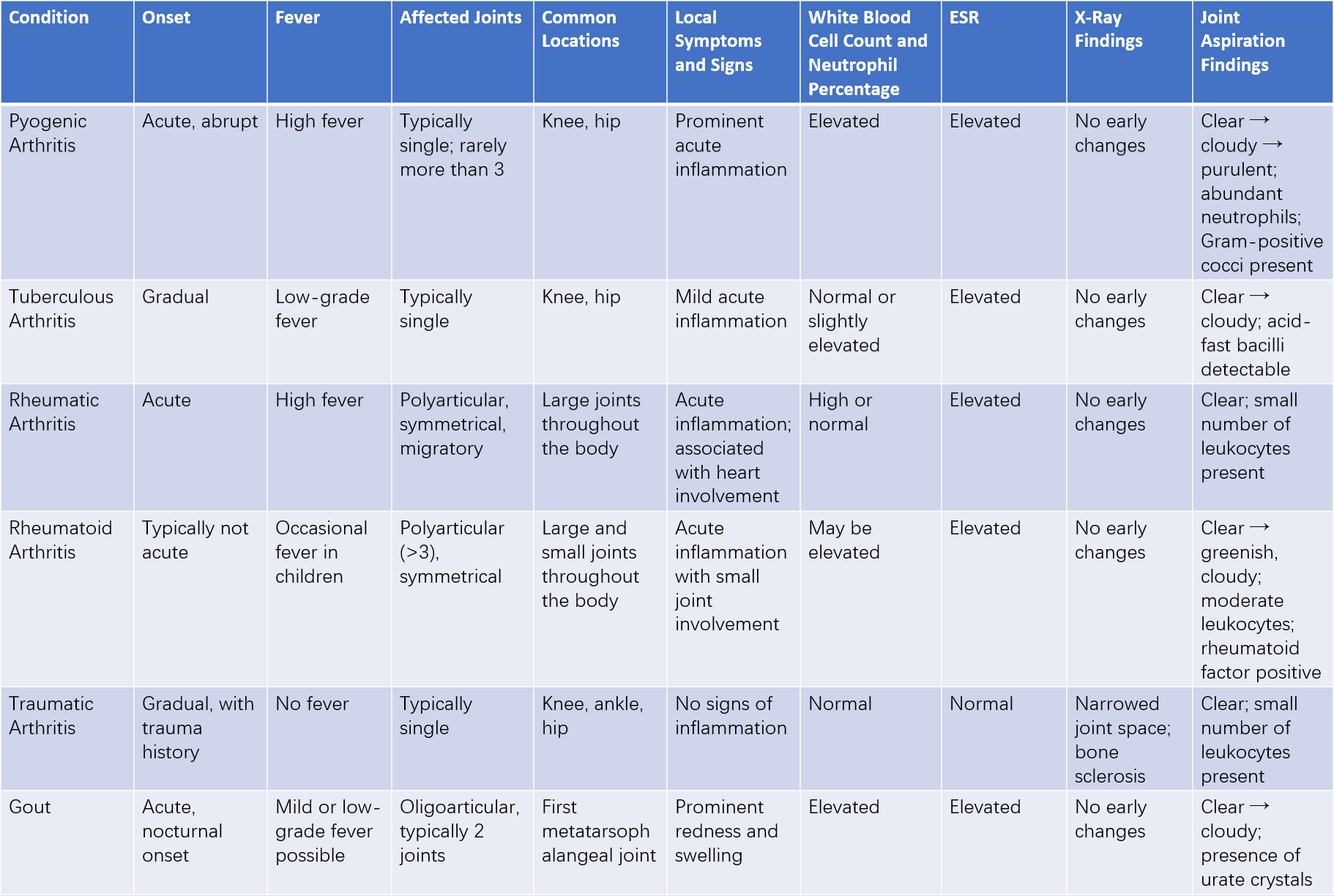

Key conditions requiring differential diagnosis are summarized in the table below.

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of pyogenic arthritis

Treatment

Systemic Treatment

Early-stage management involves the intravenous administration of sufficient and appropriate antibiotics for an adequate duration. Concurrently, systemic supportive therapies are implemented.

Local Treatment

Different pathological stages call for different therapeutic approaches.

Intra-articular Antibiotic Injection

This is suitable for the serous exudative stage and the serofibrinous exudative stage. When there is joint effusion without suppuration, the effusion is removed through aspiration, followed by the injection of saline containing antibiotics. Repeated irrigation and aspiration are performed 1 to 2 times daily until the synovial fluid appears clear and microscopy results are normal. If the joint fluid becomes clearer and local symptoms improve, treatment is considered effective and can be continued until the joint effusion resolves completely and body temperature normalizes. However, if the aspirated fluid becomes more turbid or even purulent, the current approach is deemed ineffective, and alternative interventions are required.

Continuous Joint Lavage

This approach is suitable for the serofibrinous exudative stage in large superficial joints such as the knee. Two plastic or silicone tubes are percutaneously inserted and left in place within the joint cavity: one serves as an irrigation catheter, and the other as a drainage tube. The tubes are secured at the entry points to prevent dislodgment. Antibiotic solutions (2,000–3,000 ml per day) are continuously infused through the irrigation catheter. Lavage is discontinued once the drainage fluid turns clear and cultures show no bacterial growth, but the drainage tube remains in place. The tube is eventually removed after resolution of local symptoms and normalization of body temperature and blood work, with no drainage observed for three consecutive days.

Arthroscopic Surgery

This is appropriate for the serofibrinous exudative stage and the purulent exudative stage. Arthroscopy allows the removal of pus and fibrinous exudates and thorough irrigation of the joint cavity. Irrigation and drainage catheters are placed for postoperative continuous lavage and drainage.

Open Joint Drainage

This is indicated for the serofibrinous exudative stage and the purulent exudative stage. The procedure involves direct visualization for debridement, followed by continuous postoperative irrigation and drainage. However, due to the widespread use of arthroscopic techniques, this method has become less commonly applied.

Immobilization of the Affected Limb

Skin traction or plaster fixation is used to position the joint in a functional alignment. This helps alleviate pain, control the spread of infection, and prevent contracture deformities.

Corrective Surgery in Later Stages

In cases of pathological dislocation, corrective surgery may be considered. For hip joint ankylosis, total hip arthroplasty can be performed.

Figure 3 Late-stage ankylosis due to pyogenic arthritis of the hip joint, undergoing total hip arthroplasty