Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis is a progression of inadequately controlled acute suppurative osteomyelitis. Systemic symptoms mostly disappear, and symptoms are typically limited to local manifestations. Acute systemic symptoms may appear in cases of impaired drainage. The disease can recur repeatedly and persist for several years or decades without resolution.

Pathology

The primary pathological features include:

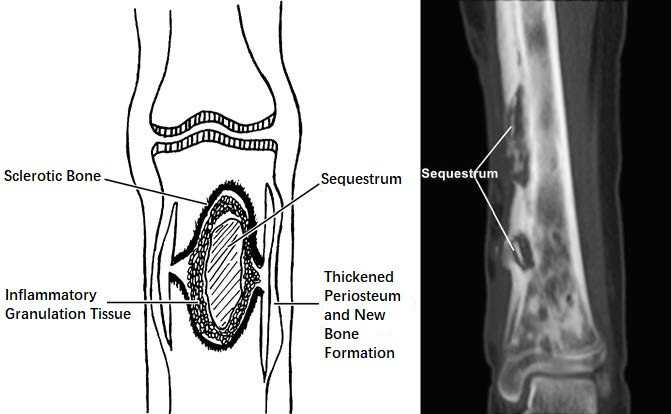

- Sequestra and Dead Spaces: The sequestra and dead spaces are filled with necrotic granulation tissue and pus, with the sequestra immersed within, forming a persistent source of infection.

- Fibrous Scarring: Recurrent acute inflammations lead to fibrous scarring within soft tissues, resulting in poor local blood supply and diminished repair capacity.

- Involucrum Formation: The periosteum grows repeatedly, forming lamellar bone (involucrum) around the lesion. The involucrum contains multiple openings referred to as cloacae, which connect internally to the dead space and externally to sinus tracts.

- Purulent Discharge from Sinus Tracts: After pus drains through the sinus opening, inflammation may temporarily subside and the sinus opening closes. The overlying skin becomes attenuated and highly prone to rupture. When pus reaccumulates in the dead space, it may rupture again. Through such recurrent cycles, the epidermis invaginates deep into the sinus tract. The sinus wall develops extensive inflammatory fibrous scarring, with hyperpigmentation of the perisinus skin. In rare cases, squamous cell carcinoma may develop.

Clinical Manifestations

During the quiescent phase of the disease, symptoms are often absent. Some cases may present with localized swelling, rough skin texture, pigmentation, limb thickening and deformation, and muscle atrophy in the affected area. A minority of cases may exhibit limb shortening, joint contracture, or stiffness. If the sinus tract remains open, small pieces of necrotic bone may occasionally be expelled. During acute exacerbations, systemic toxic symptoms may appear, along with localized pain, skin redness, warmth, increased swelling, and significant tenderness. Previously closed sinus tracts may rupture again, with the discharge of pus and necrotic bone.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory tests typically reveal no specific abnormalities. X-ray imaging may show thickening of the periosteum and the cortical bone, as well as increased bone density. The most characteristic finding is sequestra with increased density and irregular margins, surrounded by a radiolucent area representing the dead space. Newly formed bone forms a sclerotic involucrum that encloses the sequestra. The shaft of the bone may appear thickened, irregular, or even deformed, with uneven cortical density, loss of normal trabecular organization, and narrowing or obliteration of the medullary cavity.

Figure 1 Schematic diagram and x-ray findings of chronic osteomyelitis lesions

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of this condition is relatively straightforward based on the patient's medical history, symptoms, and physical findings, particularly in cases where necrotic bone has been discharged from a sinus tract. X-ray imaging can confirm the presence of sequestra and clarify their shape, number, size, location, and the extent of involucrum formation.

Treatment

The primary approach is surgical treatment. The main principles are the removal of necrotic bone and infected granulation tissue, elimination of dead spaces, excision of sinus tracts, and eradication of the infection source.

Indications for Surgery

Surgery is indicated in cases of sequestra formation, dead spaces, and draining sinus tracts.

Contraindications for Surgery

Surgical debridement is not advisable during acute exacerbations of chronic osteomyelitis, and antibiotic therapy is prioritized. Incision and drainage are recommended in cases of abscess formation.

In cases of large sequestra where the involucrum has not yet formed fully, early surgery to remove large necrotic bone may result in extensive bone defects and an increased risk of pathological fractures.

Surgical Methods

Preoperatively, bacterial cultures and drug sensitivity tests should be performed using sinus tract discharge. Systemic antibiotic therapy should be initiated two days before surgery to ensure sufficient antibiotic levels in the target tissues.

Lesion Debridement

All sequestra, pus, necrotic tissue, granulation tissue, and scar tissue are removed until healthy tissue with active bleeding is exposed. To completely excise the sinus tract, a small catheter can be inserted into the sinus tract the night before surgery, with methylene blue injected as a marker. For cases where the medullary cavity is occluded, hardened bone should be drilled to reopen the medullary cavity, restoring blood supply.

Elimination of Dead Space

Saucerization Procedure (Orr Procedure)

The edges of the bony dead space are beveled to create a large-mouthed, bowl-shaped cavity. Surrounding soft tissue enters the cavity to fill the dead space.

Muscle Flap Filling

Muscle flaps or vascularized muscle transfers from nearby areas are used to fill the dead space. The abundant blood supply of the muscle improves local bone circulation after healing with the cavity walls.

Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Bead Chains

Beads made from bone cement containing sensitive antibiotics are placed in the dead space. As granulation tissue grows to fill the cavity, the beads are gradually removed. In recent years, new degradable biological materials have been introduced as substitutes for bone cement.

Irrigation and Drainage

Irrigation and drainage tubes are placed in the dead space to allow continuous irrigation and complete drainage postoperatively.

Segmental Excision

In cases involving non-critical areas, such as the fibula, ribs, or iliac crest, the affected segments can be excised entirely.

Wound Closure

Primary closure of the wound is pursued when possible. However, excision of sinus tracts often results in skin defects, making closure difficult. For larger wounds, dressings that transition from wet-to-dry are applied and changed every 2–3 days. Once granulation tissue has adequately filled the wound, split-thickness skin grafts are applied. Local musculocutaneous flaps, pedicle flaps, musculocutaneous transfers, or free flaps with vascular anastomoses can also be utilized for wound closure.