Lumbar disc herniation refers to the pathological condition where, following degenerative changes in the lumbar intervertebral disc, external forces cause partial or complete rupture of the annulus fibrosus. This may result in the nucleus pulposus, cartilage endplate, or both protruding outward, leading to stimulation or compression of the sinuvertebral nerve and nerve roots, with low back and leg pain being the primary symptoms. Lumbar disc herniation is a common and frequently occurring condition in orthopedics and is the most common cause of low back and leg pain.

Etiology

Disc Degeneration as the Fundamental Cause

The lumbar intervertebral disc bears significant stress during spinal motion and loading. With aging, it undergoes degeneration, characterized by a gradual reduction in the water content of the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus, loss of elasticity in the nucleus pulposus, and the development of cracks in the annulus fibrosus. On this degenerative foundation, cumulative wear and external forces can cause disc rupture, resulting in the posterior protrusion of the nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosus, or even endplate, which can compress nerves in severe cases and produce symptoms.

Injury

Cumulative trauma is a primary cause of intervertebral disc degeneration. Repeated forward bending, twisting, and other movements are particularly likely to cause disc injury, creating a correlation between this condition and certain occupations. For instance, drivers subjected to prolonged sitting and vibrations, as well as individuals engaged in heavy physical labor, are prone to early disc degeneration due to excessive loading. Acute trauma can also act as a triggering factor for disc herniation.

Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the entire ligamentous system becomes relaxed, and the lumbosacral region experiences greater stress than usual, which increases the risk of disc herniation.

Genetic Factors

Approximately 32% of patients under the age of 20 with this condition have a positive family history.

Developmental Abnormalities

Congenital abnormalities involving the lumbosacral region, such as sacralization of the lumbar vertebrae, lumbarization of the sacral vertebrae, and asymmetric facet joints, expose the lower lumbar spine to abnormal stress, thereby increasing the risk of disc damage.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The intervertebral disc consists of the nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosus, and cartilage endplate. Given that the disc supports the weight of the trunk and upper limbs, it is prone to wear and tear during daily activities and labor. The disc has limited blood supply, primarily relying on nutrient diffusion through the cartilage endplate, making it highly susceptible to degeneration.

The biochemical composition of the disc includes collagen, proteoglycans, elastin, and water. During disc degeneration, the proportion of type I collagen increases while type II collagen decreases, and type I collagen may appear within the nucleus pulposus. Furthermore, the levels of proteoglycans decline, elastin concentration significantly decreases, elastic fiber density reduces, and structural defects such as cracks and irregular cavities emerge. The water content of the nucleus pulposus declines from 90% at birth to 70% at age 30 and remains relatively stable in old age.

There is still some debate regarding the mechanism through which disc herniation causes low back and leg pain. Two widely accepted theories include:

- Mechanical Compression: It is generally believed that the acute mechanical compression of the nerve root by herniated nucleus pulposus entering the spinal canal produces symptoms of low back and leg pain, with the size of the herniation directly affecting pain intensity. However, this theory does not explain all clinical phenomena.

- Inflammatory Response: The herniated nucleus pulposus, acting as a biochemical and immunological stimulant, may trigger inflammatory responses in the surrounding tissues and nerve roots, which could account for the patient's symptoms.

Several classification methods exist for lumbar disc herniation, each with its own criteria and focus. Based on the extent of herniation, imaging characteristics, and corresponding treatment approaches, the condition can be categorized as follows:

- Protrusion Type: The annulus fibrosus experiences partial rupture but remains intact on the surface. The nucleus pulposus shows localized elevation into the spinal canal, with a smooth surface. Most cases in this category respond well to conservative treatment.

- Extrusion Type: The annulus fibrosus is completely ruptured, and the nucleus pulposus extends into the spinal canal, while the posterior longitudinal ligament remains intact. Some cases in this category require surgical treatment.

- Sequestration Type: The nucleus pulposus breaches the posterior longitudinal ligament, appearing cauliflower-like, but its base remains within the intervertebral space. Surgical intervention is necessary.

- Free Fragment Type: Large fragments of the nucleus pulposus penetrate the annulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament, completely entering the spinal canal and detaching from the original disc. Surgical treatment is required.

- Schmorl's Node and Transosseous Extrusion Type: The former refers to the nucleus pulposus penetrating into the cancellous bone of the vertebral body through congenital or acquired fissures in the upper or lower cartilage endplate. The latter refers to the nucleus pulposus extending in the direction of the anterior longitudinal ligament through vascular channels between the endplate and vertebral body, forming free osseous fragments at the anterior edge of the vertebral body. Clinically, these two types usually lack neurological symptoms and do not require surgical intervention.

Clinical Manifestations

Lumbar disc herniation commonly occurs in patients aged 20 to 50, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately (4–6):1. Many patients have a history of performing work that requires bending or prolonged sitting. The initial episode often occurs during activities involving partial forward flexion while lifting or sudden twisting of the lumbar spine.

Symptoms

Low Back Pain

The majority of patients with lumbar disc herniation experience low back pain. This pain can precede, coincide with, or follow leg pain. The occurrence of low back pain is caused by the herniated disc irritating the sinuvertebral nerve fibers within the outer annulus fibrosus and posterior longitudinal ligament.

Sciatica

Sciatica is commonly associated with lumbar disc herniation since approximately 95% of cases involve the L4–L5 and L5–S1 intervertebral spaces. The pain typically develops gradually and radiates from the buttocks, down the posterolateral thigh, lateral calf, and to the heel or dorsum of the foot. Some patients adopt postures, such as leaning forward while walking or curling up with flexed hips and knees when lying down, to alleviate pain by reducing tension on the sciatic nerve. Sciatica may intensify when sneezing or coughing due to increased abdominal pressure. In cases of herniation at higher lumbar levels (e.g., L2–L3 or L3–L4), the protruding disc can compress the corresponding upper lumbar nerve roots, resulting in pain in the anteromedial thigh or groin region.

Cauda Equina Syndrome

Central lumbar disc herniation can compress the cauda equina, leading to dysfunction in bowel and bladder control and sensory disturbances in the perineal area (saddle anesthesia). Acute onset of such symptoms is considered an indication for emergency surgery.

Signs

Lumbar Scoliosis

Lumbar scoliosis is a compensatory postural deformity aimed at reducing pain and has diagnostic significance. When the protruded nucleus pulposus presses on the shoulder of the nerve root, patients bend their upper body toward the healthy side, causing the lumbar spine to curve toward the symptomatic side, thereby relieving nerve root compression. Conversely, when the nucleus pulposus presses on the axillary part of the nerve root, the upper body tilts toward the symptomatic side, and the lumbar spine curves toward the healthy side to alleviate pain.

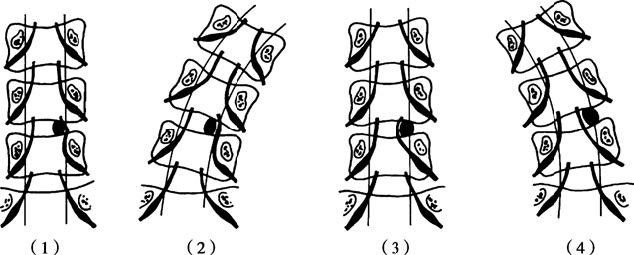

Figure 1 Relationship between postural spinal scoliosis and relief of nerve root compression

(1) When the disc herniation is located at the axillary region of the nerve root

(2) Nerve root pressure can be relieved by curving the spine toward the healthy side

(3) When the disc herniation is located at the lateral region of the nerve root

(4) Nerve root pressure can be relieved by curving the spine toward the affected side

Limited Lumbar Motion

Most patients exhibit varying degrees of restricted lumbar movement, with forward flexion being most notably limited. This restriction occurs because forward flexion causes the nucleus pulposus to shift further backward, increasing tension on the compressed nerve root.

Tenderness and Paraspinal Muscle Spasms

Tenderness is often present at the interspinous space of the affected intervertebral disc, and palpation 1 cm lateral to the spinous process may elicit radiating pain along the sciatic nerve. Approximately one-third of patients exhibit spasms in the lumbar paraspinal muscles, which cause the lumbar spine to remain in a fixed, forced posture.

Straight-Leg Raise Test and Enhancement Test

In the straight-leg raise test, the patient lies supine with the knee extended, and the affected leg is passively raised. Normally, nerve roots can slide by about 4 mm, and discomfort in the popliteal fossa is felt only when the leg is raised to 60–70°. In patients with lumbar disc herniation, nerve root compression or adhesion reduces or eliminates this sliding motion, and sciatic pain appears when the leg is raised to less than 60°, indicating a positive test result. During a positive straight-leg raise test, lowering the leg until radiating pain subsides, and then passively dorsiflexing the ankle to stretch the sciatic nerve, can reproduce the radiating pain, indicating a positive enhancement test.

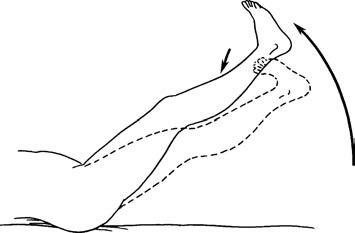

Figure 2 Straight-leg raise test (solid line) and reinforced test (dashed line)

Neurological Signs

Sensory Abnormalities

Most patients exhibit sensory abnormalities. Compression of the L5 nerve root may result in diminished pain and tactile sensitivity on the lateral calf and dorsum of the foot, while compression of the S1 nerve root may lead to reduced pain and tactile sensitivity around the lateral malleolus and lateral aspect of the foot.

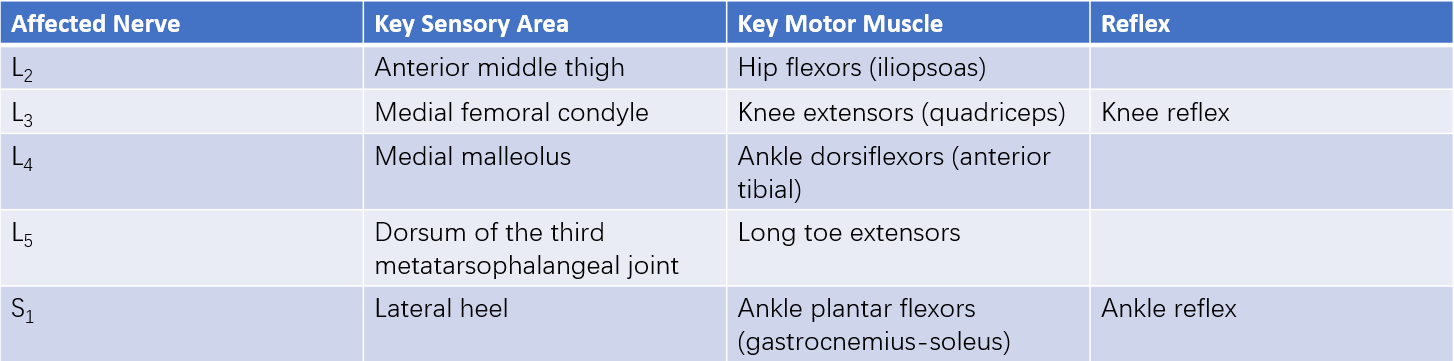

Table 1 Neurological localization of lumbar nerve root involvement

Muscle Weakness

Severe or prolonged nerve compression may lead to muscle weakness. L5 nerve root involvement may weaken the toe extensor muscles, while S1 nerve root compression may weaken the plantar flexor muscles.

Reflex Abnormalities

Compression of different nerve roots often results in corresponding reflex changes. Diminished or absent ankle reflexes suggest S1 nerve root compression. Compression of the S3–S5 cauda equina nerves may lead to reduced anal sphincter tone and weakened or absent anal reflexes.

Imaging and Other Examinations

X-ray Radiography

X-ray radiography is commonly used as part of routine assessment. Standard anteroposterior and lateral views of the lumbar spine are typically taken. In cases of suspected spinal instability, flexion-extension dynamic views and oblique views may also be taken. X-rays may yield completely normal findings in patients with lumbar disc herniation, but some positive findings may also be present. Anteroposterior views may reveal lumbar scoliosis, while lateral views may show a reduction or disappearance of the physiologic lumbar lordosis and narrowing of intervertebral disc spaces. Signs of degeneration, such as annulus fibrosus calcification, osteophyte formation, hypertrophy, and sclerosis of the facet joints, may also be observed.

Myelography

Techniques such as spinal myelography, epidurography, and discography may indirectly indicate the presence and extent of disc herniation. However, due to their invasive nature, potential complications, and technical complexity, these methods are now rarely employed and only considered when other diagnostic modalities do not provide clear information.

CT Scan

CT imaging provides detailed visualization of bony structures of the spine. In patients with lumbar disc herniation, CT may reveal posterior deformation of the intervertebral disc, compression or deformation of the dural sac, displacement of epidural fat, soft tissue density shadows in the epidural space, and displacement of the nerve root sheath. CT can also aid in evaluating the condition of the facet joints and ligamentum flavum.

Figure 3 Axial CT image showing lumbar disc herniation

MRI

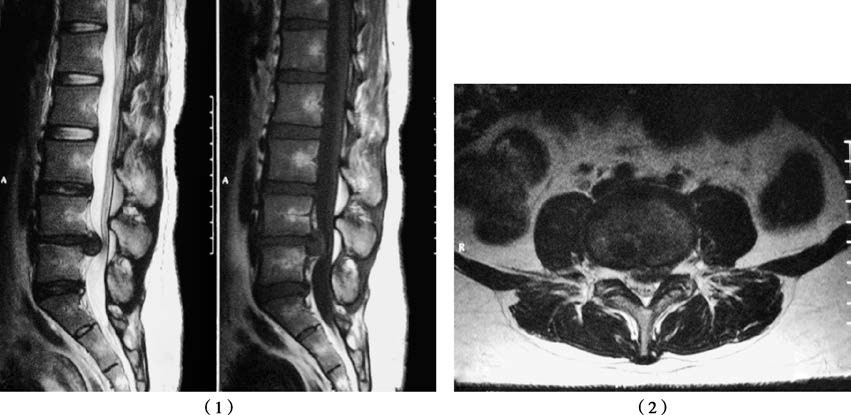

MRI offers clear imaging of anatomical structures and is highly beneficial for diagnosing lumbar disc herniation. MRI enables comprehensive observation of intervertebral disc degeneration, assessment of the degree and location of nucleus pulposus herniation, and differentiation from other space-occupying lesions in the spinal canal. For accurate localization, sagittal and axial views must be compared during interpretation.

Figure 4 MRI of L4–L5 disc herniation

Sagittal view (1) and axial view (2) showing a significant disc herniation at L4–L5 compressing the dural sac.

Others

Electrophysiological studies, such as electromyography, can assist in the diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation and help identify the specific segment of nerve root damage.

Diagnosis

A preliminary diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation can generally be established in typical patients based on their medical history, symptoms, clinical signs, and evidence of disc degeneration on corresponding intervertebral levels in plain X-rays. Accurate assessment of the affected level, direction and size of the herniation, as well as nerve compression, can be achieved in combination with imaging techniques such as X-ray, CT, and MRI. It is important to note that the condition should not be diagnosed based solely on CT or MRI findings without corresponding clinical manifestations.

Differential Diagnosis

Lumbar Muscle Strain

This condition predominantly affects middle-aged individuals and is commonly associated with prolonged maintenance of a single working posture. Chronic pain without an obvious precipitating cause is the main symptom, typically described as a dull, aching discomfort in the lumbar region, which improves with rest. A fixed tender point is often found in the pain area, and tapping this point tends to reduce the pain. The straight-leg raise test is negative, and there are no signs of nerve involvement in the lower limbs. Local anesthetic block at the tender point is highly effective.

Third Lumbar Transverse Process Syndrome

The primary symptom is low back pain, and in some cases, there may be radiating pain along the paraspinal muscles. Examination reveals muscle spasms in the lumbar paraspinal muscles and tenderness over the tip of the transverse process of the L3 vertebra, without signs of neurological involvement. Local anesthetic block provides effective short-term relief.

Piriformis Syndrome

The sciatic nerve may be compressed or irritated as it exits beneath or through the piriformis muscle due to trauma, congenital anomalies, inflammation, hypertrophy, or adhesion of the muscle. Patients primarily complain of pain in the buttocks and lower limbs, with symptom onset and exacerbation often associated with physical activity and significant relief with rest. Physical examination may reveal atrophy of the gluteal muscles, deep tenderness in the buttocks, and a positive straight-leg raise test, although definitive nerve localization signs are usually absent. Symptoms can be induced when the hip is placed in external rotation and abduction against resistance.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

This condition involves narrowing of the spinal canal, nerve root canals, or intervertebral foramina due to various causes, resulting in compression of the spinal cord, cauda equina, or nerve roots in the affected areas. Clinically, the main manifestations include low back pain and symptoms of cauda equina or nerve root compression, with neurogenic claudication as a hallmark feature. Patients often present with numerous subjective complaints but few positive clinical findings. Diagnosis can be confirmed with CT and MRI.

Lumbar Spondylolisthesis and Pars Interarticularis Defects

Patients present with low back pain, and more severe cases may exhibit nerve root symptoms, often accompanied by intervertebral disc degeneration or herniation. Lateral X-rays of the lumbar spine can help determine the degree of spondylolisthesis, while oblique views can reveal pars interarticularis defects. MRI can evaluate spinal cord and nerve compression.

Lumbar Tuberculosis

This condition should be considered in those with a history of tuberculosis exposure or illness, often accompanied by systemic symptoms like low-grade fever in the afternoon and fatigue, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). X-ray imaging may show significant bone destruction, narrowed intervertebral spaces, and cold abscess shadows near the lesion.

Spinal Tumors

Patients experience progressively worsening back pain that does not improve with rest. Malignant tumors may present with anemia, cachexia, elevated ESR, and increased alkaline phosphatase or acid phosphatase levels. Imaging studies such as X-rays, CT, and MRI reveal bone destruction and help differentiate spinal tumors from lumbar disc herniation.

Intraspinal Tumors

Onset tends to be slow and progressive. Initial symptoms often include numbness in the feet, which gradually ascends, with sensory and motor dysfunction and diminished reflexes extending beyond the territory of a single nerve root. Sphincter dysfunction can develop and worsen over time. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis and MRI are crucial for differentiation.

Pelvic Diseases

Early inflammation, tumors, or other pathology in the pelvis can irritate the lumbosacral nerve roots before their primary symptoms fully manifest, resulting in low back or sacral pain, potentially accompanied by radiating pain in the lower limbs. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI can aid in the diagnosis.

Lower Limb Vascular Lesions

Patients presenting with isolated leg pain should be evaluated for vascular pathology. Examination should assess skin temperature, coloration, and vascular pulsations of the lower limbs, and diagnostic tools such as Doppler ultrasonography or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) may be required for confirmation.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Management

Indications

Indications include:

- Patients experiencing their first episode and with a relatively short disease course.

- Symptoms that resolve spontaneously after rest.

- Contraindications to surgery due to systemic or local skin conditions.

- Patients unwilling to undergo surgery.

Treatment Approaches

These include:

- Bed rest for approximately three weeks, followed by gradual mobilization with lumbar support.

- Administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Traction therapy, with pelvic traction being the most commonly employed method.

- Physical therapy modalities.

Surgical Management

Indications

Surgery is indicated in:

- Severe back and leg pain with recurrent episodes that persist or worsen despite more than six months of conservative treatment, significantly affecting work and daily life.

- Central herniation causing cauda equina syndrome or sphincter dysfunction, requiring emergency surgery.

- Clear neurological deficits.

Surgical Techniques

Conventional open surgeries include total laminectomy with nucleus pulposus removal, partial laminectomy with nucleus pulposus removal, and fenestration discectomy.

Microsurgical lumbar discectomy involves the use of a microscope to assist in the removal of the herniated disc.

Minimally invasive disc removal techniques originally started with percutaneous nucleotomy. With advancements in technology, newer methods such as microendoscopic discectomy (MED), percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD), and unilateral biportal endoscopy (UBE)-assisted discectomy have been developed. Among these techniques, PELD has seen rapid growth in clinical use in recent years due to its advantages of minimal tissue damage and quick recovery.

Artificial disc replacement is another surgical option, but its indications remain controversial, and its selection requires careful consideration.