Cervical spondylosis refers to a syndrome caused by the degeneration of the cervical intervertebral discs and its secondary changes, which stimulate or compress adjacent structures such as the spinal cord, nerves, or blood vessels, resulting in a series of symptoms and signs.

Etiology and Pathology

The functional unit of the cervical spine consists of two adjacent vertebrae, the intervertebral disc, the facet joint, and the uncovertebral joint (also known as the Luschka joint or uncinate process). Due to the high degree of mobility in the cervical spine, it is particularly prone to degeneration. The causes of cervical spondylosis include the following:

Degenerative Changes in the Cervical Intervertebral Disc

Degeneration of the intervertebral disc is the most fundamental cause of the development and progression of cervical spondylosis. Disc degeneration leads to narrowing of the intervertebral space, laxity of joint capsules and ligaments, and reduced stability of the spine during movement. This process results in degeneration, hyperplasia, and calcification of structures such as vertebrae, facet joints, uncovertebral joints, anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, and the ligamentum flavum. This creates a vicious cycle of cervical spine instability, eventually leading to symptoms of spinal cord, vascular, or nerve stimulation or compression.

Trauma

Acute trauma can exacerbate preexisting degenerative changes in the cervical spine and intervertebral discs, triggering cervical spondylosis. Chronic trauma can accelerate the degenerative process of the cervical spine, causing symptoms to appear earlier than expected.

Developmental Cervical Spinal Stenosis

During embryonic development and growth after birth, a shortened pedicle can result in a sagittal diameter of the spinal canal smaller than normal. On this foundation, even relatively mild degenerative changes may induce compression symptoms and lead to the onset of disease. The most commonly affected segments, due to their larger range of motion and susceptibility to strain, are C5–C6, followed by C4`–C5· and C6–C7.

Classification and Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of cervical spondylosis are diverse, leading to variability in classification methods. Some classifications remain controversial. A widely used approach includes four basic types:

Radiculopathy Type

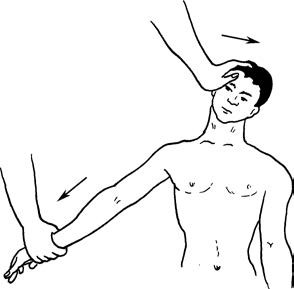

This type has the highest incidence. The condition arises from compression of the corresponding nerve root by herniated intervertebral discs or hypertrophic uncovertebral joints, causing nerve root irritation symptoms. It typically begins with neck and shoulder pain, which worsens over a short period and radiates to the upper limb. The distribution of radiating pain corresponds to the affected dermatome of the compressed nerve root. Skin sensations such as numbness or hypersensitivity and motor dysfunction like weakness in the arm or impaired fine motor control of the fingers may occur. Physical examination may reveal spasms of cervical muscles on the affected side, tenderness in the neck and shoulder area, and restricted mobility of the affected limb. Tests such as the brachial plexus stretch test and Spurling’s test may yield positive results, indicating root pain provocation.

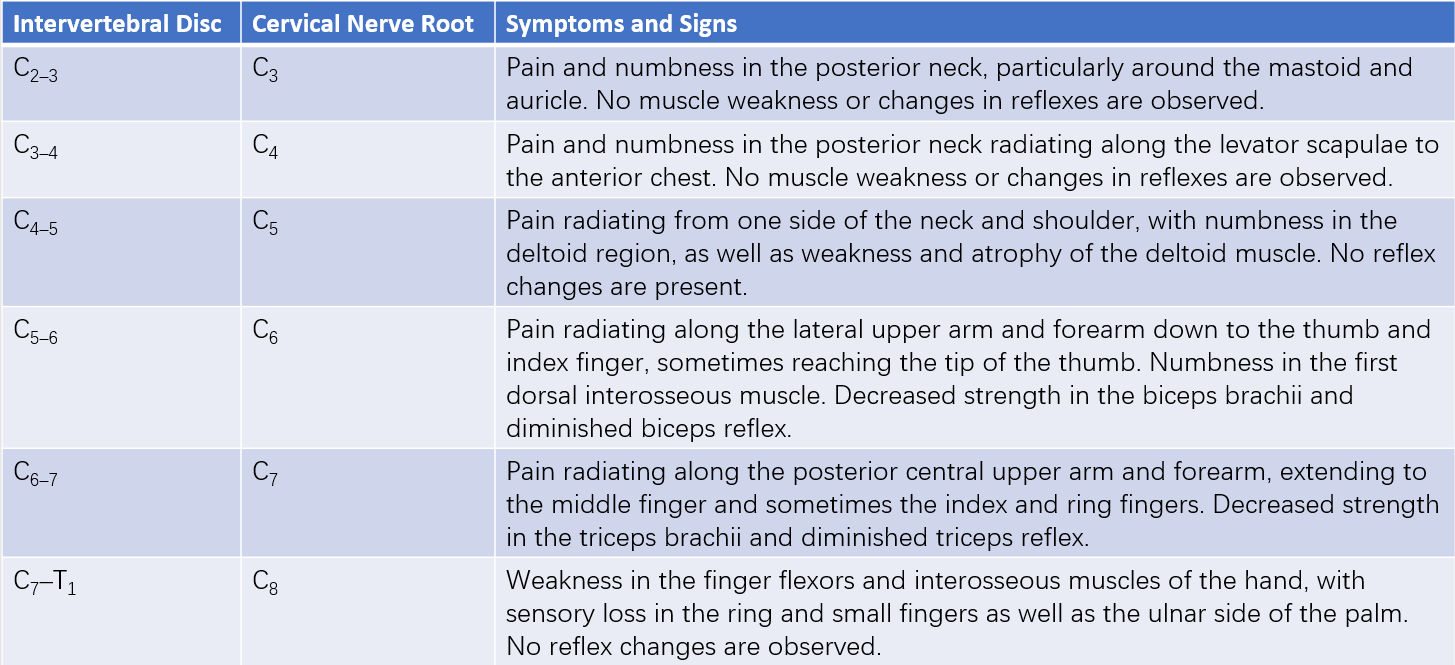

Table 1 Clinical symptoms and signs associated with cervical nerve root involvement

Figure 1 Brachial plexus stretch test (Eaton test)

Figure 2 Compression test (Spurling sign)

Myelopathy Type

This type, which is the most severe form of cervical spondylosis, results from compression of the spinal cord or its blood supply by degenerative cervical spine structures. Symptoms include a syndrome of sensory, motor, reflex, and sphincter dysfunction in all four limbs. The lower cervical spine (where the spinal cord enlarges) is particularly vulnerable due to its smaller canal size and greater mobility, leading to early and significant degenerative changes as well as vulnerability to spinal cord compression. Patients may experience numbness, weakness, or stiffness in the upper or lower limbs, a sensation of walking on cotton wool, a band-like sensation across the torso, and difficulty with fine motor tasks involving the hands. In advanced stages, bladder and bowel dysfunction may occur. Physical examination may reveal sensory deficits, decreased muscle strength, hyperactive or heightened deep tendon reflexes in all four limbs, and weakened or absent superficial reflexes. Pathological reflexes such as Hoffmann’s sign and Babinski’s sign may be positive.

Vertebral Artery Type

It is currently thought that this type involves mechanical compression or irritation of the vertebral artery due to cervical spine degeneration or segmental instability. This results in vertebral artery stenosis, tortuosity, or spasm, leading to insufficient blood supply to the vertebrobasilar circulation. Symptoms include dizziness, nausea, tinnitus, and migraines, or sudden vertigo and collapse when the neck moves. However, some argue that bony spurs or disc herniation rarely cause complete vertebral artery compression severe enough to induce vertigo or collapse, making this subtype somewhat controversial.

Sympathetic Type

This type is believed to result from degenerative changes such as disc herniation or facet joint hypertrophy, particularly cervical spinal instability, stimulating or compressing sympathetic nerve fibers in the neck. It is closely associated with activities that involve prolonged forward head posture or desk work. Symptoms related to either sympathetic excitation or inhibition can occur. These may include neck pain, headaches, dizziness, palpitations, and arrhythmias. Some patients may report memory impairment or insomnia. This type generally presents with numerous symptoms but few clinical signs, and its classification remains controversial in clinical practice.

Imaging Examinations

The diagnosis of cervical spondylosis requires a combination of imaging findings, clinical symptoms, and electromyography-related examinations. Imaging findings alone are insufficient as the sole basis for diagnosis.

X-ray Imaging

X-ray imaging is primarily used to exclude other pathologies. It can reveal changes in cervical curvature, such as reduced or lost physiological lordosis or kyphotic curves, as well as osteophyte formation along the anterior and posterior vertebral margins and intervertebral space narrowing. Oblique views may show narrowing of the intervertebral foramina. Dynamic studies involving flexion and extension views can demonstrate segmental cervical instability.

CT (Computed Tomography) Scanning

CT scans can show intervertebral disc herniation, a reduced sagittal diameter of the cervical spinal canal, ossification of the ligamentum flavum, loss of epidural fat, and evidence of spinal cord compression.

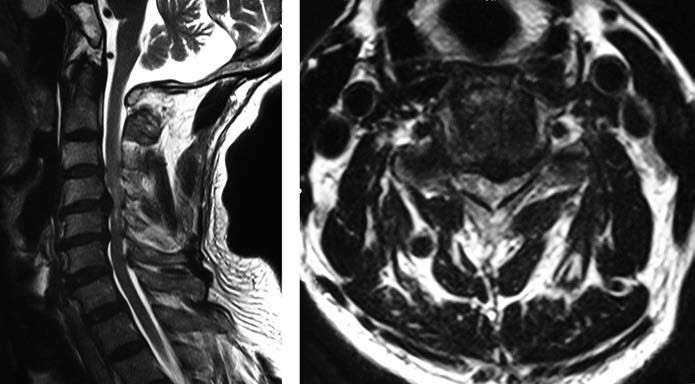

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

MRI findings on T1-weighted images include intervertebral disc herniation, while T2-weighted images may reveal the disappearance of the epidural space, low signal intensity of the intervertebral disc, spinal cord compression, or high signal areas within the spinal cord.

Figure 3 MRI findings of myelopathy-type cervical spondylosis

Diagnosis

In middle-aged and older patients, a diagnosis can generally be established based on the medical history, physical examination (particularly neurological examination), and imaging studies such as X-rays, CT, or MRI. The radiculopathy type of cervical spondylosis is common and typically presents with characteristic symptoms, making diagnosis relatively straightforward. However, the clinical presentation of other types is complex, highlighting the importance of differential diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Radiculopathy Type

Degenerative changes in the cervical spine can compress one or multiple nerve roots, resulting in symptoms resembling peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes such as thoracic outlet syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome, and Guyon’s canal syndrome. These syndromes typically involve bony and fibrous factors causing local nerve entrapment and can be distinguished through careful physical examination, imaging studies, and electromyography (EMG). Additionally, differentiation from frozen shoulder is necessary. Frozen shoulder frequently occurs around the age of 50 and primarily presents with shoulder pain localized above the elbow, without numbness or muscle weakness.

Myelopathy Type

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) often occurs in patients around 40 years old, with abrupt onset and rapid disease progression. It primarily presents with limb motor dysfunction and typically involves muscle weakness without sensory deficits. Muscle atrophy is most apparent in the intrinsic hand muscles and progresses proximally to involve the shoulders and neck. Shoulder muscle atrophy is rare in cervical spondylosis, and examination of the sternocleidomastoid and tongue muscles may be informative. EMG may show spontaneous potentials in the sternocleidomastoid and tongue muscles.

Syringomyelia mainly affects young and middle-aged individuals and often presents with dissociated sensory loss. Pain and temperature sensations are lost, while touch and proprioception are preserved. Due to neurogenic joint instability and a lack of pain perception, Charcot joints (neurogenic arthropathy) may develop. MRI findings show abnormal cyst-like signals within the spinal cord consistent with cerebrospinal fluid.

Vertebral Artery Type

This subtype has a complex presentation, making differential diagnosis more challenging. Distinguishing it from vestibular diseases, cerebrovascular disorders, and extraocular muscle disorders is essential. It is necessary to rule out Ménière’s disease.

Sympathetic Type

This type often presents with complex clinical features, including symptoms resembling neurosis, and lacks clear objective diagnostic criteria. Cardiovascular conditions should be excluded, and other conditions causing dizziness—such as those of cerebral, auditory, visual, traumatic, or psychogenic origin—should be distinguished.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Treatment

Non-surgical approaches may include cervical traction, cervical immobilization, physical therapy, correction of poor working posture and sleeping positions, and adjustment of pillow height. These methods are often supplemented with medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, and neurotrophic agents.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Indications

Surgery may be indicated in cases of severe radicular pain unresponsive to conservative treatment, significant spinal cord or nerve root compression with neurological dysfunction, or when symptoms are not severe but conservative treatment fails for six months, impacting daily life and work.

Common Surgical Procedures for Cervical Spondylosis

Anterior Cervical Decompression and Fusion (ACDF)

The most commonly used approach involves procedures such as anterior cervical discectomy, subtotal vertebrectomy, neural decompression, and interbody fusion with bone grafting.

Posterior Decompression Surgery

This approach involves spinal cord posterior shift for "indirect decompression." Conventional methods such as partial or total laminectomy are less commonly used today. More common procedures now include laminoplasty (single- or double-door technique) for spinal canal enlargement, preserving cervical spine mobility. Additionally, posterior decompression combined with lateral mass or pedicle screw fixation and fusion is employed.