This condition, also referred to as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease or flattened hip, describes ischemic necrosis of the femoral head epiphysis. Among childhood osteochondrosis conditions, it has a relatively high prevalence and significant potential for disability. Ischemic necrosis of the femoral head in adults caused by various factors is not included in this category.

Etiology

The cause is unknown, with approximately 10% of cases being familial. Chronic injury represents an important contributing factor. Trauma can lead to occlusion of epiphyseal blood vessels, resulting in secondary ischemic necrosis. The blood supply to the femoral head epiphysis undergoes significant changes from birth to 12 years of age. Between the ages of 4–9, the epiphysis is supplied by a single external epiphyseal artery, rendering the blood supply poorest during this period. Even minor trauma during this time can disrupt blood flow. After the age of 9, vessels of the ligamentum teres contribute to the blood supply of the femoral head epiphysis, leading to a decline in incidence. Following the ossification and fusion of the epiphyseal plate, the metaphyseal blood vessels penetrate the femoral head, eliminating the risk of this condition.

Pathology

Ischemic changes in the femoral head epiphysis typically follow four pathological stages.

Ischemic Phase

Subchondral bone cells undergo necrosis due to ischemia, and the ossification center ceases growth. However, the epiphyseal cartilage can continue to develop by absorbing nutrients from synovial fluid, potentially becoming thicker than normal due to stimulation.

Revascularization Phase

New blood vessels grow into the necrotic epiphysis from surrounding tissues, gradually forming new bone. If persistent external trauma continues to affect the area, the newly formed bone may be resorbed and replaced by fibrous granulation tissue, increasing susceptibility to deformation of the femoral head.

Healing Phase

At this stage, bone resorption ceases after a certain period, and ossification continues until the fibrous granulation tissue is fully replaced by new bone. During this process, malformations may worsen, and damage to the articular cartilage of the acetabulum can also occur.

Residual Deformity Phase

The pathological changes stabilize, and deformities become fixed. Over time, as the individual ages, the deformities may eventually progress to osteoarthritis of the hip joint.

Clinical Manifestations

This condition is most commonly observed in children aged 3–10, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 6:1. Unilateral involvement is more frequent, but 10%–20% of cases present bilaterally.

Hip pain gradually worsens, often involving referred pain to the inner upper knee of the affected limb in some patients. This presentation necessitates examination of the ipsilateral hip joint. Progressive pain leads to limping and a waddling gait, with severity correlating to the restriction of hip mobility.

The Thomas test is positive, with affected limb findings including muscle atrophy, adductor muscle spasms, and marked limitations in internal rotation, abduction, and extension of the hip. In later stages, the affected limb is slightly shorter than the healthy side.

X-ray Imaging

In the early stages, radiographs may reveal a reduced and denser epiphysis, widening of the medial joint space, irregularities in the growth plate, and metaphyseal radiolucency. A crescent sign indicative of subchondral fracture may appear.

As the condition progresses, density increases in the femoral head, accompanied by epiphyseal fragmentation, flattening, thickening of the femoral neck, and evidence of partial hip dislocation. X-ray findings closely align with the pathological evolution.

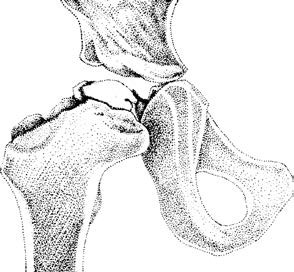

Figure 1 Early-stage osteochondrosis of the femoral head (left side). The ossification center appears smaller and denser compared to the healthy side, with widening of the joint space.

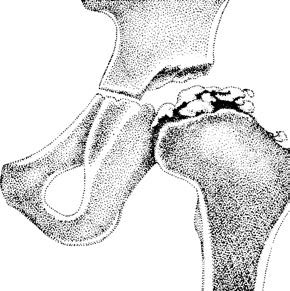

Figure 2 Revascularization phase. The ossification center is small and dense, surrounded by new bone deposition, with deformation of both the femoral head and neck.

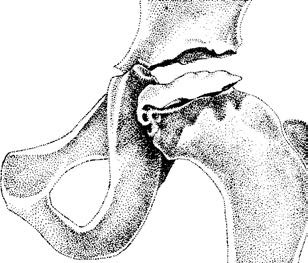

Figure 3 Advanced revascularization phase. Fragmentation of the ossification center is evident, with femoral head flattening and femoral neck thickening.

Figure 4 Healing phase. The epiphysis is flat and slightly denser, with no fragmentation, and the femoral neck remains thickened.

Radionuclide Bone Scintigraphy

During the ischemic phase, X-rays may appear negative. However, scintigraphy can display reduced radionuclide uptake and decreased femoral head perfusion. Quantitative analysis of the affected-to-healthy side ratio shows values below 0.6 as abnormal, with an early diagnostic accuracy exceeding 90%.

Treatment

The goal is to preserve an optimal anatomical and biomechanical environment to prevent femoral head deformation during the revascularization and healing phases. Treatment principles include: (1) full containment of the femoral head within the acetabulum; (2) avoidance of localized compressive stress from the superolateral edge of the acetabulum; (3) reduction of pressure on the femoral head; and (4) maintenance of good hip joint range of motion.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Fixing the affected hip in 40° abduction with slight internal rotation using a brace is recommended. During the day, mobilization with crutches is advised while wearing the brace, whereas at night the brace may be replaced with a triangular pillow to maintain the same position. The brace is typically worn for 1–2 years, with regular X-ray monitoring of disease progression until complete femoral head reconstruction is achieved.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical options include synovectomy, varus/rotational intertrochanteric osteotomy, pelvic osteotomy, and vascularized bone grafting. These procedures can alleviate symptoms but rarely fully restore femoral head morphology. Early diagnosis and intervention are critical to minimizing disability.