The tibial tubercle serves as the attachment point for the patellar ligament. Around the age of 16, the epiphysis of the tibial tubercle fuses with the epiphysis of the proximal tibia, and by the age of 18, the tibial tubercle fully integrates with the proximal tibia. Before the age of 18, this area is vulnerable to injury, leading to epiphysitis or even ischemic necrosis. Osteochondrosis of the tibial tubercle, also known as Osgood-Schlatter disease, refers to this condition.

Etiology

The quadriceps femoris is one of the strongest muscle groups in the body. The traction force generated by this muscle, transmitted through the patella and patellar ligament, can cause various degrees of tearing in the unossified epiphysis of the tibial tubercle.

Clinical Manifestations

This condition commonly occurs in active children aged 9–14 years, with girls typically presenting earlier than boys by 1–2 years. Among adolescents who participate actively in sports, the incidence is approximately 20%, with 25%–50% of cases involving both sides. There is often a history of recent intense physical activity. The clinical presentation is characterized by gradually developing pain and swelling at the tibial tubercle, with pain being strongly correlated with physical activity.

Examination reveals pronounced swelling at the tibial tubercle without signs of skin inflammation. The area is firm to the touch and exhibits significant tenderness. Pain intensifies during knee extension with resistance, quadriceps stretching, or full knee flexion during squatting.

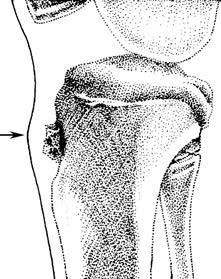

Figure 1 Osteochondrosis of the tibial tubercle

Epiphyseal tearing, increased bone density, and swelling of the soft tissue.

Patients with typical clinical features do not require X-ray imaging. For atypical cases, X-rays may show findings such as enlargement, increased density, or fragmentation of the tibial tubercle epiphysis, along with swelling of the surrounding soft tissue.

Treatment

Osteochondrosis of the tibial tubercle is generally a benign, self-limiting condition. Most patients respond well to conservative management. Symptoms typically resolve spontaneously after the tibial tubercle ossifies and integrates with the proximal tibia by the age of 18, although the localized swelling remains unchanged. For individuals with significant pain, ice application, short-term use of analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the use of tibial tubercle pads may be beneficial. Once pain is adequately controlled, rehabilitation exercises and physical therapy are advised. Complete avoidance of physical activity is unnecessary for this condition.

Corticosteroid injections in this area are not recommended. Subcutaneous injections have proven ineffective, and epiphyseal injections are technically challenging. There have been reports of severe complications, such as skin necrosis and prolonged exposure of the epiphyseal bone, following subcutaneous corticosteroid injections.

In rare cases, adults may experience persistent symptoms if small epiphyseal fragments fail to fuse with the tibial tubercle. These cases may require surgical interventions such as drilling or bone grafting. Surgical treatment is generally reserved for cases unresponsive to conservative management and is typically performed after closure of the proximal tibial growth plate. Procedures such as partial bone resection or tibial tubercle excision have been shown to alleviate symptoms.