The supraspinous ligament originates from the external occipital protuberance and terminates at the spinous process of the fifth lumbar vertebra. It attaches to the surface of the spinous processes. In the cervical spine, the supraspinous ligament is broad and thick and is referred to as the nuchal ligament. In the thoracic region, it becomes thinner, while in the lumbar region, it is relatively wider again. Therefore, trauma to the supraspinous ligament is more common in the mid-thoracic region. The interspinous ligament, which connects the spinous processes of adjacent vertebrae, consists of tendinous tissue arranged in three layers of fibers that are interwoven, making it prone to chronic injuries. The primary function of these ligaments is to prevent damage resulting from excessive forward flexion of the spine. Since there is no supraspinous ligament at the L5–S1 level and this area experiences the highest stress as a junction between the mobile lumbar spine and the fixed sacral spine, interspinous ligament injuries are most likely to occur at this site.

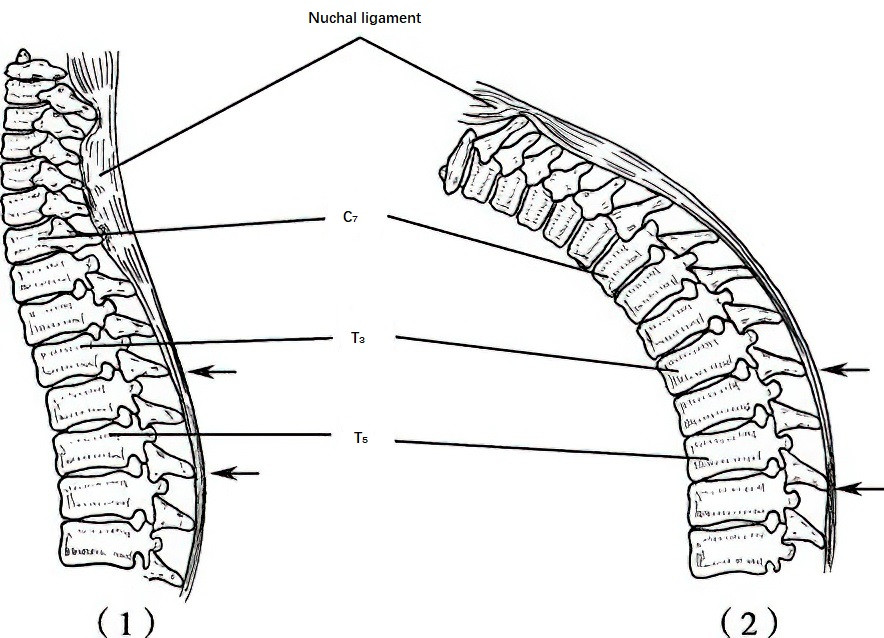

Figure 1 Supraspinous ligament injury

(1) Schematic of the supraspinous ligament in the neutral position of the cervicothoracic spine

(2) Forward-flexed working posture:

Superior arrow: Region of initial ligament thinning

Inferior arrow: Zone of significant ligament attenuation

Both areas are subjected to significant tensile forces.

Etiology and Pathology

Individuals who work for prolonged periods while bent forward without changing positions are at higher risk. Spinal instability due to injury or illness causes the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments to remain under continuous tension, resulting in small tears, hemorrhage, and exudation. Degenerative changes increase the susceptibility to injury. This type of inflammatory irritation can affect branches of the posterior rami of the lumbar nerves innervating the ligaments, leading to low back pain. In chronic cases, ligament calcification may occur. Degenerative or ruptured areas where the supraspinous ligament connects to the spinous process may detach from the spinous process. Additionally, traumatic ruptures of the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, if complicated by immobilization issues or poor stabilization following injury, can lead to significant scar tissue formation, contributing to chronic low back pain.

Clinical Manifestations

Most patients lack a history of overt trauma. Chronic low back pain persists, and during hyperextension movements, compression of the affected interspinous ligaments can provoke pain. In some cases, pain may radiate to the sacral or gluteal regions but does not extend beyond the knee joint. During physical examination, tenderness is often noted at the spinous process or the interspinous space corresponding to the injured ligament, though there is typically no redness or swelling. Occasionally, the supraspinous ligament may be palpated sliding over the spinous process. Ultrasonography or MRI can confirm interspinous ligament injuries.

Treatment

The vast majority of cases are managed with non-surgical treatment. Recovery may be slow if the causative factors leading to strain are not addressed.

After the onset of symptoms, avoiding forward bending as much as possible helps create a favorable environment for ligament repair.

Local corticosteroid injections can significantly relieve symptoms. Immobilization with a lumbar brace during treatment may help reduce the duration required for recovery.

Physiotherapy has a certain degree of therapeutic efficacy. Manipulation or massage has limited benefits for this condition, serving mainly to reduce secondary spasms of the sacrospinalis muscles.

For cases with prolonged symptoms and failure of non-surgical treatment, fascial strip repair procedures may be performed, although their effectiveness remains uncertain.