Low back and leg pain refers to discomfort occurring in the lower back, lumbosacral, sacroiliac, or buttock regions, which may be accompanied by pain in one or both lower limbs and symptoms of cauda equina nerve compression. The clinical manifestations are diverse, the course of the condition is often prolonged, and treatment can be challenging. Understanding the etiology and emphasizing prevention hold significant clinical value. Low back and leg pain is merely a set of clinical symptoms, and identifying the underlying cause is critical for effective treatment. Psychological factors in patients should also be considered during diagnosis and management.

Anatomical and Physiological Considerations

The lumbar segment of the spine exhibits a physiological lordosis, whereas the sacral segment presents a kyphosis. The spine functions as the body's support structure and forms an S-shape in the sagittal plane. During upright activities, various loads and stresses concentrate on the lumbosacral region, making it prone to acute and chronic injury as well as degenerative changes.

The vertebrae are connected by intervertebral discs, facet joints, anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, ligamentum flavum, supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, and intertransverse ligaments. Stabilization is further supported by muscles such as the sacrospinalis, lumbar, and abdominal muscles. Damage to any of these structures may disrupt the spine's stability and balance, causing symptoms.

Intervertebral discs consist of the cartilage endplates (top and bottom), a central nucleus pulposus, and a surrounding annulus fibrosus. The cartilage endplates and nucleus pulposus lack blood supply and nerve structures, making self-repair difficult following disc injury.

The loading on the lumbar intervertebral discs varies with posture. Taking spinal load in the standing position as 100%, it increases to 150% in the seated position, 210% while standing and bending forward, and 270% in the seated, forward-bending position. Using a lumbar support device can reduce the load by approximately 30%. This highlights that forward-flexion postures and weight-bearing contribute to lumbar spine degeneration and injury. Occupations involving such postures (e.g., driving or foundry work) are associated with higher incidences of low back and leg pain.

Lumbar spinal stenosis or degenerative and proliferative changes in the small joints can narrow the nerve root canals and intervertebral foramina, compressing or irritating the cauda equina and lumbar nerve roots, resulting in related symptoms and signs.

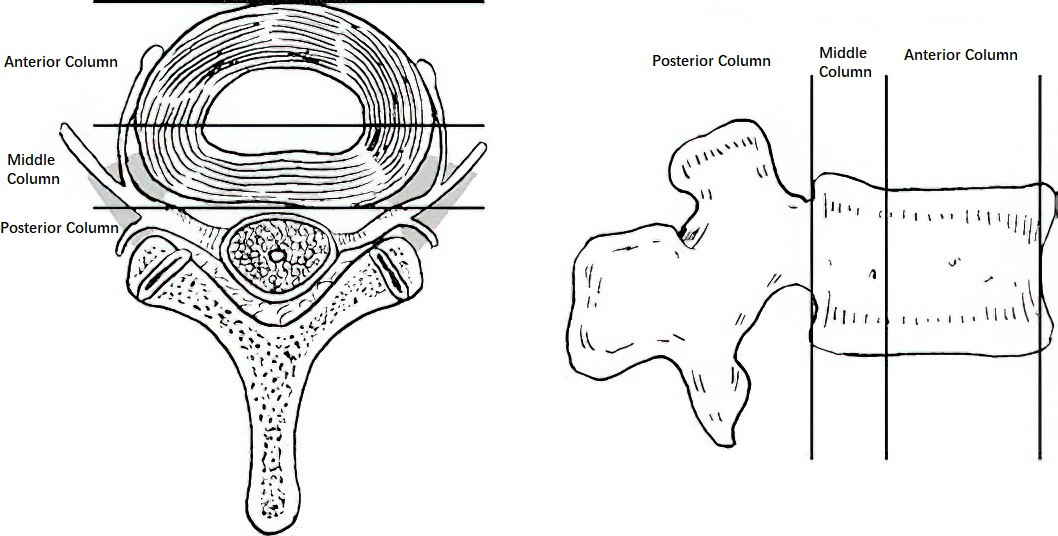

Overuse injuries are closely related to the biomechanics of the vertebral column. Dennis and Ferguson proposed the "three-column theory" of the spine, suggesting that spinal stability depends on the integrity of the middle column rather than solely on the posterior ligament complex. The spine is divided into three columns:

- Anterior column: Includes the anterior longitudinal ligament and the anterior two-thirds of the vertebrae and intervertebral discs.

- Middle column: Includes the posterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior one-third of the vertebrae and intervertebral discs.

- Posterior column: Includes the vertebral arches, ligamentum flavum, and interspinous ligaments.

The anterior column bears compressive forces, while the posterior column bears tensile forces. Chronic injuries to lumbar muscles (e.g., fasciae, ligaments, or periosteum at attachment points) often result from the significant stress endured by the low-positioned lumbar region during movement. The three-column theory provides a useful framework for understanding spinal biomechanics.

Figure 1 Spinal three-column regions

Etiology and Classification

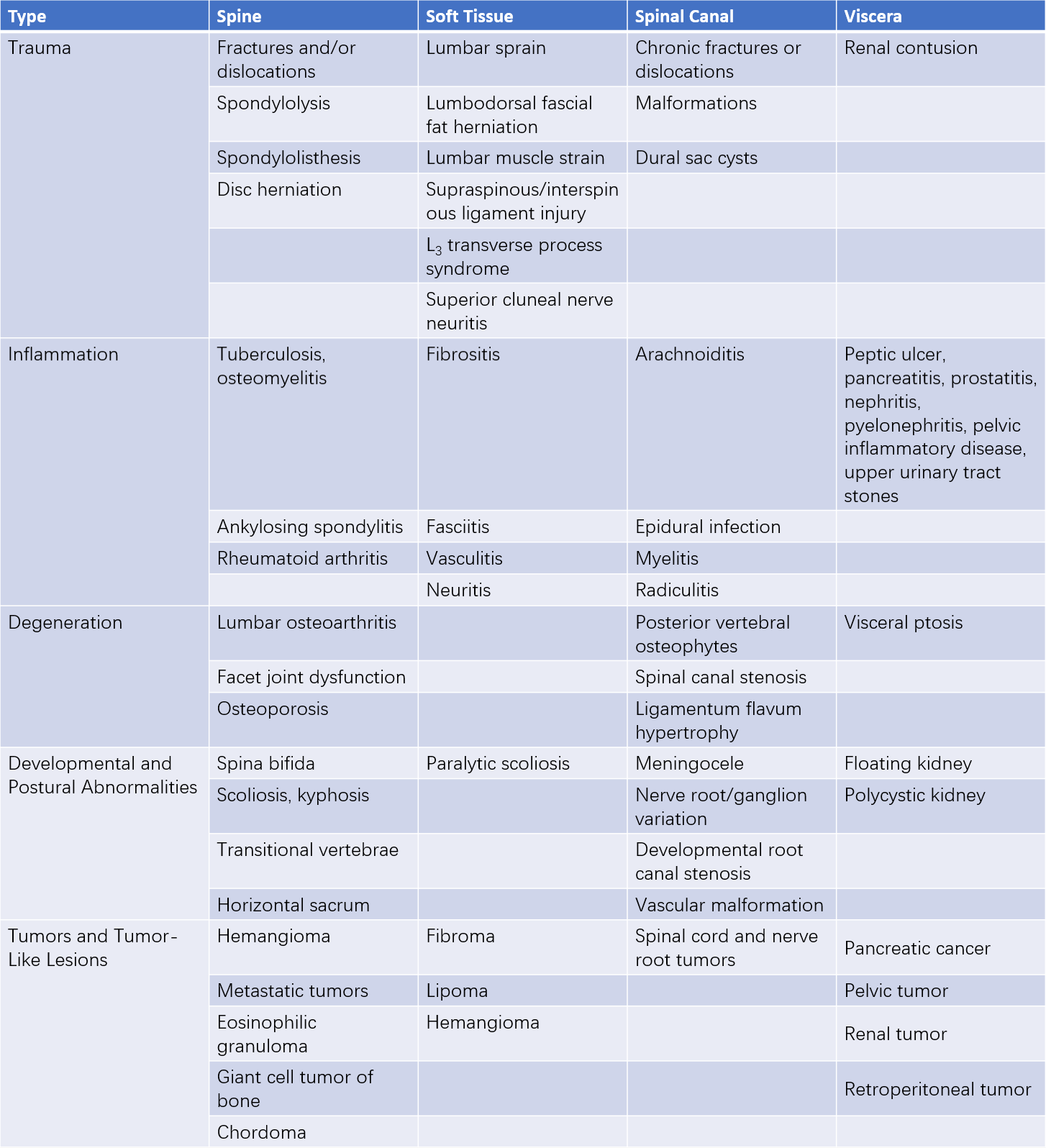

No universally accepted or comprehensive classification system currently exists for the causes of low back and leg pain. Table 1 lists common causes.

Table 1 Classification of etiologies for low back and leg pain

Pain Characteristics and Tender Points

Characteristics of Pain

Localized Pain

This is caused by the primary lesion or secondary muscle spasms. The pain is usually well-defined and localized, with a fixed and marked tender point. Anesthetic-based local blocking can relieve the pain rapidly in a short period.

Referred or Reflective Pain

Often termed as reflex pain, this arises from irritation due to conditions of the lumbosacral spine or abdominal and pelvic organs, which are transmitted to the posterior spinal roots or spinothalamic tract and corresponding first- or second-order neurons. This results in excitation of neurons at the same spinal segment, leading to abnormal sensations in the corresponding skin distribution. The pain is poorly localized, lacks clear objective signs of nerve damage, but may appear with muscle spasms.

Radicular Pain

This is a hallmark of nerve root damage. The pain radiates along the affected nerve to the periphery and is typically accompanied by characteristic sensory, motor, and reflex impairments that help in localization.

Tender Points

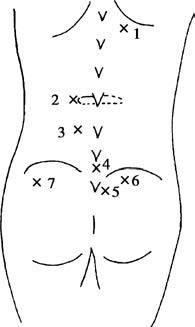

Identifying tender points is easier when the patient is in the prone position with relaxed muscles. Superficial tissue diseases often present with specific tender locations. For example:

Tender points for supraspinous or interspinous ligament strain are located on the surface of the spinous processes or between adjoining spinous processes.

- Tender points for the L3 transverse process syndrome are found at the tips of the transverse processes.

- Tender points for gluteal fasciitis are often located below the inner iliac crest.

- Tender points for superior cluneal nerve neuritis are located over the outer one-third of the iliac crest.

- Tender points for lumbar strain are located at the outer-medial edge of the lumbosacral paraspinal muscles.

- Tender points for sacroiliac ligament strain are found between the lumbosacral vertebrae and the posterior superior iliac spine.

Figure 2 Common tender points in low back pain

1, Costovertebral angle

2, Tip of the L3 transverse process

3, Sacrospinalis muscle

4, L5–S1 interspinous space

5, Upper sacroiliac joint

6, Iliac crest origin of gluteal muscles

7, Superior cluneal nerve

Deeper structural disorders (e.g., involving facet joints, vertebral bodies, or intervertebral discs) tend to exhibit deep pressure tenderness or percussion pain over the affected structure, which is harder to identify clearly compared to soft tissue conditions.

Treatment

Non-Surgical Treatment

The vast majority of patients with low back and leg pain achieve relief or resolution through non-surgical methods.

- Rest in bed, minimize forward-bending activities, and use lumbar support devices to reduce stress and avoid further injury.

- Regular lumbar and back muscle strengthening exercises can enhance lumbar stability and delay spinal degeneration.

- Traction, physical therapy, manipulation, and massage can relax spasmodic paraspinal muscles, reduce intervertebral disc pressure, and alleviate inflammation-induced nerve root irritation. Violent or forceful massages are contraindicated.

- Appropriate use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may help relieve symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is considered for patients with clearly identified causes of low back and leg pain (e.g., lumbar disc herniation or lumbar spinal stenosis) that fail to respond to rigorous non-surgical treatment.