Applied Anatomy

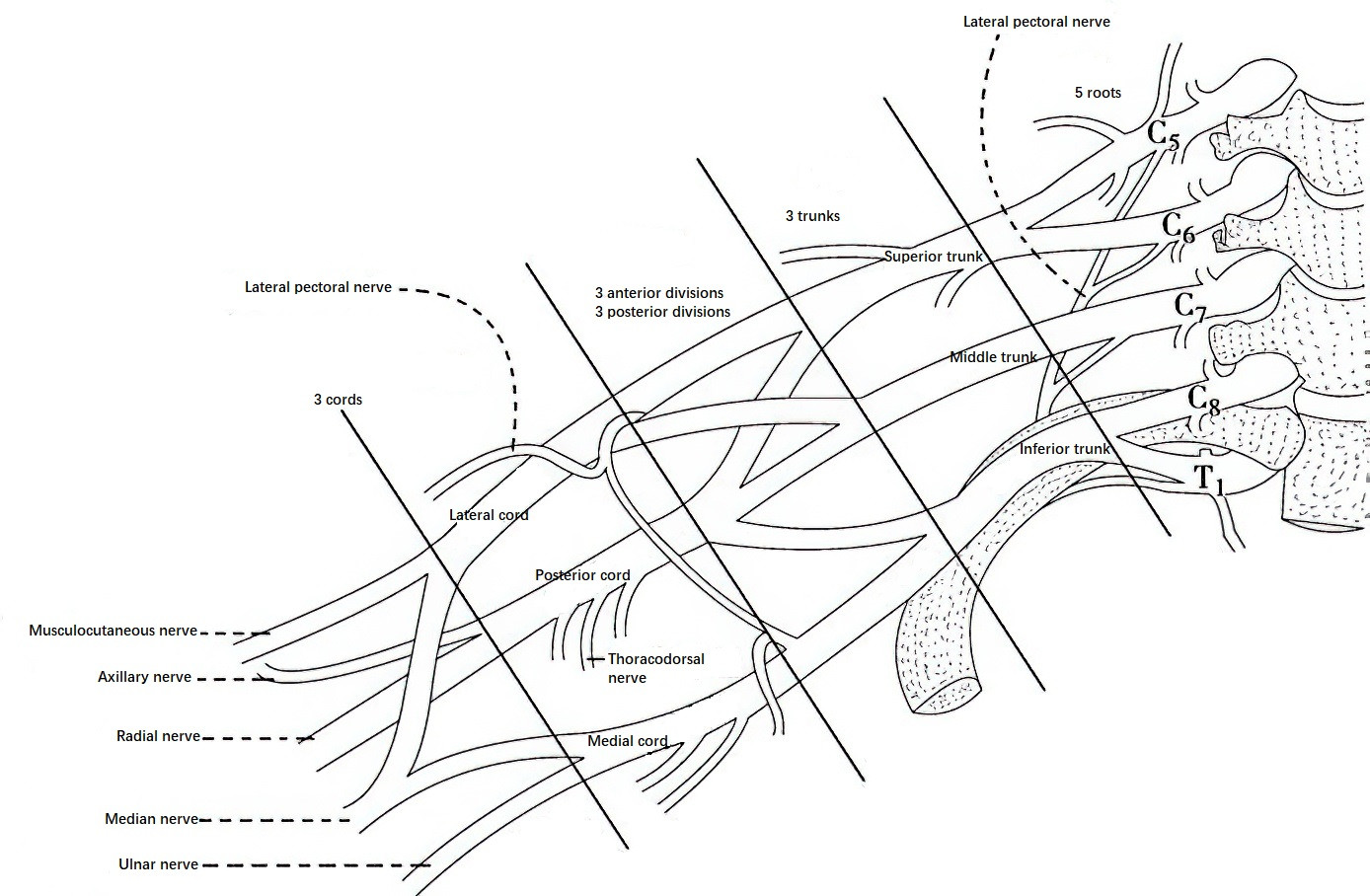

The nerves of the upper limb originate from the brachial plexus, which is formed by the anterior rami of C5–C8 cervical nerve roots and the T1 thoracic nerve root. At the lateral border of the anterior scalene muscle, the C5 and C6 roots form the upper trunk, the C7 root continues as the middle trunk, and the C8 and T1 roots form the lower trunk. These trunks extend outward and downward, and at the middle level of the clavicle, each trunk divides into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks form the lateral cord, the anterior division of the lower trunk becomes the medial cord, and the posterior divisions of all three trunks join to form the posterior cord.

Figure 1 Brachial plexus composition

At the level of the coracoid process, the cords give rise to nerve branches. The lateral cord gives rise to the musculocutaneous nerve and the lateral head of the median nerve. The medial cord gives rise to the ulnar nerve and the medial head of the median nerve. The posterior cord gives rise to the axillary nerve and the radial nerve. The two heads of the median nerve eventually converge anterior to the axillary artery, forming the median nerve proper.

Brachial Plexus Injury

Brachial plexus injuries, often caused by traction, are frequently encountered in automobile or motorcycle accidents, falls from heights, heavy object compression of the shoulder and neck, machinery-induced injuries, and difficult childbirth. When the head and shoulder are forcibly pulled apart in opposite directions, an injury to the upper trunk of the plexus may occur, and in severe cases, the middle trunk may also be affected. Injuries to the lower trunk are often caused by the affected limb being pulled upward and toward the head, as in cases where the arm is caught in belts or conveyor systems. Excessively forceful traction can result in complete brachial plexus injuries or even avulsion of nerve roots from their origin in the spinal cord.

Brachial plexus injuries may present as upper plexus, lower plexus, or complete plexus injuries.

Injuries to the C5 and C6 roots or the upper trunk cause paralysis of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, deltoid, teres minor, and biceps brachii, resulting in dysfunction of shoulder abduction and elbow flexion.

Injuries to the C8 and T1 roots or the lower trunk lead to paralysis of the muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve, as well as partial dysfunction of the muscles innervated by the median and radial nerves.

Isolated injuries to the C7 root or the middle trunk are rare and are usually associated with upper or lower trunk injuries, often manifesting as radial nerve dysfunction.

Complete brachial plexus injuries result in flaccid paralysis of all muscles of the upper limb.

Brachial plexus injuries caused by root avulsion may present with Horner’s syndrome, characterized by ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis on the affected side.

Sensory deficits or loss occur in the corresponding dermatomes of the affected nerve roots. The dermatomal distribution is as follows: C5 – lateral aspect of the upper arm; C6 – lateral forearm and thumb/index finger; C7 – middle finger; C8 – ring and little fingers and medial forearm; T1 – medial aspect of the upper arm (mid-lower segments).

Treatment for brachial plexus injuries depends on the type, location, and severity of the injury. Root avulsion injuries may require early exploration and nerve transfer. Open injuries, injuries caused by medication, or iatrogenic injuries often warrant early surgical repair. Closed traction injuries may be observed for three months. If no significant recovery is noted, surgical exploration is recommended, which may include neurolysis, neurorrhaphy, or nerve grafting. In late-stage brachial plexus injuries or cases with no functional recovery after nerve repair, residual functional muscles may be repurposed through muscle or tendon transfer, or joint fusion may be considered to restore some essential functions.

Injury of the Median Nerve

The median nerve is formed by the lateral and medial heads of the median nerve from the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus. Near the origin of the coracobrachialis muscle, it proceeds anterior to the axillary artery and then runs medially alongside the brachial artery. At the elbow, it passes beneath the bicipital aponeurosis and enters the forearm, traveling between the humeral and ulnar heads of the pronator teres. It then descends between the flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus. At the distal forearm, it emerges between the tendons of the flexor carpi radialis and palmaris longus and enters the palm through the carpal tunnel.

In the arm, the median nerve gives off no branches. In the forearm, it innervates the pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum profundus (index and middle fingers), flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus. In the palm, it innervates the abductor pollicis brevis, lateral head of the flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and the first and second lumbricals. The three common palmar digital nerves of the median nerve provide sensory innervation to the palmar surface and proximal dorsal surface beyond the proximal interphalangeal joints of the radial 3½ fingers (thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring finger).

Median nerve injuries are often caused by supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children or by lacerations near the wrist. Injuries at the wrist result in paralysis of the thenar and lumbrical muscles, leading to an inability to oppose the thumb and sensory deficits over the radial 3½ fingers, particularly with loss of sensation in the distal phalanges of the index and middle fingers. Injuries above the elbow result in additional paralysis of the forearm muscles, causing loss of thumb, index, and middle finger flexion, in addition to the wrist-level deficits described above.

Closed compression injuries to the median nerve warrant short-term observation. If no signs of recovery are noted, surgical exploration is often necessary. Open injuries should be repaired as early as possible, either through primary repair or delayed repair. In cases where functional recovery is absent following nerve repair, tendon transfer can be utilized to reconstruct thumb opposition.

Injury of the Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve is a continuation of the medial cord of the brachial plexus. It descends along the medial side of the brachial artery and gradually moves to the posterior side at the mid-arm level. It passes through the ulnar groove on the posterior side of the medial epicondyle of the humerus and travels between the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. From there, it enters the palmar side of the forearm, running between the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus, and follows the ulnar artery in the forearm. Branches from the ulnar nerve supply the flexor carpi ulnaris and the flexor digitorum profundus for the ring and little fingers. At approximately 5 cm proximal to the wrist, it gives off the dorsal branch, which provides sensation to the ulnar side of the dorsal hand skin. Passing through the ulnar canal (Guyon’s canal) between the pisiform and hamate bones, the ulnar nerve divides into deep and superficial branches. The deep branch penetrates the hypothenar muscles to reach the deep palm, innervating the hypothenar muscles, all interossei, the third and fourth lumbricals, the adductor pollicis, and the medial head of the flexor pollicis brevis. The superficial branch provides sensory innervation to the palmar side of the ulnar half of the hand and the ulnar one and a half fingers.

The ulnar nerve is prone to injury at both the wrist and the elbow. Wrist-level injuries typically result in paralysis of the interossei, the third and fourth lumbricals, and the adductor pollicis, leading to clawing deformity of the ring and little fingers, difficulties with finger adduction and abduction, and the presence of Froment’s sign. Sensory deficits may affect the ulnar side of the hand and the ulnar one and a half fingers, especially with sensory loss in the little finger. Injuries above the elbow may additionally cause impaired flexion at the distal joints of the ring and little fingers, typically presenting as weakened, rather than completely absent, flexion.

Recovery of intrinsic hand muscle function following ulnar nerve repair is often poor, especially in high-level injuries. Early exploration and microsurgical repair are crucial. For late-stage injuries or cases with persistent claw deformity despite nerve repair, functional reconstruction techniques may be employed to correct the deformity.

Injury of the Radial Nerve

The radial nerve arises from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It travels posteriorly to the axillary artery and runs across the subscapularis and teres major muscles in a downward and backward direction. The nerve then traverses the radial groove of the humerus, descending laterally along the lateral head of the triceps brachii. At the elbow, it passes between the brachialis and brachioradialis muscles and enters the forearm between the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus, at which point it divides into superficial and deep branches. The superficial branch accompanies the radial artery, traveling deep to the brachioradialis and turning dorsally approximately 5 cm above the radial styloid process to innervate the skin on the radial side of the dorsum of the hand and the radial three and a half fingers. The deep branch, also known as the posterior interosseous nerve, winds around the neck of the radius and pierces the supinator muscle to reach the dorsal side of the forearm.

The radial nerve provides motor innervation to the triceps brachii at the arm level. At the elbow, it supplies the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus. Its deep branch innervates the extensor carpi radialis brevis, supinator, extensor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, extensor indicis, extensor digiti minimi, abductor pollicis longus, and the extensor pollicis longus and brevis.

The radial nerve is particularly vulnerable at the mid-to-distal third junction of the humerus, where it lies in close proximity to the bone. Fractures at this site often cause radial nerve injury, leading to impaired wrist, thumb, and finger extension, as well as difficulties with forearm supination. Sensory abnormalities frequently involve the dorsal hand on the radial side, specifically the first web space. A characteristic deformity in such cases is wrist drop. If the radial nerve’s deep branch is injured, such as in radial head dislocations, wrist extension is typically preserved due to intact extensor carpi radialis longus function, with only thumb and finger extension impaired. In these cases, no sensory deficits occur in the hand.

Radial nerve injuries resulting from humeral fractures are often due to compression or contusion. Initial management involves reduction and fixation of the fracture, with observation for 2–3 months. Recovery of the brachioradialis function suggests progress. If no recovery is observed, surgical exploration may be warranted. For cases with late-stage functional deficits, tendon transfer procedures may be performed to restore wrist, thumb, and finger extension, often yielding satisfactory outcomes.