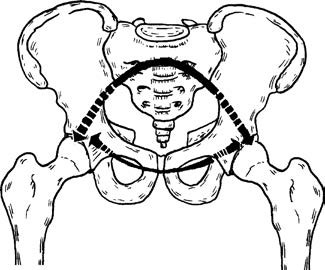

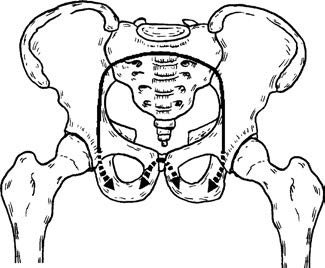

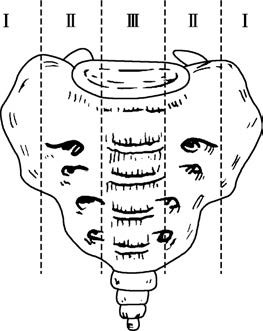

Pelvic fractures refer to the loss of integrity or continuity disruption of the main bones constituting the pelvis and/or the pelvic ring. These account for approximately 3%–8% of all fractures. The pelvis is composed of the bilateral ilium, pubis, and ischium, as well as the sacrum and coccyx posteriorly. Together, the pubic symphysis at the front and the sacroiliac joints at the back form the pelvic ring, which is stabilized by surrounding muscles and ligaments to protect pelvic organs. In an upright position or sitting position, the weight of the torso is transmitted through the sacro-femoral and sacro-ischial arches to the lower limbs or the ischial tuberosities. Additionally, there are two linking secondary arches: one connects the sacro-femoral arch via the superior pubic ramus and pubic symphysis to the bilateral hip joints; the other connects the sacro-ischial arch via the ischial ramus and pubic symphysis to the bilateral ischial tuberosities. Pelvic fractures often begin in the secondary arches, followed by the primary arches, and severe cases may involve injuries to pelvic organs, blood vessels, or nerves.

Figure 1 Sacro-femoral arch and its associated accessory arch

Figure 2 Sacro-ischial arch and its associated accessory arch

Etiology

These injuries often result from high-energy trauma, such as car accidents, crush injuries, and falls from great heights. Low-energy trauma is more commonly seen in elderly individuals who fall from a standing position, young athletes experiencing avulsion fractures during sports, or straddle injuries.

Classification

Pelvic fractures are commonly classified based on fracture location, stability, or the direction of the injuring force.

Classification by Fracture Location

Avulsion Fractures of Pelvic Margins

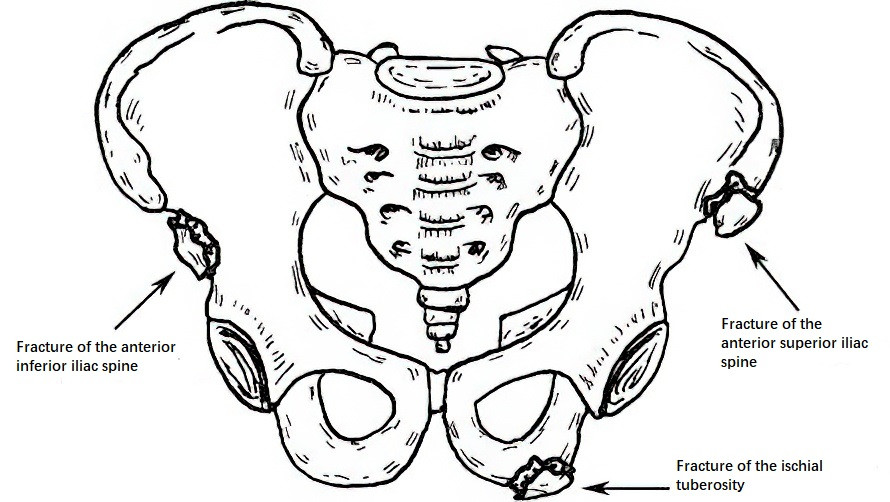

Sudden muscle contraction leads to avulsion fractures at muscle attachment sites along the pelvic margins. The structural integrity and stability of the pelvic ring remain normal, and these injuries are more common in adolescents during sports activities. Common types include:

- Avulsion fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine—caused by sudden contraction of the sartorius muscle;

- Avulsion fracture of the anterior inferior iliac spine—caused by sudden contraction of the rectus femoris muscle;

- Avulsion fracture of the ischial tuberosity—caused by sudden contraction of the hamstring muscles.

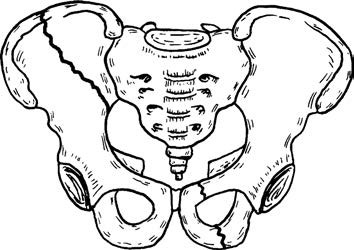

Figure 3 Avulsion fractures of the anterior superior/inferior iliac spine or ischial tuberosity

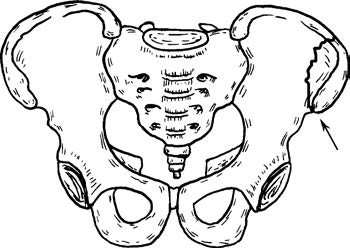

Iliac Wing Fractures

These are usually caused by lateral compression forces. Displacement is often minimal, and comminuted fractures may occur. Isolated iliac wing fractures do not affect the integrity of the pelvic ring.

Figure 4 Iliac wing fracture

Sacrococcygeal Fractures

Sacral Fractures

Dennis' classification is commonly used:

- Zone I: Fracture of the sacral ala, lateral to the sacral foramina.

- Zone II: Fracture involving the sacral foramina.

- Zone III: Fracture medial to the sacral foramina, involving the sacral canal.

Sacral fractures can cause injuries to the lumbosacral nerve roots or the cauda equina.

Figure 5 Zonal classification of the sacrum

Coccygeal Fractures

These are often caused by falls directly onto the seated position. They are frequently accompanied by fractures at the terminal end of the sacrum, with minimal displacement.

Pelvic Ring Fractures

Single-site fractures of the pelvic ring are rare; multiple fractures are more common, including:

- Bilateral fractures of the superior and inferior pubic rami;

- Unilateral fractures of the superior and inferior pubic rami with separation of the pubic symphysis;

- Fractures of the pubic rami with sacroiliac joint dislocation;

- Fractures of the pubic rami with iliac fractures;

- Iliac fractures with sacroiliac joint dislocation;

- Separation of the pubic symphysis with sacroiliac joint dislocation.

Figure 6 Schematic illustration of double-site fractures of the pelvic ring

Posterior dislocations of the sacroiliac joint are more common than anterior dislocations, where the ilium dislocates anteriorly to the sacrum. Anterior dislocations are more often observed in children. These injuries are typically caused by high-energy trauma such as traffic accidents or falls from great heights and are often associated with pelvic deformity and complications.

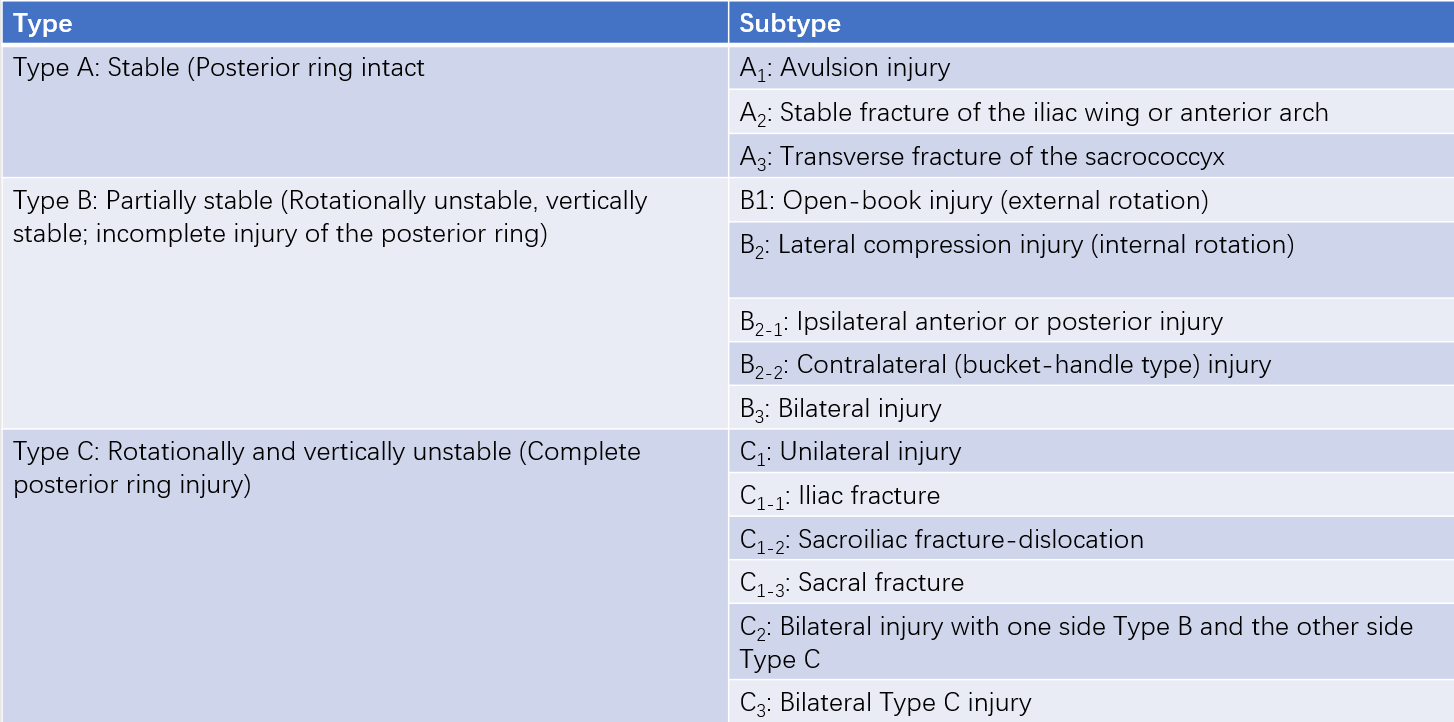

Classification by Stability (Tile Classification)

The Tile classification categorizes pelvic fractures based on the stability of the pelvic ring and divides injuries into three types.

Table 1 Tile classification of pelvic ring injuries

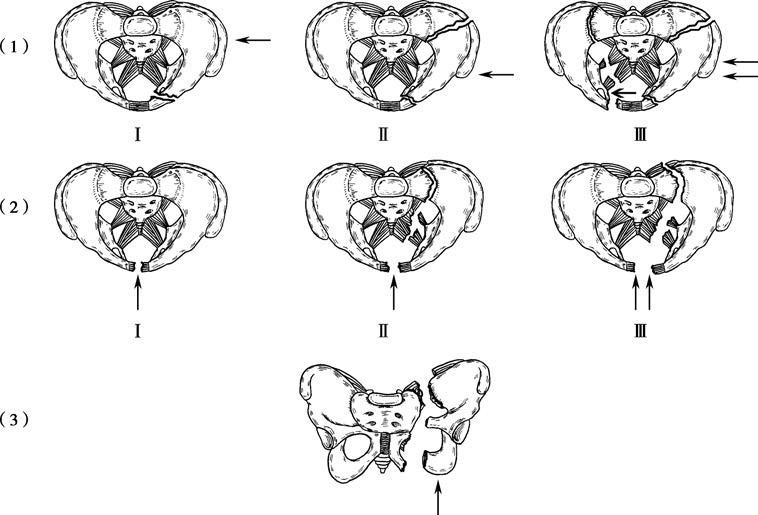

Classification by Direction of Force (Young and Burgess Classification)

Young and Burgess classify pelvic fractures into four types based on the direction of the injuring force:

Figure 7 Classification of pelvic fractures (Young-Burgess classification, arrows indicate force direction)

(1) LC fractures (Lateral Compression; Types I, II, III)

(2) APC fractures (Anteroposterior Compression; Types I, II, III)

(3) VS fractures (Vertical Shear)

Lateral Compression (LC) Fractures

Lateral forces compress the pelvis inwardly; oblique fractures of the pubic rami and posterior pelvic injuries are commonly observed on either the ipsilateral or contralateral side. LC fractures account for approximately 38.2% of cases.

Anteroposterior Compression (APC) Fractures

Anterior forces directly impact the pelvis or are transmitted indirectly via the lower extremities, causing external rotation injuries of the pelvis. Common findings include separation of the pubic symphysis or vertical fractures of the pubic rami, accounting for approximately 52.4% of cases.

Vertical Shear (VS) Fractures

These result from vertical or longitudinal forces. Typical findings include separation of the pubic symphysis or vertical fractures of the pubic rami, complete dislocation of the sacroiliac joint, vertical fractures of the ilium and sacrum, or upward and backward displacement of the hemipelvis. The probability of associated neurovascular injuries is high, with VS fractures accounting for approximately 5.8% of cases.

Combined Mechanical (CM) Fractures

These account for approximately 3.6% of cases and may involve combinations such as LC/VS or LC/APC fractures. LC/APC Type III fractures and VS fractures are the most severe, with a high rate of complications. Further discussion will focus on LC/APC Type III and VS fractures.

Clinical Presentation

Pain accompanied by restricted mobility is common, with a history of significant traumatic force. These injuries are often associated with severe polytrauma and shock. Open fractures are more severe, with mortality rates as high as 40%–70%.

Positive Pelvic Distraction and Compression Tests

During the distraction test, outward pressure is applied to the bilateral iliac crests, causing separation of the anterior pelvic ring; pain at the site of injury indicates a positive result. During the compression test, inward pressure is applied to the iliac crests, with pain at the site of injury indicating a positive result. Crepitus may occasionally be detected during these tests.

Figure 8 Pelvic compression and distraction tests

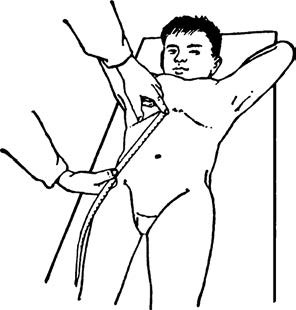

Leg Length Asymmetry

Differences in leg lengths may be observed by measuring the distance between the xiphoid process and the bilateral anterior superior iliac spines, with upward displacement making one side shorter. Distances between the umbilicus and medial malleoli may also be measured.

Figure 9 Measurement of the distance between the xiphoid process of the sternum and the anterior superior iliac spine

Localized Swelling, Skin Abrasions, or Subcutaneous Hematoma

Severe cases may exhibit Morel-Lavallée lesions. Perineal bruising is a distinctive sign of pubic and ischial fractures.

Imaging Examinations

Anteroposterior and inlet/outlet X-rays of the pelvis can reveal the type of fracture and the degree of displacement of bone fragments. CT scans provide clearer images and allow for accurate assessment of sacroiliac joint integrity and associated injuries to the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Three-dimensional reconstruction via CT offers a more intuitive and spatially accurate representation of the fracture type and direction of displacement.

Complications

Pelvic fractures are frequently accompanied by severe complications, which are often more serious than the fracture itself and warrant careful attention. Common complications include:

Retroperitoneal Hematoma

Fractures can lead to extensive bleeding. Large hematomas may spread through loose connective tissues in the retroperitoneal space, reaching the root of the mesentery, renal area, and subphrenic region, and may also extend anteriorly toward the lateral abdominal wall. If major retroperitoneal arteries or veins are involved, rapid deterioration and death may occur.

Injuries to Pelvic Organs

These include injuries to the bladder, posterior urethra, and rectum, with urethral injuries occurring more frequently than bladder injuries. Displacement of pubic rami fractures may result in urethral trauma and perineal lacerations, and can also cause rectal injuries or vaginal wall tears. Rectal rupture may lead to diffuse peritonitis and perirectal infections.

Nerve Injuries

The lumbosacral plexus and sciatic nerve are commonly affected. Lumbosacral plexus injuries often involve preganglionic avulsion, which is associated with a poor prognosis. Sacral fractures in zones II and III are more likely to cause damage to the lumbosacral nerve roots. Injury to the sacral nerves may result in dysfunction of the sphincter muscles.

Fat Embolism and Venous Embolism

Rupture of pelvic venous plexuses may lead to fat embolism, with an incidence of 35%–50%. Symptomatic pulmonary embolism occurs in 2%–10% of cases, while fatal pulmonary embolism is reported in 0.5%–2% of cases.

Emergency Management of Pelvic Fractures

Monitoring of Vital Signs

In cases of hemodynamic instability, prompt management of shock is essential. Establishing intravenous access for rapid blood transfusion and fluid resuscitation is necessary to stabilize vital signs and hemodynamics, preferably via the upper limbs or cervical access.

Diagnostic Imaging and Assessment

Depending on the clinical condition, early completion of X-ray, CT, and ultrasound examinations is important to identify any associated injuries. Life-threatening complications must be addressed first. If signs of peritoneal irritation (e.g., abdominal pain, distension, muscle guarding) are present, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration may be performed. Urine output and urination status should be evaluated. If injuries to vital abdominal or pelvic organs or the urinary tract are suspected, relevant specialties should be consulted promptly. During abdominal surgery, retroperitoneal hematomas should not be opened. Perineal and rectal lacerations require timely repair; in some cases, vaginal packing may be used for hemostasis, and a transverse colostomy may be necessary. In cases of open-book pelvic injuries, pelvic binders, bed sheets, or external fixation devices can help reduce pelvic volume and increase retroperitoneal pressure to control bleeding. If hypotension persists despite rapid transfusion and fluid resuscitation, and facilities are available, emergency interventional procedures such as unilateral or bilateral internal iliac artery embolization may be performed. In the absence of angiographic equipment and when patient transfer is not feasible, direct pelvic packing may be performed to save the patient’s life, followed by admission to a surgical intensive care unit.

Management of Pelvic Fractures

Stable Pelvic Fractures (Tile Type A)

Non-displaced fractures are typically managed conservatively. Minimally displaced fractures, such as avulsion fractures of the anterior superior/inferior iliac spine, ischial tuberosity, or iliac wing, are also treated conservatively with bed rest for 3–4 weeks. For fractures with significant displacement that may impair function, open reduction with internal fixation or closed reduction with percutaneous fixation may be considered.

Sacrococcygeal Fractures

Isolated sacrococcygeal fractures that do not affect pelvic ring stability are generally treated conservatively, with early bed rest. Once pain improves, mobilization may begin. In cases of significantly displaced coccygeal fractures (e.g., anterior displacement causing rectal irritation or difficulty defecating), closed reduction via digital rectal manipulation may be attempted. If this fails and symptoms persist, surgical reduction and fixation may be considered.

Unstable Pelvic Fractures (Tile Type B and C)

These injuries require restoration of the integrity and stability of the pelvic ring. Open reduction and internal fixation with plates and screws is commonly performed, sometimes supplemented by external fixation. Conventional open surgery for pelvic fractures can cause additional trauma, significant intraoperative bleeding, and a high rate of postoperative complications. Minimally invasive surgical approaches are becoming the standard, with the use of navigation systems and orthopedic robots enhancing the precision and reliability of fracture reduction and fixation. These advancements are especially beneficial for elderly patients with pelvic fractures.