Anatomical Overview

The calcaneus is the largest tarsal bone, composed primarily of cancellous bone, and has an irregular cuboidal shape with a slight arch. The posterior part of the calcaneus serves as one of the load-bearing points of the foot arch. It articulates with the talus to form the subtalar joint. The sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus supports the talar head and bears body weight by contacting the talar neck. The superior articular surface of the calcaneus, together with the distal talus, forms the subtalar joint; the calcaneus also articulates with the cuboid bone at the calcaneocuboid joint.

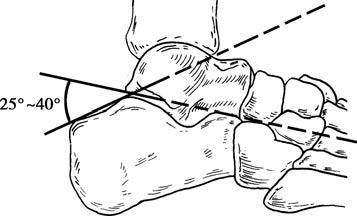

Figure 1 Böhler angle of the calcaneal tuberosity

The Böhler angle is defined as the angle formed by the intersection of lines drawn from the highest point of the posterior articular surface to the calcaneal tuberosity and the highest point of the anterior process. A normal Böhler angle ranges from approximately 25° to 40°. The calcaneal tuberosity, along with the heads of the first and fifth metatarsals, constitutes the three main weight-bearing points of the foot, which contribute to the structural integrity of the foot arch. A fracture or collapse of the calcaneus alters this tri-point loading configuration, potentially causing arch collapse, changes in gait, and a reduction in the foot's elasticity and shock absorption capacity.

Etiology and Classification

Calcaneal fractures most commonly occur due to falls from height with landing on the heels, often leading to compression or splitting of the bone. These fractures account for 2.9% of all fractures and 30.3% of foot fractures. Variations in the mechanism of injury, point of force application, and preexisting bone quality result in different types of calcaneal fractures.

The Sanders classification system categorizes fractures based on coronal CT images of the posterior articular surface of the calcaneus. This system classifies fractures according to the number and location of fracture fragments involving the posterior facet:

- Type I: Non-displaced fractures, regardless of the number of fracture lines.

- Type II: Two-part fractures involving the posterior facet.

- Type III: Three-part fractures of the posterior facet.

- Type IV: Fractures involving four or more fragments of the posterior facet.

In cases of severe comminuted fractures where the largest bone fragment is less than 3 cm in its greatest dimension, the injury is considered a calcaneal osseous crush injury.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Following a fall, patients often experience heel pain, swelling, subcutaneous bruising, a flattened foot sole, and localized deformity, with an inability to bear weight. Localized tenderness is typically present in the heel region, and a noticeable increase in the width of the calcaneus compared to the uninjured side suggests a possible fracture.

Anteroposterior, lateral, and axial (Harris) X-ray views of the ankle and calcaneus can confirm the presence, type, and degree of displacement of the fracture. Given that axial force from a fall may be transmitted upward through the lower extremity to the pelvis and spine, it is important to evaluate for associated symptoms in the hip and spinal regions and to perform radiographic examination in these areas to avoid missed diagnoses.

Treatment

The principles of treatment for calcaneal fractures focus on restoring the alignment of the subtalar joint, maintaining the Böhler angle, correcting the widening of the calcaneus, and preserving the normal height of the foot arch and weight-bearing relationship. For extra-articular fractures that do not involve the subtalar joint, such as minimally displaced fractures of the anterior calcaneus, tuberosity fractures, or undisplaced sustentaculum tali fractures, immobilization with a cast for 4 weeks is typically sufficient before initiating functional rehabilitation. Large displaced sustentaculum tali fractures may require open reduction and internal fixation through a medial approach. For significantly displaced calcaneal body fractures, closed reduction with external fixation may be attempted; otherwise, open reduction and internal fixation are considered. Beak-like fractures of the calcaneal tuberosity can be treated with closed reduction and leverage or open reduction, followed by fixation with cancellous screws, allowing early ankle mobilization. Intra-articular fractures involving the subtalar joint aim to achieve anatomical realignment as the primary goal.

Non-Surgical Management

This approach is suitable for undisplaced or minimally displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures, as well as for patients with significant displacement who are elderly or have severe systemic conditions. Immobilization with a cast or brace is given for 4 to 6 weeks, while active movement of lower limb joints is encouraged to prevent deep vein thrombosis and muscle atrophy. Partial weight-bearing with the assistance of crutches can generally commence around the 10th week, progressing to full weight-bearing after 12 weeks. Return to work is often achieved within 4 months.

Closed Reduction with Leverage Method

Under fluoroscopic guidance using a C-arm X-ray machine, two large Kirschner wires are inserted parallel to each other at the Achilles tendon insertion site, extending into the area beneath the posterior articular surface. While the knee is flexed and the ankle plantarflexed, the collapsed posterior articular surface is elevated. For widened calcaneal fractures, lateral compression is employed. With satisfactory positioning confirmed using lateral and axial X-ray projection, the Kirschner wires and cast are used for fixation. Removal of the wires and cast occurs 6 weeks later, followed by exercises to regain ankle mobility.

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF)

This surgical option is indicated for fractures with significant displacement of the posterior articular surface, avulsion fractures of the calcaneal tuberosity, and fractures with severe displacement of the calcaneal body even without joint surface displacement. The goal is to reduce the likelihood of long-term complications by restoring anatomical alignment through open reduction and internal fixation.

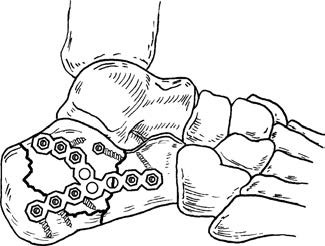

Figure 2 Open reduction and internal fixation with plate for calcaneal fracture

Minimally Invasive Open Reduction with Anatomical Plates and Screws

Conventional surgeries often utilized an L-shaped incision, which carried higher risks of soft-tissue necrosis and infection. Moreover, conventional fixation devices lacked sufficient compressive capability and failed to adequately restore calcaneal width. Modern techniques utilize small posterior-lateral incisions with the application of anatomical plates and cortical screws for compression fixation. These approaches reduce the risk of soft-tissue necrosis and infection while effectively correcting the widened deformity, resulting in favorable treatment outcomes.

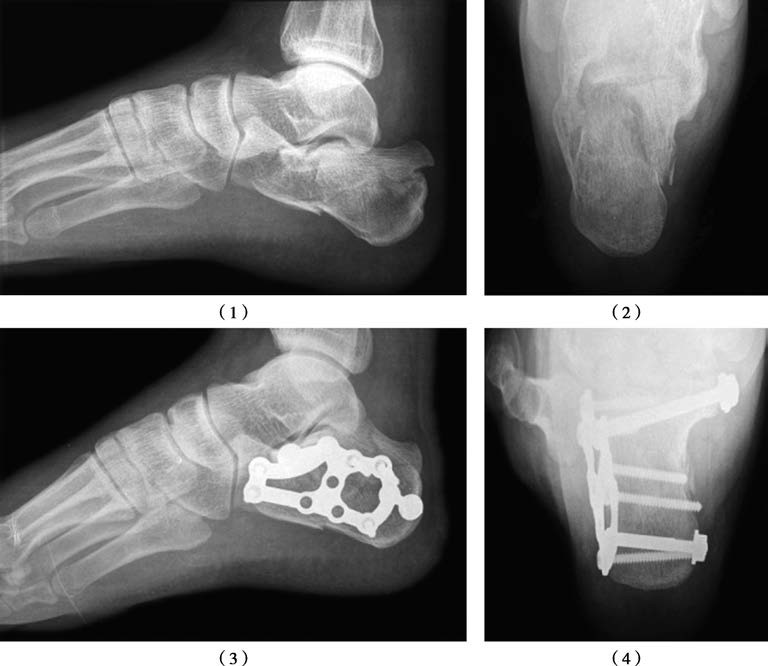

Figure 3 Minimally invasive open reduction and anatomical plate with bone peg compression internal fixation for calcaneal fracture

(1) Preoperative Lateral X-ray Image

(2) Preoperative Axial X-ray Image

(3) Postoperative Lateral X-ray Image

(4) Postoperative Axial X-ray Image

Arthrodesis

For cases of severe comminuted fractures where reconstructing the joint surface anatomically through surgery proves challenging, and non-surgical treatment leaves a high likelihood of residual deformity, subtalar joint fusion during the same surgical session can be considered. This approach restores calcaneal anatomy while reducing treatment duration and enabling earlier return to work. However, current debates persist on whether to perform a single-stage fusion or to opt for initial open reduction and internal fixation followed by fusion at a later stage as necessary.