Anatomical Overview

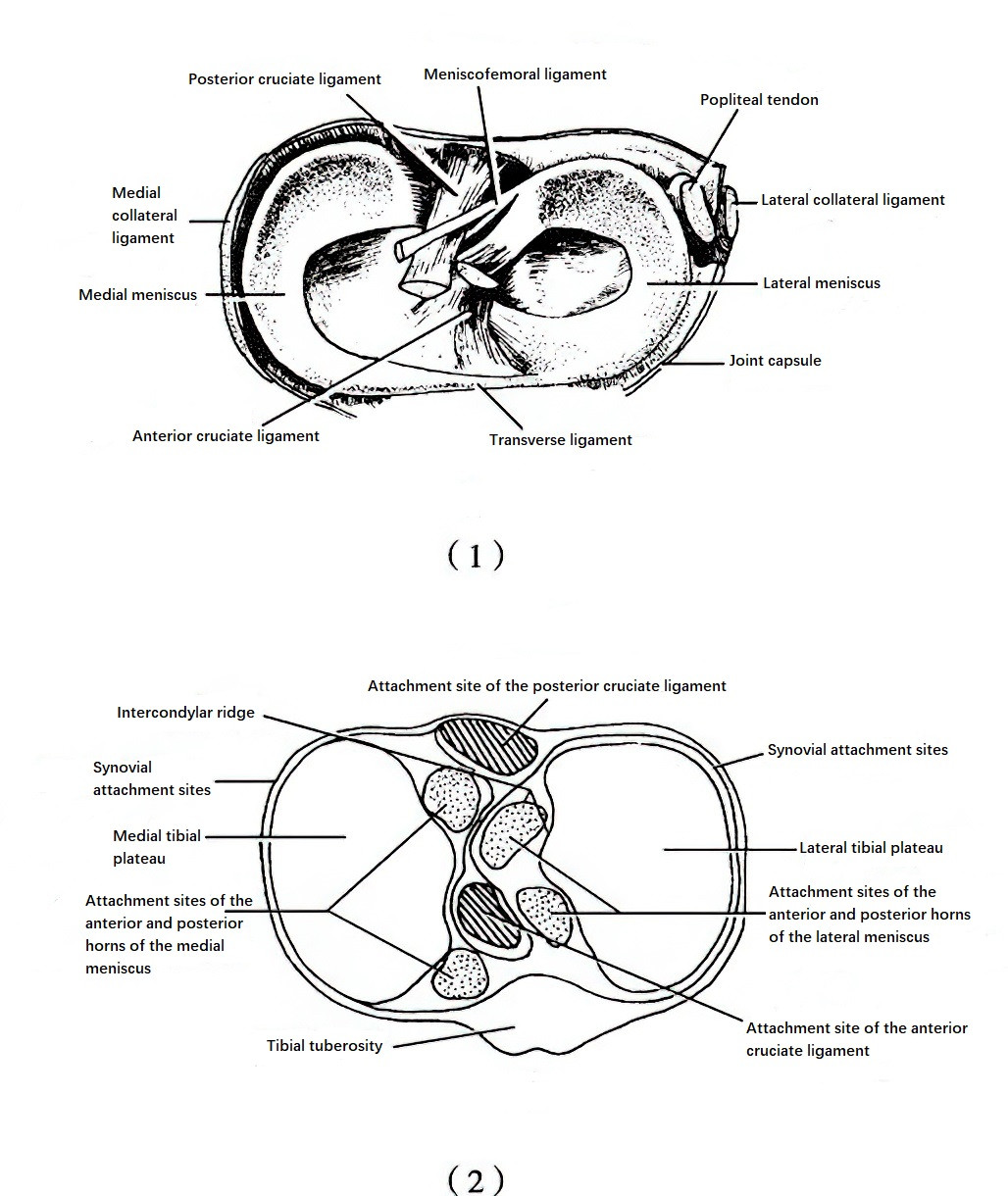

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous structure that occupies the space between the femur and tibia. Its superior surface, which contacts the femoral condyles, is slightly concave, while the inferior surface, which rests on the tibial plateau, is flat. Each knee joint contains two menisci: a medial and a lateral one.

The medial meniscus is C-shaped. Its anterior horn is narrow and attaches anterior to the tibial insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), while the broader posterior horn is fixed posterior to the tibial intercondylar eminence. The outer edge of the body of the medial meniscus connects to the deep fibers of the medial collateral ligament, resulting in limited mobility.

Figure 1 Anatomy of the knee meniscus

(1) Superior view of the knee meniscus

(2) Attachment sites of the anterior and posterior horns of the medial and lateral menisci, as well as the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.

The lateral meniscus is O-shaped. Its anterior horn attaches lateral to the ACL insertion, anterior to the lateral tibial intercondylar eminence, and the posterior horn attaches posterior to the intercondylar eminence. The body does not connect to the lateral collateral ligament, and a gap for the popliteus tendon exists in the posterior segment, granting greater mobility to the lateral meniscus.

During development, the meniscus may exhibit an oval-shaped abnormality that covers a larger area of the tibiofemoral surface, referred to as a discoid meniscus. This type is more prone to tearing even with minor trauma.

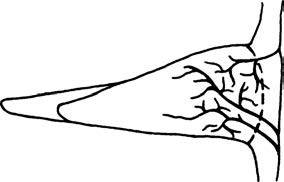

The outer portion of the meniscus (about 10%–30%) is thicker and attaches to the edge of the tibial plateau, receiving blood supply from the synovial membrane. The central portion is thinner and lacks blood supply, relying mainly on synovial fluid for nutrition. Based on vascularization, the meniscus is divided into three zones: red-red (fully vascularized), red-white (partially vascularized), and white-white (avascular). Tears in the red-red zone heal well, those in the red-white zone have moderate healing potential, while those in the white-white zone have poor healing capacity.

Figure 2 Schematic illustration of meniscal blood supply

Functions of the meniscus include:

- Filling the joint space between the femur and tibia to help stabilize the knee;

- Bearing weight and absorbing shock;

- Spreading synovial fluid for joint lubrication;

- Assisting with knee flexion, extension, and rotational movements.

Rotational movements are most likely to cause meniscal tears.

Mechanism and Pathology of Injury

When the knee is extended, the collateral ligaments are tense, the joint is stable, and rotational movement is restricted. During knee flexion, the contact area between the femoral condyles and meniscus decreases. Rotational forces applied in this position may easily lead to meniscal tears due to grinding stress.

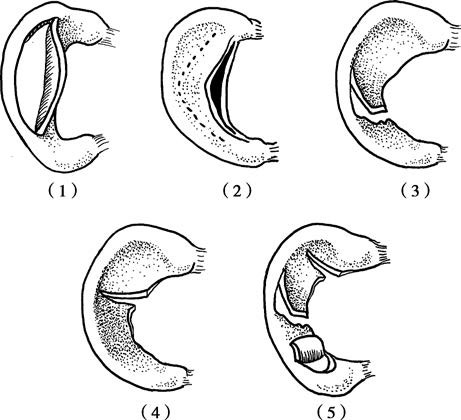

Figure 3 Types of meniscal tears

(1) Longitudinal tear (bucket-handle tear)

(2) Horizontal tear

(3) Oblique tear

(4) Radial tear

(5) Complex tear (composite tear)

Meniscal tears can be classified by morphology as follows:

- Longitudinal tears;

- Horizontal tears;

- Oblique tears;

- Radial tears;

- Complex types, including flap tears, combined tears, and degenerative meniscal tears.

A long, full-thickness longitudinal tear may result in an unstable central flap of tissue. If this flap displaces into the intercondylar notch, the condition is referred to as a "bucket-handle tear."

Clinical Manifestations

Some cases of acute injury are associated with a history of trauma, while the majority do not present a clear history of trauma.

This is more commonly observed in athletes and manual laborers, with men being affected more frequently than women.

Most patients experience joint line pain, which may worsen with joint movement. Pain is more pronounced in red-zone tears of the meniscus and may be accompanied by intra-articular bleeding and restricted movement. Chronic stages can result in recurrent joint swelling, and unstable tissue may cause symptoms such as joint clicking or locking.

Typical signs include tenderness along the joint line, with the location of the tender point often indicating the site of meniscal injury. Bucket-handle tears leading to joint locking often result in restricted knee flexion and extension. Chronic injuries may lead to quadriceps muscle atrophy and weakness.

Special Tests

Hyperextension and Hyperflexion Tests

Mild hyperextension or extreme flexion of the knee may result in pain due to the stretching or compression of the meniscal tear.

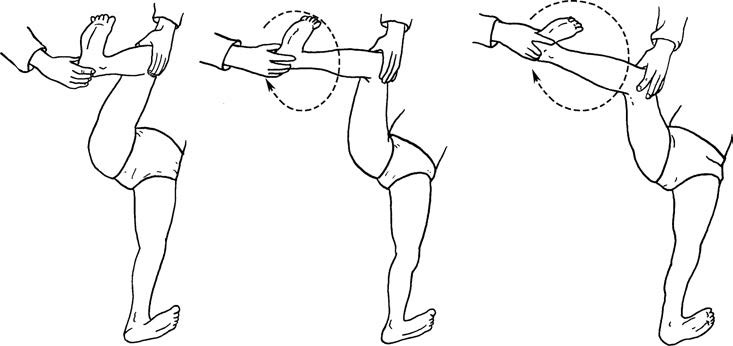

McMurray Test (Meniscal Rotation-Compression Test)

The patient lies supine with the affected knee fully flexed. The examiner places one hand on the joint line for palpation and holds the heel with the other hand. Applying internal rotation and varus forces while gradually extending the knee induces pain, suggesting lateral meniscus tears. Applying external rotation and valgus forces while extending the knee produces pain, indicating medial meniscus tears. The test may also produce a characteristic "clicking" sound. The angle at which the clicking occurs can help localize the injury, with clicking at full flexion indicating posterior horn damage, clicking at around 90° suggesting body damage, and clicking during slight flexion while maintaining rotation indicating possible anterior horn injury.

Figure 4 Meniscal rotation-compression test (McMurray test)

Apley Test (Grinding Test)

The patient lies prone with the knee flexed at 90°. The examiner applies downward pressure on the lower leg while performing internal and external rotation, creating friction between the femoral and tibial articular surfaces. Pain elicited by this maneuver indicates meniscal injury.

Figure 5 Grinding test (Apley test)

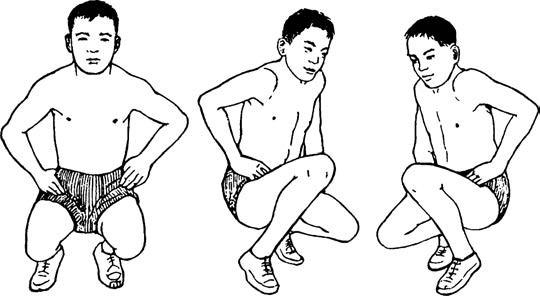

Duck Walking Test

This test is often used to examine for posterior horn damage and is typically suited for adolescents. The patient assumes a squatting position and attempts a duck-like walk with changes in direction. Successfully completing these motions suggests no posterior horn damage. Failure due to pain, inability to fully flex the knee, or the presence of joint clicking and pain is considered a positive result.

Figure 6 Duck walking test

It should be noted that a single positive test alone cannot confirm the diagnosis of a meniscal injury. A comprehensive evaluation that includes clinical symptoms and physical examination findings is essential for reaching the final diagnosis.

Imaging and Arthroscopic Examination

MRI is the preferred method of examination and can clearly reveal whether the meniscus has undergone degeneration, or whether a tear is present. It can also display conditions such as joint effusion and other structural abnormalities. However, its accuracy is inferior to that of arthroscopic evaluation.

Arthroscopic examination allows direct visualization of the integrity and stability of the meniscus and can detect subtle meniscal injuries that are difficult to identify through imaging studies. It also enables simultaneous observation of structures such as the cruciate ligaments, articular cartilage, and synovium. Arthroscopic techniques are not only diagnostic but also therapeutic, allowing procedures such as repair or resection of the torn meniscal tissue to be performed.

Treatment

Acute meniscal injuries can be managed with knee braces or plaster casts for immobilization over a period of four weeks, avoiding weight-bearing activities while concurrently engaging in quadriceps exercises to prevent muscle atrophy. If symptoms persist, surgical treatment is considered. Arthroscopic surgery is currently the preferred approach, with the choice between repair or resection of the torn tissue being guided by the type, location, and condition of the injury. Tears in the red zone should be repaired whenever possible to preserve meniscal function, while tears in the white zone may necessitate partial resection.