Patellar fractures account for 2.6% of adult fractures and may lead to traumatic arthritis or restricted knee joint mobility. The patella plays a critical biomechanical role in knee movement. In the absence of the patella, the patellar ligament lies closer to the center of knee joint motion, shortening the extensor lever arm. As a result, the quadriceps muscle must generate approximately 30% more force to achieve knee extension. Therefore, efforts should be made to restore the integrity of the patella following a fracture.

Anatomical Overview

The patella is the largest sesamoid bone in the human body. It is covered anteriorly by the quadriceps tendon, which continues downward to form the patellar ligament that attaches to the tibial tuberosity. On both sides lie the parapatellar retinacula. The posterior surface contains the articular facet, which forms the patellofemoral joint with the femoral trochlea. Together with surrounding ligaments and retinacula, the patella forms the knee extensor mechanism, an essential structure for knee extension.

Etiology and Classification

Patellar fractures may result from direct trauma or forceful muscular contraction. Direct trauma, such as falling and landing on the knees, often causes comminuted fractures. Strong contraction of the quadriceps muscle—such as when attempting to stabilize the body during a fall—may lead to transverse fractures.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Swelling over the anterior knee typically occurs after injury, and a palpable gap may be present if there is displacement. Anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the knee help determine the location, type, and degree of displacement, which are important for treatment planning. Some studies using MRI and knee arthroscopy have found a relatively high incidence of associated injuries in patients with patellar fractures, including cruciate ligament, collateral ligament, and meniscal injuries. Approximately 6% of these cases may require surgical intervention. It is therefore important to assess for associated injuries to avoid missed diagnoses.

Treatment

Fractures without displacement or with displacement less than 5 mm can be managed non-surgically. The knee is maintained in full extension using a plaster splint or brace for 4–6 weeks. After six weeks, patients begin isometric quadriceps exercises and active knee flexion-extension training. Displacement should be monitored during treatment, as improper external fixation or premature quadriceps activation may worsen the separation.

Surgical intervention is generally recommended when displacement exceeds 5 mm or when the articular surface is disrupted. After open reduction, fixation can be achieved using tension band wiring with Kirschner wires or cerclage wiring. Early knee flexion and extension exercises may be initiated following surgery for simple fractures, while a longer immobilization period is often required for comminuted fractures.

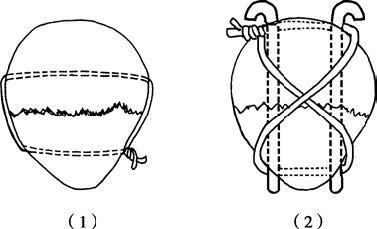

Figure 1 Common internal fixation methods for patellar fractures

(1) Cerclage wire fixation

(2) Tension band wiring with Kirschner wires

For fractures at the superior or inferior pole of the patella, larger fragments may be treated according to the same principles. If the fragments are too small to be fixed, they may be excised. The insertion sites of the quadriceps tendon or patellar ligament can be reconstructed using wires or suture anchors, with the knee immobilized in extension for 4–6 weeks postoperatively. In cases of severe comminuted fractures where cartilage surface reconstruction and stable fixation are not feasible, patellectomy may be performed with repair of the extensor mechanism. Functional rehabilitation typically begins 3–4 weeks after surgery.