Anatomical Overview

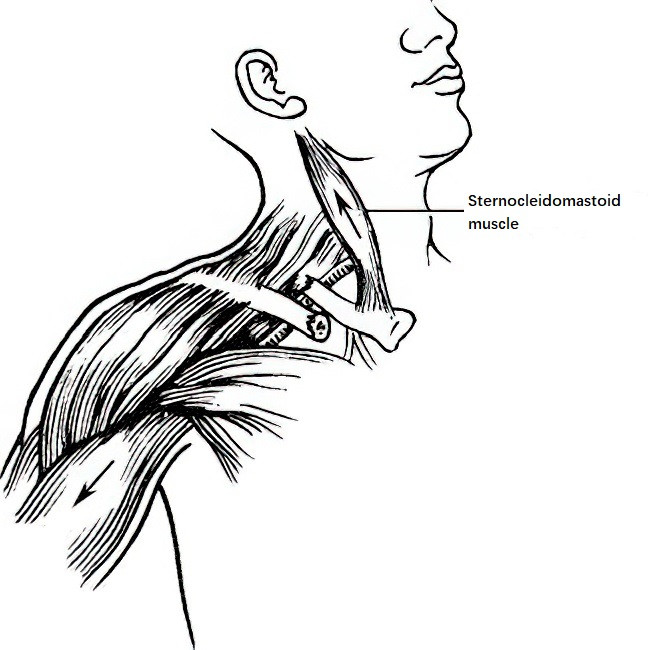

The clavicle serves as the connecting and supporting structure between the upper limb and the trunk. It has an S-shaped curve, with the distal one-third being flattened and convex toward the dorsal side, facilitating the attachment and traction of muscles and ligaments. Its outermost end forms the acromioclavicular joint with the acromion and is stabilized by the coracoclavicular ligament. The proximal one-third is rhomboid-shaped and convex toward the ventral side, forming the sternoclavicular joint with the manubrium through strong ligamentous structures, with the sternocleidomastoid muscle attached in this region.

Etiology and Classification

Clavicular fractures predominantly occur in children and young adults, often resulting from indirect trauma. They account for 5%-10% of all fractures and 44% of shoulder injuries, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1. A common mechanism is falling laterally onto the shoulder, transmitting force to the clavicle and causing an oblique fracture. Alternatively, falling onto an outstretched hand or elbow may transmit force through the shoulder, leading to oblique or transverse fractures. Direct trauma to the clavicle from a blow to the upper chest can cause comminuted fractures, though this is less common. Pediatric clavicular fractures are typically greenstick fractures, while adults more frequently exhibit oblique or comminuted patterns.

Clavicular fractures are classified into three types:

- Type I: Fractures of the middle third (80% of cases). The proximal fragment displaces upward and posteriorly due to traction by the sternocleidomastoid muscle, while the distal fragment shifts anteriorly and inferiorly under the influence of limb gravity and the upper fibers of the pectoralis major muscle, often with overriding.

- Type II: Fractures of the lateral third (15% of cases). The distal fragment displaces inferiorly due to shoulder weight, and the proximal fragment shifts superiorly. Significant displacement should raise suspicion for coracoclavicular ligament injury.

- Type III: Fractures of the medial third (5% of cases). Management requires attention to potential sternoclavicular joint injury.

Figure 1: Common displacement patterns in clavicle fractures

Open clavicular fractures are relatively rare.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The clavicle is located subcutaneously and has a superficial position. A fracture of the clavicle leads to localized swelling and bruising, with aggravated pain during shoulder joint movements. Patients typically support the elbow of the affected side with their uninjured hand to minimize movement of the fracture ends and associated pain. Tilting of the head toward the injured side is often adopted by patients to relieve pain caused by the traction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the proximal fracture end. During an examination, the fracture ends can often be palpated with localized tenderness and crepitus. A diagnosis of a clavicle fracture can commonly be made based on physical examination and symptoms.

In cases of non-displaced fractures or greenstick fractures in children, physical examination alone may sometimes be insufficient for an accurate diagnosis. Anteroposterior X-ray imaging of the shoulder is an essential diagnostic tool. The brachial plexus and subclavian vessels lie posterior to the clavicle. In cases of significant trauma, obvious fracture displacement, or severe local swelling, the possibility of associated injuries—including rib fractures, pulmonary damage, and trauma to the subclavian vessels or brachial plexus—should be considered. Thorough evaluation of the neurological function and blood supply in the upper limb is necessary to accurately diagnose any associated nerve or vascular injuries.

Treatment

Greenstick fractures in children and non-displaced fractures in adults typically do not require special treatment. Immobilization of the affected limb with a sling for 3–6 weeks is sufficient before initiating movement.

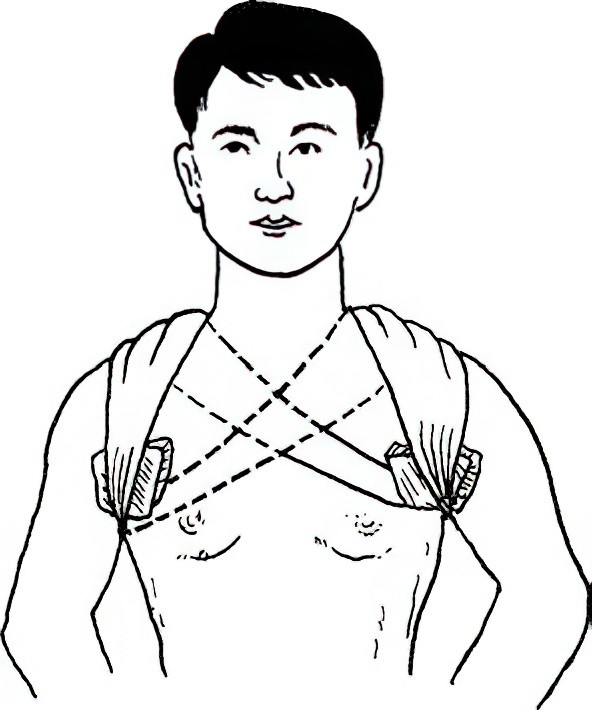

Approximately 80–90% of midshaft clavicle fractures can be managed conservatively using non-surgical methods, involving closed reduction and fixation with a figure-of-eight bandage. Post-treatment monitoring of bilateral upper limb circulation and sensory-motor function is important. Swelling or numbness in the limb may indicate excessive compression from the bandage, necessitating adjustment. About one week after fixation, as local swelling subsides and bandage tension decreases, the bandage may loosen, leading to secondary displacement. Frequent evaluation of the fixation's stability during the first two weeks of treatment allows prompt adjustment to maintain proper fixation.

Figure 2 Figure-of-eight bandage fixation following closed reduction of a clavicle fracture

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) may be considered in specific cases, including: (i) patients unable to tolerate the discomfort of figure-of-eight bandaging; (ii) recurrent displacement following reduction, affecting cosmetic appearance; (iii) associated nerve or vascular injury; (iv) open fractures; (v) nonunion of old fractures; and (vi) lateral clavicle fractures with concurrent coracoclavicular ligament rupture. The choice of internal fixation method depends on the fracture location, type, and displacement severity. When plate fixation is used, the plate should be contoured to match the shape of the clavicle and positioned on the superior surface of the clavicle rather than the anterior surface.

Complications

Complications may include: (i) nonunion; (ii) malunion; (iii) vascular or nerve injury; (iv) post-traumatic arthritis of the acromioclavicular or sternoclavicular joint; and (v) complications associated with surgical treatment, such as wound infection.