Congenital talipes equinovarus (also known as congenital clubfoot) is a common condition in children, significantly affecting the appearance and function of the foot. Its incidence is approximately 0.1%, with a male-to-female ratio of about 2:1.

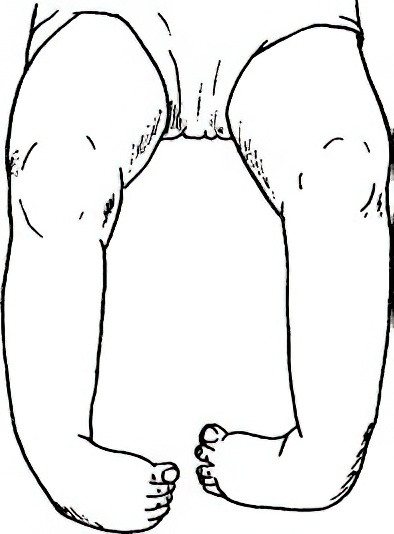

Figure 1 Congenital talipes equinovarus

Etiology

The cause of congenital talipes equinovarus remains unclear and is thought to involve several theories, including abnormal embryonic development, genetic inheritance, and intrauterine developmental arrest of the fetal foot.

Pathology

The primary deformities include:

- Forefoot adduction

- Ankle plantarflexion

- Hindfoot varus

- Secondary internal rotation of the distal tibia

Clinical Presentation

After birth, one or both feet exhibit varying degrees of varus and plantarflexion deformities, forming a clubfoot appearance. In mild cases, the forefoot displays adduction and plantarflexion, with wrinkles appearing on the plantar surface of the foot. Dorsiflexion and abduction of the foot reveal elastic resistance. Cases are generally classified into flexible (extrinsic) and rigid (intrinsic) types.

Flexible deformities are milder, with smaller feet, relatively loose skin and tendons, and a greater ease of manual correction.

Rigid deformities are more severe, with a deep transverse crease on the plantar surface, a small calcaneus, thin and tight Achilles tendon, and pronounced equinovarus-adduction deformities that are difficult to correct manually.

When children begin to walk, weight-bearing occurs on the lateral edge of the affected foot, leading to an unstable gait and limping as the deformity worsens. Calluses and bursae can develop at weight-bearing areas on the dorsum of the foot, and internal rotation of the tibia becomes more pronounced. Muscular atrophy is frequently observed in the affected lower leg compared with the unaffected side.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally straightforward due to the apparent deformities, including forefoot adduction, hindfoot varus, ankle equinus, and associated tibial internal rotation. However, mild cases in newborns may be overlooked when forefoot adduction and plantarflexion are not prominent. The simplest diagnostic method involves moving the forefoot in all directions by hand. Resistance with elastic recoil during eversion and dorsiflexion indicates the need for further evaluation to confirm the diagnosis and initiate early treatment. X-rays are not usually required for diagnosis but are valuable for determining the severity of varus and equinus deformities, as well as for assessing therapeutic outcomes.

Differential Diagnosis

Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita

This condition involves multiple joint deformities in the limbs, with fixed and difficult-to-correct contractures and early bony changes.

Cerebral Palsy

Spastic paralysis, hypertonia, increased reflexes, pathological reflexes, and other signs indicative of cerebral involvement are observed.

Post-Poliomyelitis Syndrome

Muscle paralysis and atrophy are present as residual effects of poliomyelitis.

Treatment

The treatment goals include deformity correction, muscle balance restoration, and functional recovery. The principles of management focus on early diagnosis, early intervention, individualized treatment approaches, and recurrence prevention. Non-surgical methods are preferred, with the neonatal period offering the best opportunity for treatment. Early intervention generally produces favorable results.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Ponseti Method

This internationally recognized treatment is typically initiated within 5–7 days of birth and involves two phases:

- Phase 1: Application of specialized manual correction techniques, serial plaster cast fixation, and percutaneous Achilles tenotomy to achieve complete correction of the deformity.

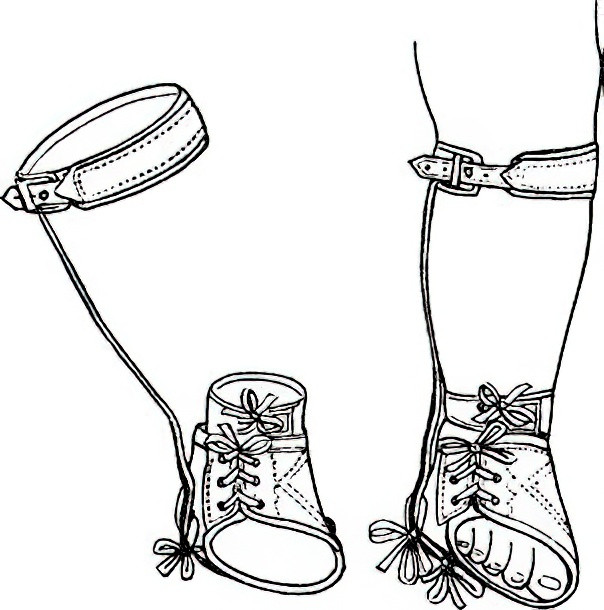

- Phase 2: Following full correction, use of a foot abduction brace is required until the age of 4 years to prevent recurrence. The Ponseti method is most effective when started before 9 months of age.

Manual Manipulation

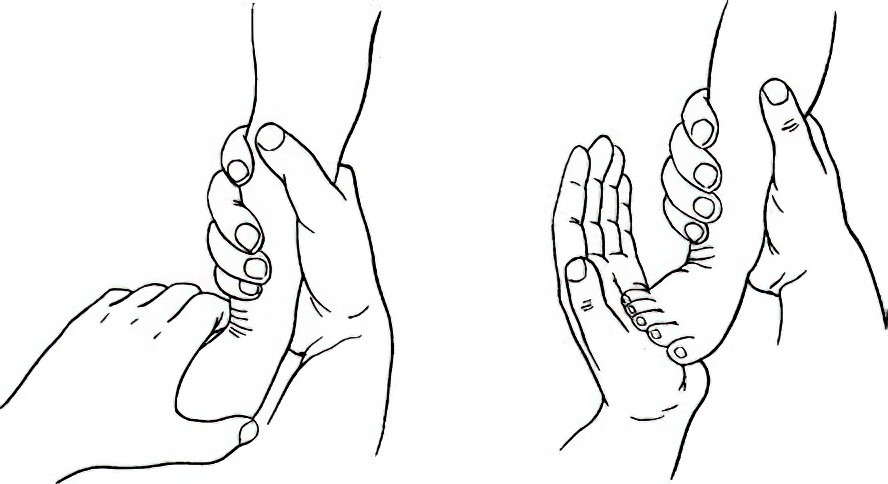

This is suitable for infants under 1 year of age, with parents performing manipulation under medical guidance. During correction, the affected foot is positioned in eversion, abduction, and dorsiflexion, performed twice daily. The manipulation should be gentle to avoid injury, with corrections made to an appropriate degree. After deformity correction, soft bandages are applied, wrapping from the medial plantar side to the dorsolateral side of the foot to secure it in the corrected position. Once significant improvement is observed, and elastic resistance to dorsiflexion and abduction is reduced, an orthotic foot brace is used to maintain the corrected position. The treatment should continue until after the child reaches 1 year of age. Even if complete correction is not achieved, this method relaxes spastic soft tissues, preparing for further treatment.

Figure 2 Manual manipulation of the deformity

Figure 3 Orthotic foot brace

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is considered for unsatisfactory outcomes of non-surgical methods or recurrent deformities, with the optimal surgical age ranging from 6 to 18 months. Soft tissue surgery is most commonly performed, focusing on soft tissue release and muscle force balance. Common surgical procedures include:

- Achilles tendon lengthening

- Medial foot soft tissue release

- Plantar aponeurotic release

- Posterior ankle capsulotomy

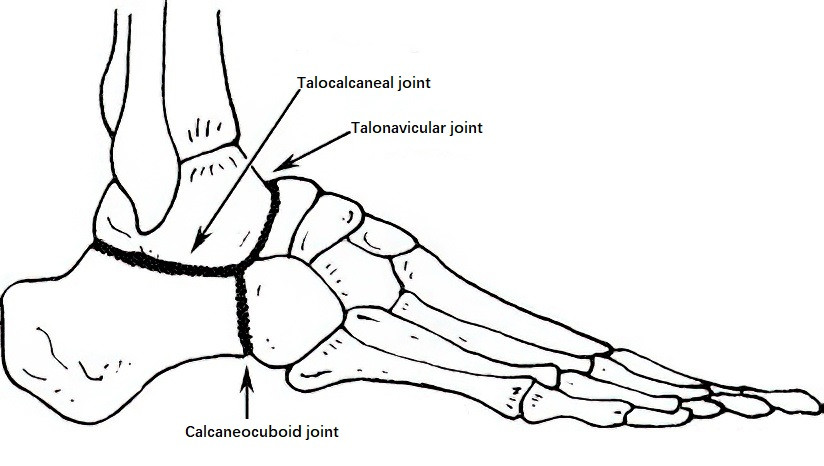

Figure 4 Triple arthrodesis

Postoperatively, long-leg tubular casts are typically applied for 2–3 months.

Bone surgeries are generally avoided before the age of 10 to prevent damage to growth plates and subsequent developmental disruptions. In patients older than 10 years with residual deformities, osteotomy may be performed to correct foot deformities. Procedures such as triple arthrodesis (fusion of the talocalcaneal, talonavicular, and calcaneocuboid joints) or other osteotomies may be considered.