Developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH), previously referred to as congenital dislocation of the hip, primarily arises from structural abnormalities of the acetabulum, proximal femur, and joint capsule, which lead to joint instability and eventually the dislocation of the hip. Some scholars also refer to it as developmental dysplasia of the hip. The incidence ranges from 0.1% to 0.4%, varying significantly across different ethnic groups and regions. It occurs more often in females than in males, with a ratio of approximately 6:1. The left hip is more frequently affected than the right, and bilateral cases are relatively common.

Etiology

The exact cause remains unclear. Primary acetabular dysplasia and ligament laxity are key factors contributing to hip dislocation. The condition is associated with ethnicity, geography, genetic abnormalities, and endocrine factors. Approximately 20% of affected children have a family history, indicating a genetic component. The condition is also associated with breech presentation during delivery, with clinical statistics showing a higher incidence in such cases. Lifestyle and environmental factors also play a role, as regions where infants are traditionally swaddled with restricted lower limb movement show a significantly increased incidence.

Pathology

The primary pathological changes vary with age and can be classified into pre-standing and dislocation phases.

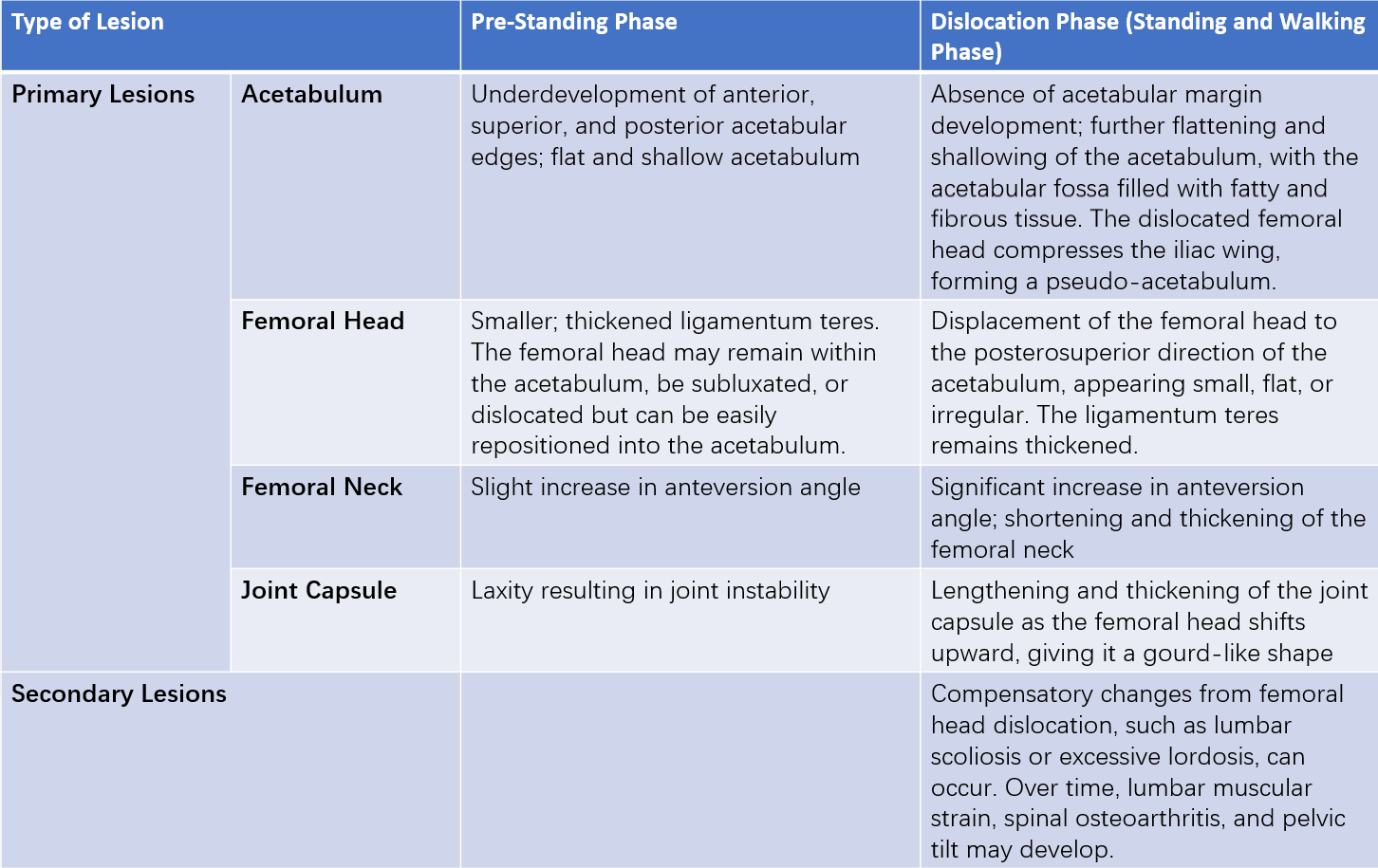

Table 1 Pathological changes in developmental dislocation of the hip (DDH)

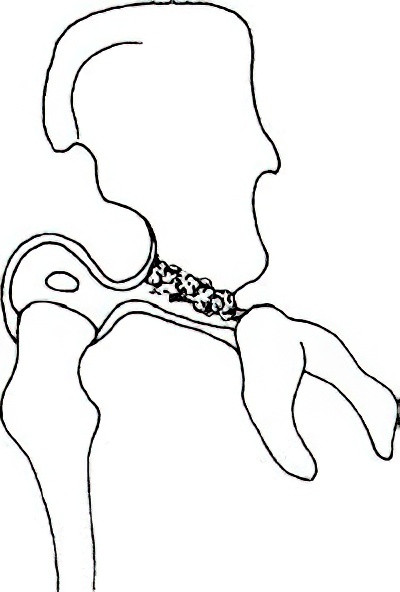

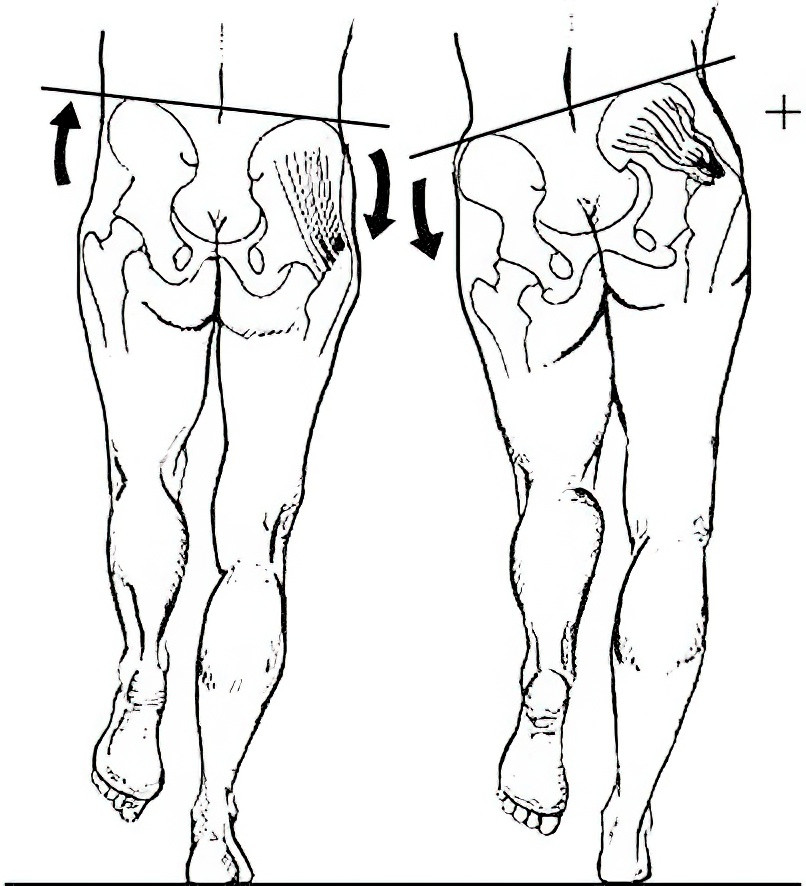

Figure 1 Pathological changes during the dislocation phase of developmental dislocation of the hip.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Pre-Standing Phase

The clinical presentation of developmental dislocation of the hip varies significantly based on the child’s age. In newborns and infants, symptoms are not obvious during the pre-standing phase. However, the following signs may suggest the possibility of hip dislocation:

- Asymmetry of thigh skin folds: The skin folds on the inner thigh appear asymmetrical, with deeper and more pronounced folds on the affected side.

- Widening of the perineum: A wider perineal space is noticeable, especially in cases of bilateral dislocation.

- Decreased hip joint mobility on the affected side: There is less movement, with restricted motion, weaker kicking strength compared to the unaffected side, and the hip often remaining in a flexed position that cannot fully extend.

- Shortening of the affected limb: The affected limb may appear shorter.

- Audible or palpable clicking: When the affected limb is pulled, a clicking sound or sensation may occur, and the child might cry or become irritable.

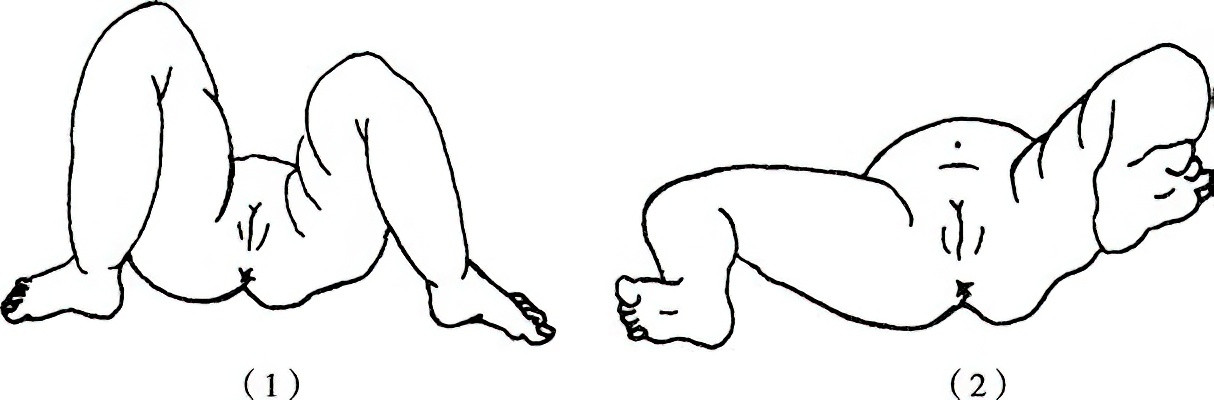

Figure 2 Positive signs and diagnostic tests:

(1) Unequal leg length. The left inner thigh skin folds are increased, and the left buttock exhibits a concave appearance.

(2) The hip flexion-abduction test shows a positive result on the left side, while the right side is normal.

The following diagnostic exams are helpful:

Hip Flexion-Abduction Test

When the hip and knee joints are flexed at 90°, the normal range of abduction in newborns and infants is approximately 80°. A unilateral abduction of less than 70° or an asymmetry in bilateral abduction of ≥20° is considered a positive test, indicating potential dislocation, subluxation, or dysplasia. If a clicking sound is heard during the test and abduction increases to 90°, it suggests a reduction of the dislocated hip.

Allis Sign

With the child lying supine, the knees are flexed to 90°, the legs are aligned side by side, and both medial malleoli are aligned. If the level of the knee joint is lower on the affected side than the unaffected side, the sign is considered positive.

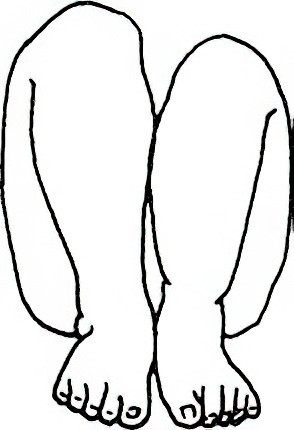

Figure 3 Allis sign

The left knee joint is lower than the unaffected (right) side.

Ortolani Test (Reduction Test)

In the supine position, an assistant stabilizes the pelvis. The examiner places their thumb on the inner upper portion of the femur near the greater trochanter, with the other fingers placed on the outer side of the greater trochanter. The opposite hand flexes the hip and knee to 90°, then gradually abducts the hip while pressing the greater trochanter forward and medially. A palpable or audible "click" is considered a positive result, indicating the dislocated femoral head sliding back into the acetabulum via a lever action.

Barlow Test (Dislocation Test)

In the supine position, the hip and knee are flexed, and the hip is gradually adducted. The examiner uses their thumb to apply pressure on the child’s inner thigh near the lesser trochanter, pushing the femoral head outward and upward. A palpable or audible "click" as the femoral head slides out of the acetabulum indicates a positive sign. Releasing the thumb pressure causes the femoral head to return to the acetabulum, indicating hip joint instability or subluxation.

Dislocation Phase (Standing and Walking Phase)

Children typically begin walking later than those without DDH. With unilateral dislocation, limping may occur. In bilateral dislocation, the pelvis tilts forward, the buttocks protrude, and lumbar lordosis becomes especially pronounced. Children walk with a characteristic waddling gait. While lying supine with both hip and knee joints flexed to 90°, the knees will not align on the same plane bilaterally. When pushing and pulling the affected femur, the femoral head may move up and down, resembling the action of a pump. Adductor muscle tightness and restricted hip abduction are also observed.

Trendelenburg Sign (Single-Leg Stance Test)

In normal cases, when standing on one leg, the gluteus medius and minimus muscles contract to raise the opposite pelvis and maintain balance. In cases of hip dislocation, the gluteus medius and minimus are weak, causing the opposite pelvis to descend instead of rise.

Figure 4 Trendelenburg sign (single-leg stance test).

Imaging Examinations

Ultrasound Examination

With its high sensitivity, ultrasound can detect acetabular developmental abnormalities at an early stage. In recent years, it has been widely accepted for screening and evaluating hip joint development in newborns.

X-Ray Examination

For infants suspected of developmental dislocation of the hip, anteroposterior pelvic radiographs are typically performed after 3 months of age, as the acetabulum is largely cartilaginous before this age. The X-ray may reveal acetabular dysplasia, subluxation, dislocation, a smaller ossification center of the femoral head compared to the unaffected side, or an increased femoral neck anteversion angle.

Figure 5 X-ray showing developmental dislocation of the hip in a child (right side).

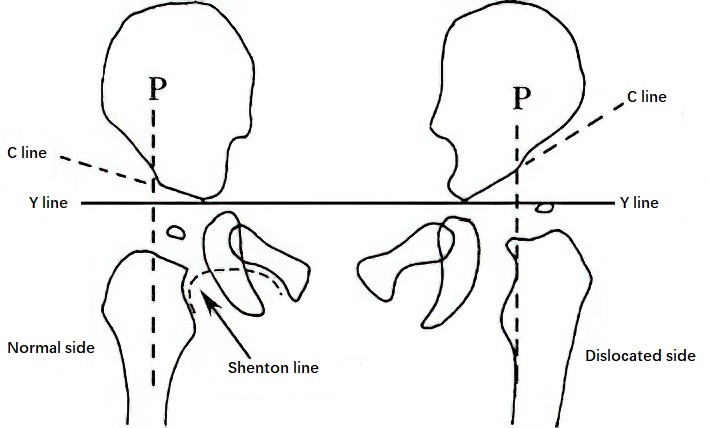

Several reference lines drawn on an anteroposterior pelvic X-ray can assist in diagnosis:

Acetabular Index

The developmental status of the hip joint is often assessed using the acetabular index (also called the acetabular angle). A line, referred to as the Y-line, is extended from the central points of bilateral acetabular cartilages (or Y-shaped cartilage). Another line, called the C-line, connects the central point of the Y-shaped cartilage to the superolateral edge of the acetabulum. The angle formed by the C-line and the Y-line is the acetabular index/angle. The normal range for newborns is 30°–40°, 23°–28° at 1 year, and 20°–25° at 3 years. Values exceeding this range indicate acetabular dysplasia. This angle gradually decreases as the child begins walking and stabilizes at approximately 15° by age 12.

Perkin Quadrants

After the ossification of the femoral head epiphysis nucleus, Perkin quadrants can be used. The Y-line connects the centers of both acetabular cartilages, and a perpendicular line (P-line) is drawn from the superolateral acetabular edge to the Y-line, dividing the hip joint into four quadrants. A normal femoral head epiphysis is located in the inferomedial quadrant. Its presence in the inferolateral quadrant indicates subluxation, while its presence in the superolateral quadrant indicates complete dislocation.

Figure 6 Diagram of Perkin quadrants, acetabular index, and Shenton line

Shenton Line

This is a continuous curved line formed by the medial edge of the femoral neck and the upper edge of the obturator foramen. Normally, it forms a smooth parabola, but this line is interrupted in cases of dislocation.

CT and MRI Examinations

In recent years, CT has been used to measure the femoral neck anteversion angle due to its simplicity and accuracy. CT with three-dimensional reconstruction allows observation of the femoral neck and acetabulum from any angle, providing precise information on the femoral neck axis, anteversion angle, and other developmental aspects. MRI reveals the relationship between surrounding soft tissues, the femoral head, and the acetabulum, offering valuable insights for treatment planning and evaluating therapeutic outcomes.

Treatment

The prognosis depends heavily on early diagnosis and treatment, with earlier intervention leading to better outcomes.

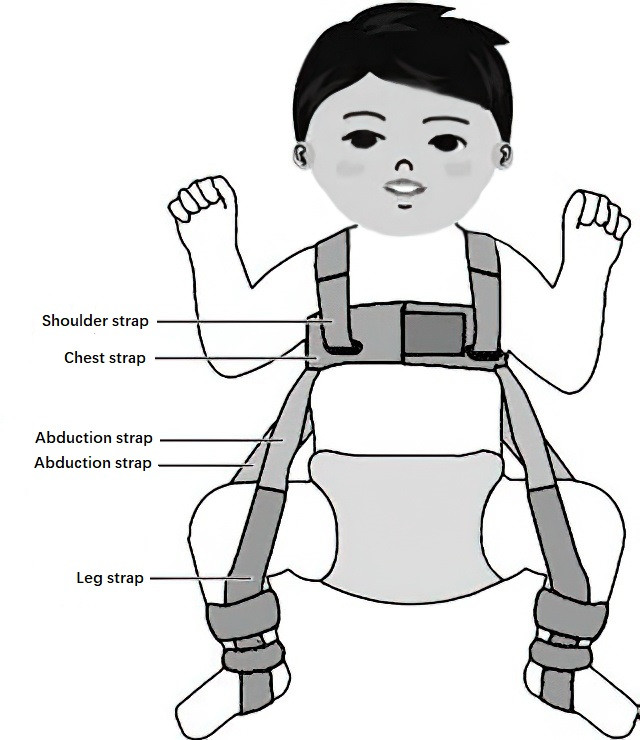

Neonatal Period (0–6 Months)

This age range represents the best opportunity for treatment. The goal of treatment is to stabilize the hip joint. During this stage, reduction surgery is not required. Fixation methods that maintain the hip joint in an abducted and flexed position can achieve favorable outcomes. The Pavlik harness is the first choice, maintaining the hip in 100°–110° flexion and 20°–50° abduction, worn continuously for 24 hours. Regular follow-ups determine its efficacy, and after 2–4 months of use, transition to an abduction brace is recommended until the acetabular index decreases to below 25°. Other methods, such as pantyhose braces or swaddling braces in abduction position, are utilized, maintaining correction for over 4 months.

Figure 7 Pavlik harness for the treatment of developmental dislocation of the hip.

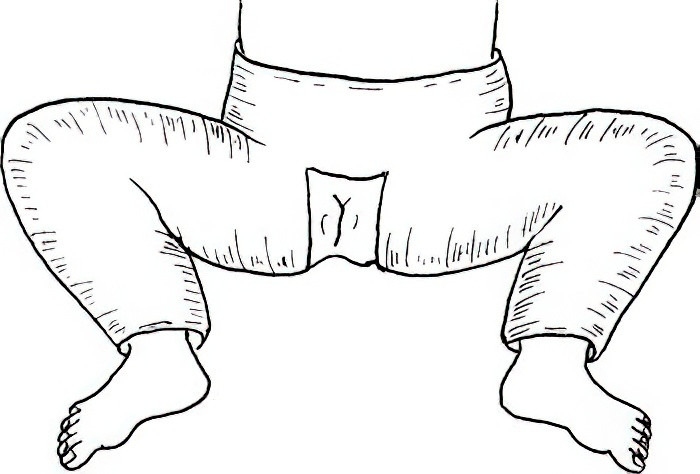

Infancy (6 Months–1.5 Years)

During this period, increased mobility and body weight exacerbate dislocation of the femoral head, reducing the likelihood of spontaneous reduction. The success rate of Pavlik harness treatment significantly decreases, necessitating closed or open reduction. Closed reduction under anesthesia is preferred, with the hip joint fixed in 95° flexion and 40°–45° abduction using casts or braces. This "human position," advocated by Salter, provides the most stable joint alignment with the lowest risk of avascular necrosis. Adductor longus tenotomy, and in some cases iliopsoas tenotomy, is performed before reduction to alleviate femoral head pressure and reduce the risk of avascular necrosis. After 3 months, the fixation is replaced with abduction braces or plaster casts for an additional 3–6 months.

Figure 8 Application of the "human position" plaster cast.

Toddler Period (1.5–3 Years)

By this age, children are able to walk independently, and secondary pathological changes become more severe. Muscle groups spanning from the femur to the pelvis become significantly shortened, complicating manual reduction or reducing its efficacy. Many scholars recommend open reduction as the best treatment option after 1.5 years. The femoral head is repositioned into the true acetabulum, accompanied by pelvic or femoral osteotomy to reconstruct a normal head-acetabulum relationship.

Childhood and Beyond (3+ Years)

Older children experience progressive dislocation, with adaptive soft tissue contractures around the hip joint and structural changes to the acetabulum and femoral head. Surgical intervention is required, typically involving open reduction, pelvic osteotomy, and proximal femoral osteotomy. These procedures aim to reduce pressure between the femoral head and acetabulum, correct excessive neck anteversion and neck-shaft angles, and enhance femoral head coverage by the acetabulum. For children over 8 years old, the femoral head may no longer align with the acetabular level, leading to poor post-surgical joint function. In such cases, palliative or salvage surgeries are considered, though their use remains controversial.

Common surgical techniques include:

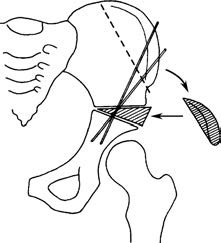

- Salter Pelvic Osteotomy: Suitable for children under 6 years old with an acetabular index <45° and anterior acetabular deficiency.

- Pemberton Periacetabular Osteotomy: Used for children with an open Y-shaped cartilage epiphysis and a larger acetabular index.

- Steel Triple Pelvic Osteotomy: This involves cutting the ischium, pubis, and ilium above the acetabulum to realign the acetabular orientation. It is primarily employed in older children with poor acetabular development not amenable to Salter osteotomy.

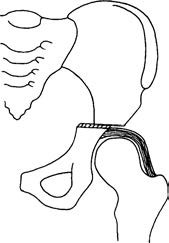

- Chiari Medial Displacement Osteotomy: Appropriate for older children with an acetabular index >45°. However, it may narrow the birth canal in females, and the newly created coverage may lack cartilage.

- Total Hip Arthroplasty: Performed for patients with secondary osteoarthritis or femoral head necrosis due to developmental dislocation of the hip. When pain cannot be alleviated by previous pelvic or femoral osteotomies, total hip replacement at an appropriate age can correct limb shortening, significantly improve hip joint function, and relieve pain.

Figure 9 Salter osteotomy

Figure 10 Chiari medial displacement osteotomy