Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) refers to a condition characterized by unilateral fibrotic contraction of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, resulting in abnormal tilting of the head and neck towards the affected side. It is one of the most common congenital musculoskeletal disorders in newborns and infants.

Etiology

The exact cause remains unclear and is still debated. The prevailing theory attributes the condition to birth trauma or malposition in utero, leading to localized ischemia. Bleeding within one sternocleidomastoid muscle caused by birth trauma may lead to hematoma formation, fibrosis, and subsequent contracture. Abnormal fetal positioning in utero could exert excessive pressure on one side of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, causing localized ischemia and resulting in contracture. Some researchers believe the fibrosis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle originates in utero due to congenital or genetic factors. Other hypotheses include intrauterine or external infections, as well as arterial or venous embolism.

Clinical Manifestations

A firm, oval, or round immobile mass in one sternocleidomastoid muscle is typically noted shortly after birth. The surface of the mass is not erythematous, exhibits normal temperature, and is non-tender. The head tilts towards the affected side, while the chin rotates towards the unaffected side, with both active and passive movements of the chin towards the affected side (or tilting of the head towards the unaffected side) becoming restricted to varying degrees. The mass gradually diminishes in size or disappears within approximately six months, leaving behind a fibrotic, cord-like contracture. In some cases, the mass does not fully resolve. Contracture of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may develop directly without a preceding mass. Continued progression can cause secondary deformities, such as shortened and flattened facial features on the affected side, elongated and rounded features on the unaffected side, eyes and ears misaligned on different planes, and, in severe cases, cervical scoliosis.

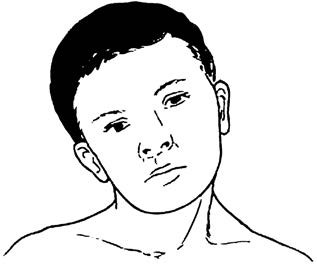

Figure 1 Illustration of congenital muscular torticollis

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be established based on clinical findings, including cord-like contracture of the affected sternocleidomastoid muscle and head and facial tilting. Although the diagnosis of congenital muscular torticollis is straightforward, distinguishing it from other causes of torticollis is necessary.

Osseous Torticollis

Congenital cervical spine abnormalities such as atlantoaxial subluxation, hemivertebrae, or odontoid dysplasia can cause torticollis of varying degrees. The sternocleidomastoid muscle remains unaffected. Diagnosis is confirmed through X-ray imaging.

Infectious Torticollis

Torticollis resulting from infections such as pharyngitis, tonsillitis, or suppurative/tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis occurs due to inflammation-induced irritation, leading to congestion and edema of local soft tissues or increased ligamentous laxity of the cervical spine. This can result in rotational displacement of the atlantoaxial joint, causing torticollis. The sternocleidomastoid muscle shows no contracture in such cases.

Visual Torticollis

Visual impairments such as refractive errors, oculomotor nerve palsy, or ptosis may lead to a compensatory head-tilting posture while viewing objects. The sternocleidomastoid muscle remains unaffected, and no restriction of neck movement occurs.

Treatment

Early detection and intervention are critical to achieving good outcomes and preventing secondary deformities of the face and cervical spine. Late-stage torticollis can be corrected surgically, although any associated deformities of the face or cervical spine may be more challenging to address.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Non-surgical management aims to facilitate the resolution of localized masses and prevent sternocleidomastoid muscle contracture. It is most effective in infants under one year of age. Treatment involves local heat application, gentle massage, manual correction, and external fixation using an orthopedic hat. Daily sessions of gentle massage and thermal therapy, combined with moderate traction of the head towards the unaffected side, are typically performed several times a day, with each session lasting 10–15 repetitions. During sleep, a sandbag can be used to stabilize the head in a corrected position. Consistent and persistent treatment often yields satisfactory results.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is indicated for patients older than one year. The optimal age for surgery is between 1 and 4 years. The most common surgical procedure is sternocleidomastoid tenotomy. In milder cases, sectioning of only the clavicular or sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may suffice, followed by the use of a cervical collar to maintain slight overcorrection. In severe cases or for children over four years of age, simultaneous sectioning and release at both ends of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be performed. Postoperatively, head, and cervical braces are used to immobilize the area for 4–6 weeks, maintaining the head and neck in an over-corrected position to prevent recurrence.

For individuals older than 12 years, facial asymmetry and cervical deformities may be difficult to fully correct surgically. However, surgical methods can still achieve some improvement in these patients. During surgery, care is taken to avoid injury to the facial nerve, accessory nerve, and subclavian vessels.