Renal angiomyolipoma (AML), also known as renal hamartoma, is the most common benign renal tumor. It is typically composed of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue, and most commonly occurs in middle-aged women, with an incidence age range of 30 to 60 years. Renal angiomyolipoma may occur as an isolated condition or as a manifestation of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by germline mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 gene that result in protein dysfunction. It can affect multiple organs and systems, with renal manifestations often involving multiple angiomyolipomas.

Pathology

Renal angiomyolipoma can originate from both the renal cortex and medulla. Tumor size varies, and its cut surface appears grayish-yellow or mixed yellow, with occasional hemorrhagic areas. The tumor may grow outward from the kidney or into the collecting system. Although it lacks a complete capsule, it is well demarcated. The tumor is composed of varying proportions of blood vessels, smooth muscle, and mature adipose tissue, with possible inclusion of fibrous tissue. It is rich in blood vessels, and the vessel walls are irregular in thickness, lack elasticity, and exhibit tortuosity, sometimes forming aneurysms. Under external forces, these vessels are prone to rupture, leading to hemorrhage.

Clinical Manifestations

Most cases are incidentally detected during ultrasound or CT imaging conducted for physical examinations or other reasons. Tumor hemorrhage may present with sudden localized pain, while rupture of large tumors may cause acute flank or abdominal pain, hypovolemic shock, hematuria, and an abdominal mass.

Tuberous sclerosis complex-associated angiomyolipoma (TSC-AML) may present with additional features, such as facial angiofibromas distributed in a butterfly pattern, seizures, and intellectual disability.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis primarily relies on imaging studies, including ultrasound, CT, or MRI.

Ultrasound

Fat content within angiomyolipoma creates a significant sound impedance difference with surrounding tissues, often appearing as hyperechoic. In contrast, renal cell carcinoma, lacking fat tissue, typically appears hypoechoic on ultrasound.

CT

Angiomyolipomas are seen as round or lobulated renal masses, unilateral or bilateral, containing patchy or multifocal areas of extremely low-density fat (CT attenuation < -20 HU). Tumor margins are generally well-defined. Characteristic fat density helps distinguish angiomyolipoma from renal cell carcinoma. Post-contrast imaging shows varying degrees of enhancement (CT attenuation increases by approximately 20–30 HU), although the enhancement is less pronounced compared to normal renal parenchyma.

Figure 1 Non-contrast enhanced CT of the kidney

A tumor is seen in the mid-region of the right kidney, containing extremely hypodense fat areas.

MRI

Fat content within angiomyolipoma displays intermediate to high signal intensity on T1-weighted (T1WI) and T2-weighted (T2`WI) imaging. On fat-suppressed T2WI, the signal is significantly reduced or appears as a low signal, which is a distinguishing feature from renal cell carcinoma.

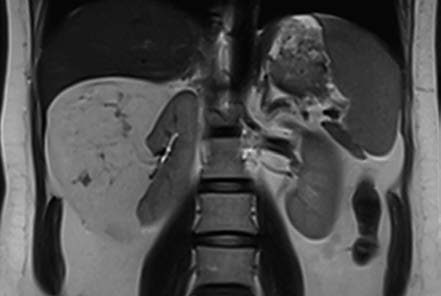

Figure 2 MRI of the kidney

A high-signal intensity tumor is visible in the mid-lower pole of the right kidney on T2WI.

Angiomyolipomas rich in fat are readily diagnosed due to their characteristic imaging findings. However, fat-poor angiomyolipomas may mimic renal cell carcinoma on ultrasound, CT, or MRI, leading to misdiagnosis.

Renal Angiography

Vascular changes within the tumor, such as irregular vessel wall thickness, lack of elasticity, and tortuosity with aneurysmal changes, can be observed. Approximately 50% of angiomyolipoma cases show aneurysmal dilation on angiography.

TSC-AML is often accompanied by characteristic extrarenal manifestations, and genetic testing can aid in diagnosis.

Treatment

Treatment approaches include the following:

Observation

For tumors smaller than 4 cm in diameter, close monitoring of the tumor's progression every 6–12 months is recommended.

Surgical Treatment

Rapid tumor growth, a diameter of ≥4 cm, or an increased risk of rupture and hemorrhage warrant consideration of partial nephrectomy. For cases of tumor rupture with hemorrhage where renal artery embolization is not feasible, surgery is performed. Surgical intervention aims to achieve hemostasis and tumor resection while preserving as much normal renal tissue as possible.

Interventional Therapy

For ruptured angiomyolipomas with significant hemorrhage that cannot be managed conservatively, selective renal arterial embolization is utilized. In patients with tuberous sclerosis complex, bilateral lesions, or impaired renal function, selective embolization is also an option.