Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), commonly referred to as kidney cancer, accounts for 3%–5% of all adult malignancies and 85% of malignant kidney tumors. The etiology of RCC remains unclear, although it has been associated with factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, and genetic mutations (e.g., mutations or deletion of the VHL tumor suppressor gene).

Pathology and Clinical Staging

Most renal cancers are solitary, with bilateral sequential or simultaneous occurrence observed in about 2% of cases. Tumors are generally spherical solid masses of varying sizes, often surrounded by a pseudocapsule. On cross-section, the tumors are predominantly yellow, yellow-brown, or brown, and approximately 20% of cases exhibit cystic changes and calcifications. RCC originates from the epithelial cells of the renal tubules, with pathological subtypes including clear cell carcinoma, papillary renal cell carcinoma, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, collecting duct carcinoma, renal medullary carcinoma, MiT family translocation renal cell carcinoma, and unclassified RCC. Among these, clear cell carcinoma comprises 70%–80% of cases. Its characteristic appearance under the microscope is due to the cytoplasm's high content of glycogen, cholesterol esters, and phospholipids, which are dissolved during tissue processing, leaving the cytoplasm with a transparent appearance. RCC is most commonly staged using the TNM staging system.

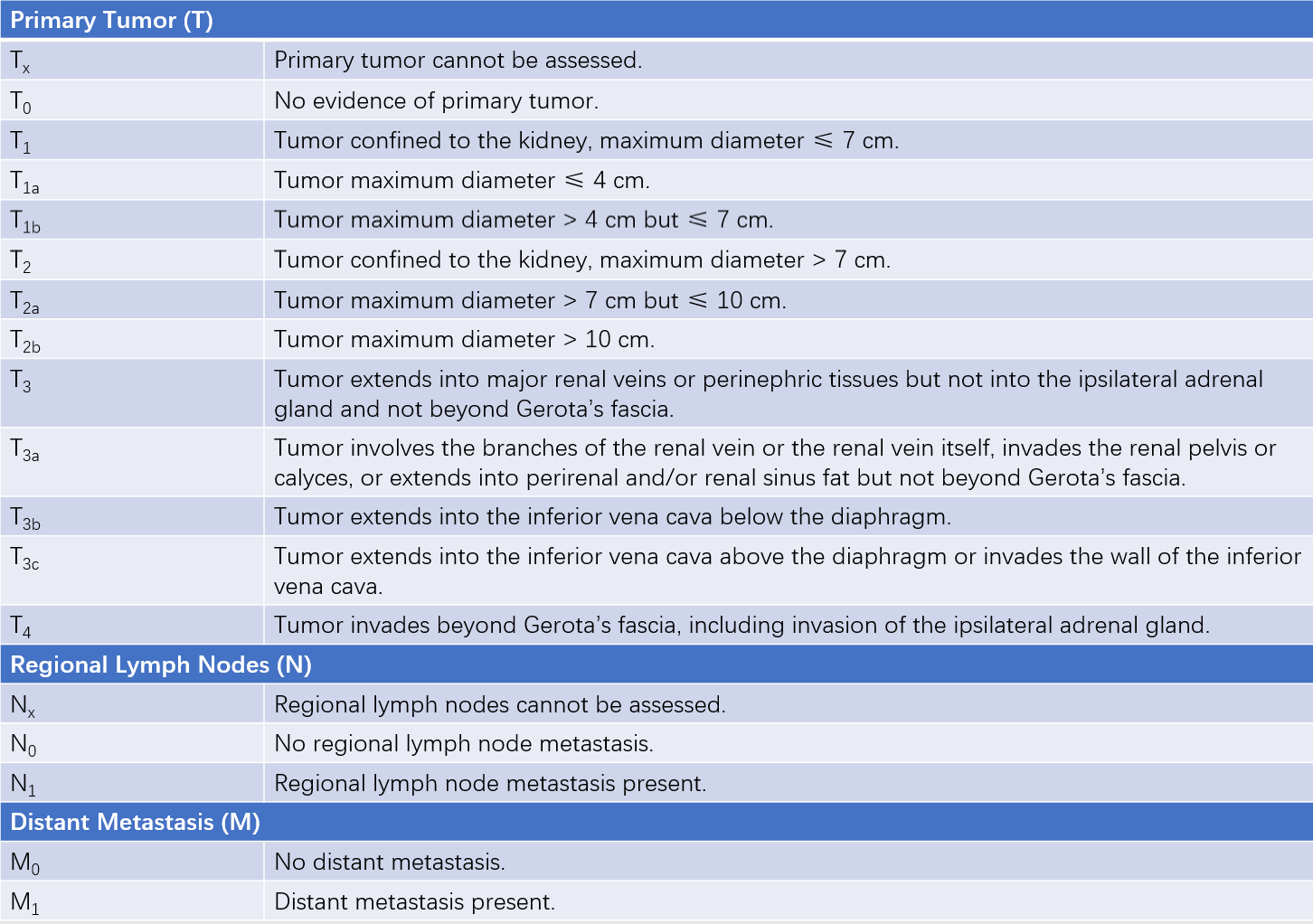

Table 1 TNM classification of renal cell carcinoma (AJCC, 2017)

Clinical Presentation

RCC is most frequently diagnosed between the ages of 50 and 70, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:2. Early stages of RCC are often asymptomatic, with around 60% of cases detected incidentally during health check-ups or examinations for other conditions. Common clinical manifestations include:

Hematuria, Pain, and Mass

Hematuria is the most common symptom, presenting as intermittent, painless, gross hematuria, indicating that the tumor has invaded the renal calices or renal pelvis. Pain typically manifests as dull or aching pain in the lumbar region, often due to tumor growth stretching the renal capsule or invading the psoas major muscle and adjacent organs. Blood clots resulting from hemorrhage may obstruct the ureter and lead to renal colic. In cases of large tumors, a palpable mass may be felt in the abdomen or lumbar region. Tumor involvement of the left renal vein or venous tumor thrombus formation may cause ipsilateral varicocele. Tumor thrombi may also enter the inferior vena cava, forming caval tumor thrombi.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

These syndromes occur due to the release of cytokines or hormones by the renal tumor and are unrelated to direct tumor invasion, distant metastasis, infection, or malnutrition. They occur in 10%–20% of RCC patients and may manifest as fever, hypertension, hematologic abnormalities (polycythemia, thrombocytosis), and metabolic changes (hypercalcemia, hyperglycemia). Hypertension is possibly caused by renin production by the tumor, polycythemia by erythropoietin secretion, and hypercalcemia by tumor secretion of parathyroid hormone-like substances.

Symptoms of Metastases

The most common metastatic sites of RCC are the lungs, bones, liver, and adrenal glands. Lung metastases may present with coughing or hemoptysis, while bone metastases may cause bone pain and associated symptoms.

Diagnosis

Imaging plays a central role in the diagnosis of RCC.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is non-invasive, affordable, and suitable for routine screening of RCC. Typical RCC appears as a heterogeneous, solid mass with hypoechoic or isoechoic signals. Partially cystic RCC may appear as an anechoic cystic mass, and calcifications may present as localized hyperechoic areas.

CT

CT shows a high diagnostic accuracy for RCC and provides detailed information about tumor location, size, and involvement of adjacent structures. RCC typically appears as a inhomogeneous, rounded mass within the renal parenchyma. On unenhanced CT scans, the tumor’s density is usually slightly lower or similar to that of the renal parenchyma, though occasionally higher. Contrast-enhanced CT often reveals significant tumor enhancement.

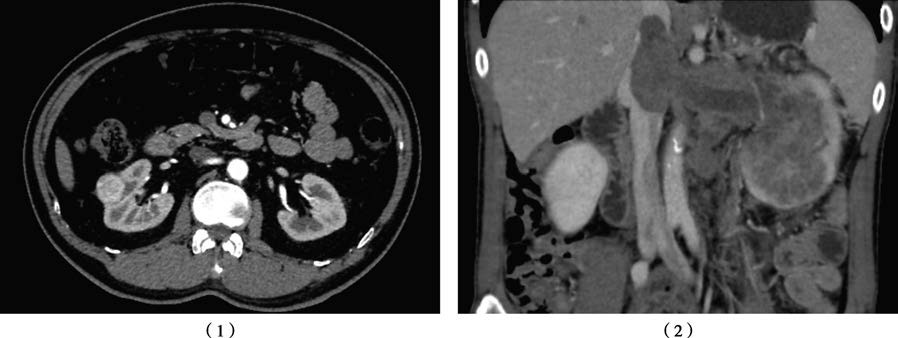

Figure 1 Contrast-enhanced CT of the kidney

1, Right renal carcinoma, primary tumor staged as T1a.

2, Left renal carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus, primary tumor staged as T3b.

MRI

The diagnostic accuracy of MRI for RCC is comparable to that of CT. However, MRI is superior to CT in evaluating local invasion of adjacent structures and detecting tumor thrombi in the renal vein or inferior vena cava. Most RCC lesions appear as iso- or hypointense signals on T1-weighted images (T1WI) and as inhomogeneous hyperintense signals on T2-weighted images (T2WI).

Treatment

The treatment plan should be developed based on the clinical stage of the disease. Advances in targeted and immunotherapy have shifted the treatment paradigm for renal cell carcinoma (RCC) from solely surgical intervention to a comprehensive approach.

Surgical Treatment

The primary surgical options include partial nephrectomy (PN) and radical nephrectomy (RN). Partial nephrectomy is mainly suitable for T1-stage RCC. For certain T2-stage RCC cases, as well as RCC occurring in anatomically or functionally solitary kidneys, RCC with concurrent chronic kidney disease, familial RCC, or bilateral RCC, partial nephrectomy may be considered as long as tumor control is achieved. Radical nephrectomy is primarily employed for T1-stage RCC not amenable to partial nephrectomy, as well as for T2 to T4-stage RCC. The scope of radical nephrectomy includes the kidney, perirenal fat, and upper ureter. Lymph node dissection is generally not routinely performed during RN unless lymph node enlargement is observed intraoperatively or lymph node metastasis is suspected based on preoperative imaging. For tumors located in the upper pole or invading the ipsilateral adrenal gland, adrenalectomy on the affected side is recommended. Tumors involving the perirenal fascia should also be resected. If tumor thrombi are present within the renal vein or inferior vena cava, tumor thrombectomy is performed.

Surgical techniques for RCC have evolved from open surgery to minimally invasive approaches. Laparoscopic and robot-assisted laparoscopic surgeries have become mainstream procedures, while more minimally invasive techniques, such as radio-frequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), are being applied experimentally in cases of small renal tumors not suitable for partial nephrectomy.

Systemic Therapy

RCC is generally resistant to both radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Recent studies have revealed that for advanced RCC, the combination of molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy significantly improves tumor control rates and extends overall survival. Common molecular targeted drugs include tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sorafenib and sunitinib, as well as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors such as everolimus and sirolimus. Immunotherapy drugs include immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-PD-1 antibodies, anti-PD-L1 antibodies, and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies.

Prognosis

The prognosis of RCC is closely related to clinical staging and pathological type. The five-year overall survival rate for localized RCC is approximately 91%–96%, for locally advanced RCC approximately 69%–74%, and for metastatic RCC approximately 12%–17%.