Pathology

Mycobacterium tuberculosis spreads to the kidneys via hematogenous dissemination, primarily affecting the glomerular capillary network in the renal cortex and forming multiple tiny tuberculous foci. These regions are rich in blood circulation and have strong reparative capacity. If the individual has a robust immune system, a small bacterial load, or low bacterial virulence, these early microscopic tuberculous lesions may completely heal on their own, often without presenting clinical symptoms, a condition referred to as latent renal tuberculosis. In such cases, Mycobacterium tuberculosis may still be detected in the urine. When immunity is compromised, bacterial load is high, or the bacteria exhibit strong virulence, the foci in the renal cortex fail to heal and gradually enlarge. The bacteria spread through the renal tubules to the loop of Henle in the renal medulla, where the reduced blood flow and poor circulation facilitate the development of renal medullary tuberculosis. As the disease progresses in the medulla, the lesions may penetrate the renal papilla, spreading to the renal calyces and pelvis to cause tuberculous pyelonephritis. Clinical symptoms and imaging abnormalities manifest at this stage, referred to as clinical renal tuberculosis. The condition is predominantly unilateral.

The early lesions of renal tuberculosis consist of inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal cortex, resulting in multiple tuberculous nodules. The progression of the disease leads to expansion of the lesions, infiltration into the renal medulla, and the inability of the lesions to heal naturally. Tuberculous nodules may coalesce, forming caseous abscesses that erode through the renal papilla into the calyces and pelvis, producing cavitary ulcers. These lesions can continue to enlarge and spread, eventually involving the entire kidney. Fibrosis at the neck of the renal calyces or at the renal pelvis outlet may cause stenosis, leading to localized abscesses or tuberculous pyonephrosis. Tuberculous calcification is a common pathological feature, appearing as either scattered calcified plaques or diffuse calcification of the entire kidney. In rare cases, widespread renal calcification contains caseous material, resulting in complete loss of renal function. Obstruction of the ureter often prevents urine containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis from entering the bladder. Consequently, secondary bladder tuberculosis may gradually improve or resolve, with irritative bladder symptoms subsiding and urine tests returning to normal. This phenomenon is termed "autonephrectomy." However, significant amounts of viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis remain in the lesions, serving as reservoirs for potential recurrence. A lack of pronounced symptoms should not lead to neglect of the condition.

Ureteral tuberculosis involves tuberculous nodules, ulcers, granulomas, and fibrosis in the mucosa and submucosa of the ureter. The lesions are often multifocal. During the healing process, fibrosis causes thickening and stiffening of the ureteral wall, resulting in segmental ureteral stricture. This obstruction disrupts urinary outflow, leading to hydronephrosis, further accelerating renal tuberculous damage, and eventually causing complete loss of kidney function, such as in tuberculous pyonephrosis. Atypical renal tuberculosis has been increasingly observed, with nonspecific clinical manifestations. Laboratory and imaging studies play a valuable role in diagnosing such cases, which are categorized as atypical renal tuberculosis. Ureteral strictures are most frequently observed at the ureterovesical junction.

Bladder tuberculosis begins with mucosal congestion and edema, accompanied by scattered tuberculous nodules. These lesions typically originate around the affected ureteral orifice and gradually spread to other areas of the bladder. Tuberculous nodules may merge to form ulcers or granulomas and, in some cases, may extend into the muscular layer. Tuberculous ulcers are relatively uncommon; as the lesions heal, extensive fibrosis and scarring of the bladder wall occur, leading to a loss of bladder distensibility. Bladder capacity may significantly decrease to less than 50 ml, a condition known as a contracted bladder. Tuberculous bladder lesions and contracted bladder may cause narrowing or incomplete closure of the healthy ureteral orifice, forming a gaping ureteral orifice. Increased intravesical pressure may result in obstructed outflow of urine from the renal pelvis or vesicoureteral reflux, causing hydronephrosis in the contralateral kidney. Contracted bladder and contralateral hydronephrosis are common late-stage complications of renal tuberculosis. In rare cases, deep invasion of bladder wall tuberculosis may result in fistula formation with adjacent organs, such as tuberculous vesicovaginal or vesicorectal fistulas.

Urethral tuberculosis primarily affects males and is often a result of cavitation and destruction of the posterior urethra due to tuberculous prostate or seminal vesicle involvement. In rare cases, it may stem from the spread of bladder tuberculosis. Pathological changes include tuberculous ulcers and fibrosis, which cause urethral stricture, resulting in difficulty urinating and exacerbating renal impairment.

Clinical Manifestations

Renal tuberculosis predominantly occurs in young and middle-aged adults between the ages of 20 and 40, with a higher incidence in males compared to females. It is relatively uncommon in children and the elderly. In children, cases are mostly observed above the age of 10, while occurrences in infants and young children are exceedingly rare. Approximately 90% of cases are unilateral.

The symptoms of renal tuberculosis depend on the extent of renal involvement and the severity of secondary tuberculous lesions in the ureters and bladder. In the early stages, renal tuberculosis is often asymptomatic, with no notable imaging abnormalities. Urinalysis may reveal a small number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and protein, with acidic urine potentially containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis. As the disease progresses, the following characteristic clinical manifestations may develop:

Increased Frequency, Urgency, and Painful Urination

These are among the hallmark symptoms of renal tuberculosis. Increased urinary frequency is often one of the earliest signs and frequently serves as the reason for seeking medical attention. It progressively worsens and does not respond to conventional antibiotic treatment. Initially, the symptoms are caused by purulent urine containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis irritating the bladder mucosa. Over time, as the tuberculosis lesion invades the bladder wall, leading to tuberculous cystitis and ulcers, urinary frequency intensifies and is accompanied by urgency and dysuria. In the advanced stages, bladder contraction and significant reduction in bladder capacity exacerbate urinary frequency, with patients voiding several dozen times a day or even experiencing urinary incontinence.

Hematuria

Hematuria is an important symptom of renal tuberculosis, often presenting as terminal hematuria. This typically results from tuberculous cystitis and ulceration, with bleeding occurring during bladder contraction at the end of urination. In rare cases where the tuberculous lesion invades a blood vessel, gross hematuria throughout the urinary stream may occur. Hematuria in renal tuberculosis often emerges after symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria have already appeared; however, in some cases, hematuria may be the initial presenting symptom.

Pyuria

Pyuria is a common symptom in renal tuberculosis. Patients exhibit varying degrees of pyuria, with severe cases producing urine that resembles rice water and may contain caseous debris or flocculent material. Microscopy reveals abundant pus cells in such cases.

Lower Back Pain and Palpable Mass

Only a small subset of cases experiences significant symptoms such as pain or a palpable mass. These occur when extensive renal destruction, obstruction, tuberculous pyonephrosis, secondary perirenal infection, or ureteral blockage by blood clots or caseous material develops. Patients may report dull or colicky lower back pain. In cases of large renal abscesses or significant contralateral hydronephrosis, a palpable mass may be present in the lumbar region.

Male Genital Tuberculosis

Approximately 50% to 70% of male patients with renal tuberculosis also exhibit tuberculosis of the genital system. Although the primary lesions usually begin in the prostate or seminal vesicles, epididymal tuberculosis is the most prominent clinical manifestation. In such cases, the epididymis may present as irregular, hard nodules. Tuberculous involvement of the vas deferens results in thickened, hardened, beaded changes characteristic of this disease.

Systemic Symptoms

Systemic symptoms are often mild or absent in patients with renal tuberculosis. In advanced disease stages or cases of coexisting active tuberculosis in other organs, patients may exhibit typical tuberculosis-related systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, anemia, weakness, and loss of appetite. Severe bilateral renal tuberculosis or unilateral hydronephrosis due to contralateral renal tuberculosis can lead to symptoms of chronic renal failure, including anemia, edema, nausea, vomiting, oliguria, and in extreme cases, sudden anuria.

Diagnosis

Renal tuberculosis is one of the causes of chronic cystitis. For cases of chronic cystitis without an obvious cause, where symptoms persist and progressively worsen, accompanied by terminal hematuria, and ineffective treatment with antibiotics, the possibility of tuberculosis of the urinary system should be considered. This is particularly relevant for young and middle-aged men who experience recurrent painless urinary frequency or unexplained hematuria, or those with epididymal induration or a chronic fistulous tract in the scrotum. The following examinations assist in the diagnostic process:

Urinalysis

The urine is typically acidic and may show positive proteinuria, along with increased red and white blood cells. Acid-fast staining of urinary sediment may reveal acid-fast bacilli in some cases, though the majority of cases yield negative results. The first morning void provides the highest detection rate, and testing should ideally be performed at least three consecutive times. Detection of acid-fast bacilli should not be the sole basis for diagnosing renal tuberculosis, as other acid-fast bacteria, such as smegma bacilli or Bacillus subtilis, could be mistaken for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Culturing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis is more reliable, though it requires a longer time (4–8 weeks). The culture has a detection rate of up to 90%, making it a decisive method for confirming renal tuberculosis.

Imaging Diagnostics

Imaging, including ultrasound, plain X-ray films, CT, and MRI, plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis, assessing the severity of the lesions, and determining treatment strategies.

X-ray Plain Films

Kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) X-rays may reveal focal or speckled calcifications in the affected kidney or widespread calcification throughout the kidney. Intravenous urography (IVU) provides essential information on renal function on each side, the extent of the lesions, and their distribution, which is indispensable for choosing an appropriate treatment plan. Early stages may show irregular, worm-eaten-like edges of the renal calyces. Over time, calyces lose their cup-shaped outline, appear irregularly enlarged, or become deformed. Fibrotic narrowing or complete occlusion of the calyceal neck may lead to incomplete or absent filling of the cavities on imaging. In cases of extensive destruction and complete functional loss of the kidney, the affected kidney appears as "nonfunctional" and fails to display typical tuberculous lesions. If Mycobacterium tuberculosis is detected in urine and IVU reveals one kidney as normal and the other as "nonfunctional" despite lacking typical tuberculous imaging changes, renal tuberculosis can still be diagnosed based on clinical findings.

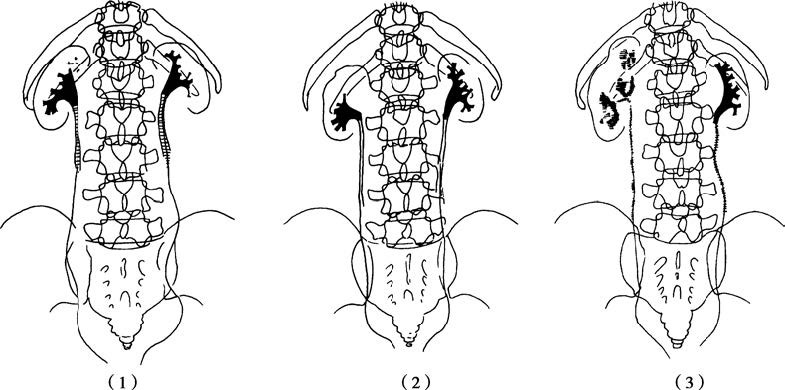

Figure 1 Illustration of renal tuberculosis (retrograde pyelography)

(1) Destruction of the upper right renal calyx

(2) Non-filling of the upper right renal calyx

(3) Severe destruction of the right kidney and ureter

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is a straightforward method that can preliminarily identify lesion locations in middle and late stages of the disease. It often shows disorganized kidney structures, with calcifications appearing as hyperechoic areas. Ultrasound is also useful in detecting contralateral hydronephrosis or bladder contraction.

CT and MRI

CT imaging clearly visualizes expanded renal calyces and pelvis, cortical cavitations, and areas of calcification in middle-to-late-stage renal tuberculosis, presenting a patchwork-like appearance. CT urography (CTU) can capture lesions spanning the entire ureter, including thickened walls and increased external diameter. MRI water imaging provides specific advantages in diagnosing contralateral hydronephrosis associated with renal tuberculosis. When bilateral renal tuberculosis or contralateral hydronephrosis compromises the visualization on intravenous urography, CT and MRI contribute to establishing a definitive diagnosis.

Cystoscopy

On cystoscopic examination, bladder mucosal changes may include congestion, edema, pale yellow tuberculous nodules, tuberculous ulcers, granulomas, and scarring, most prominently in the bladder trigone and around the affected ureteral orifice. Tuberculous granulomas may resemble tumors and require biopsy for definitive diagnosis. The affected ureteral orifice can appear "cave-like," occasionally discharging cloudy urine. Cystoscopy is contraindicated in cases of bladder contraction with a capacity below 50 ml or acute cystitis.

Delayed diagnosis of renal tuberculosis is often due to two common issues. One occurs when management focuses solely on cystitis, and the lack of a satisfactory response to conventional antibiotics leads to missed evaluations for underlying causes. The other involves diagnosing male genital tuberculosis, especially epididymal tuberculosis, without recognizing its frequent coexistence with renal tuberculosis. This oversight leads to missed urine testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, as well as missed imaging evaluations like intravenous urography, CT, CTU, or MRU.

Differential Diagnosis

Renal tuberculosis must primarily be distinguished from nonspecific cystitis and other conditions causing hematuria within the urinary system. Tuberculous cystitis caused by renal tuberculosis typically begins with urinary frequency, with bladder irritative symptoms that persist long-term and worsen progressively without responding to conventional antibiotics. Nonspecific cystitis, mainly caused by Escherichia coli infection, is more common in women, has an acute onset, and presents with prominent frequency, urgency, and dysuria from the beginning. Symptoms resolve quickly with antibiotics, resulting in a shorter disease course, although relapses are frequent.

Hematuria associated with renal tuberculosis often appears after a period of bladder irritative symptoms and is usually terminal. This differs from hematuria caused by other urinary system conditions. Hematuria from urinary tract tumors is often initial and painless, presenting as gross hematuria throughout the urinary stream. Hematuria from renal or ureteral calculi is typically accompanied by renal colic. Hematuria caused by bladder calculi may be associated with sudden interruption of the urinary stream and severe urethral pain during urination. Nonspecific cystitis-associated hematuria primarily occurs in the acute stage and coincides with bladder irritative symptoms. However, the key distinguishing feature of renal tuberculosis is the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the urine, either through direct acid-fast staining or positive cultures, which are absent in other conditions.

Treatment

Renal tuberculosis is part of a systemic tuberculosis infection, and its management requires attention to overall treatment, including improving nutrition, ensuring rest, and avoiding exhaustion. Treatment strategies for renal tuberculosis depend on the patient's general condition and the extent of renal involvement, with options including pharmacological therapy and surgical intervention. The principles of drug therapy include early initiation, appropriate dosage, combination regimens, regular administration, and completing the full course of treatment.

Pharmacological Therapy

Pharmacological treatment is primarily suitable for early-stage renal tuberculosis, particularly cases where Mycobacterium tuberculosis is present in the urine, but imaging reveals that the renal calyces or pelvis have no significant structural changes, or only one or two calyces appear irregularly eroded. With the appropriate use of anti-tuberculosis drugs, such cases are generally curable.

Commonly used first-line bactericidal anti-tuberculosis drugs include isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin. Second-line bacteriostatic drugs, such as ethambutol, cycloserine, and ethionamide, are used when necessary. Typical pharmacological regimens involve isoniazid 300 mg/day, rifampin 600 mg/day, pyrazinamide 1.0–1.5 g/day, vitamin C 1.0 g/day, and vitamin B6 60 mg/day, all taken once daily. If bladder involvement is extensive and symptoms of bladder irritation are severe, intramuscular streptomycin 1.0 g/day may be added during the initial two months of treatment, with pyrazinamide replaced by ethambutol 1.0 g/day after two months. Since many anti-tuberculosis drugs have hepatotoxicity, concurrent hepatoprotective drugs are recommended during treatment, along with regular liver function tests. Streptomycin can affect the eighth cranial nerve, impairing hearing, and must be discontinued immediately if such effects occur.

Pharmacological therapy is most effective when at least three drugs are used in combination to minimize the risk of drug resistance during treatment. Adequate dosages and sufficiently long treatment durations are critical. Early-stage renal tuberculosis can be potentially cured with drug therapy courses lasting 6–9 months. In practice, the main cause of treatment failure is incomplete therapy. Monthly urinalysis and tests for acid-fast bacilli, along with intravenous urography when necessary, are recommended to evaluate the therapeutic response. A stable conversion to negative Mycobacterium tuberculosis findings in the urine for six consecutive months indicates effective treatment. If no recurrence occurs within five years, the patient may be considered cured. However, in cases with significant bladder tuberculosis or involvement of other organs, follow-up may need to continue for 10–20 years or longer.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention becomes necessary when pharmacological therapy fails to achieve results after 6–9 months or when the renal tuberculosis has caused significant structural destruction. Preoperative anti-tuberculosis drug treatment for at least two weeks is essential before surgical procedures.

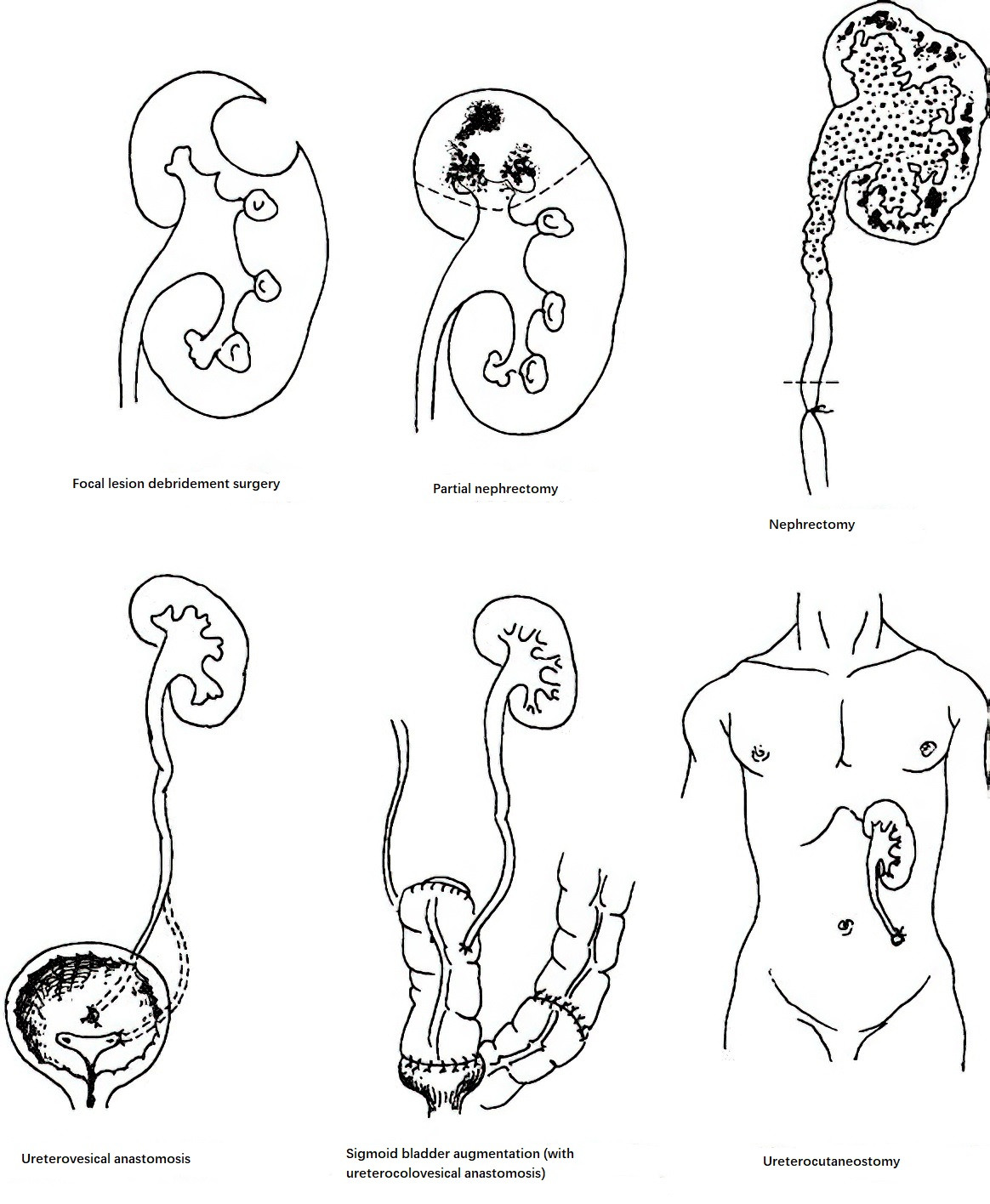

Nephrectomy

When extensive renal destruction occurs, with the contralateral kidney functioning normally, the affected kidney is removed. In cases of bilateral renal tuberculosis, where one kidney shows widespread destruction and loss of function while the other exhibits mild disease, the severely affected kidney is removed after a period of anti-tuberculosis drug therapy. For contralateral hydronephrosis associated with renal tuberculosis, drainage of the hydronephrotic kidney is performed to preserve renal function before removing the nonfunctional kidney. In recent years, laparoscopic nephrectomy for tuberculous kidneys has been widely adopted and has yielded satisfactory outcomes.

Renal Tissue-Sparing Surgery for Renal Tuberculosis

Partial nephrectomy is appropriate when lesions are localized to one pole of the kidney. Debridement surgery is an option for localized, closed tuberculous abscesses confined to the renal parenchyma and not connected to the collecting system. If no significant improvement occurs following 3–6 months of anti-tuberculosis drug therapy, these surgical options can be considered.

Surgical Management of Ureteral Strictures

Ureteral tuberculosis can cause stricture, leading to hydronephrosis. If the renal damage is mild, renal function is preserved, and the stricture is localized, end-to-end anastomosis can be performed for strictures in the upper or middle ureter. For strictures near the bladder, segmental resection with ureteroneocystostomy is performed.

Surgical Treatment for Contracted Bladder

In cases of renal tuberculosis with a contracted bladder, after 3–6 months of anti-tuberculosis therapy and complete resolution of bladder tuberculosis, patients without urethral strictures and with normal contralateral kidney function may undergo bladder augmentation with an intestinal segment. Male patients with contracted bladder often have posterior urethral strictures caused by tuberculosis of the prostate or seminal vesicles, making bladder augmentation unsuitable, especially in cases with significant hydronephrosis of the contralateral kidney. In such situations, options such as ureterocutaneostomy, ileal conduit, or nephrostomy are used to improve and preserve the remaining renal function.

Figure 2 Surgical methods for renal tuberculosis and its complications