Acute bacterial cystitis is more common in women, with 25%–30% of cases occurring in individuals aged 20–40 years. This is attributed to the female urethra being short and wide, along with the frequent presence of anatomical abnormalities at the urethral opening and significant bacterial colonization in the perineal region. Any predisposing factors for infection, such as sexual intercourse, catheterization, poor personal hygiene, or reduced individual immunity, can lead to ascending infections. This condition is rarely caused by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. In men, it is often secondary to other conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, balanitis, urethral stricture, urinary tract stones, or renal infections. It may also result from infections in adjacent organs, such as appendiceal abscesses. The most common causative organism is Escherichia coli.

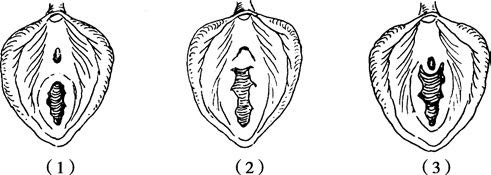

Figure 1 Normal and abnormal anatomy of the female urethral meatus

(1) Normal anatomy

(2) Hymenal hood

(3) Urethral hymenal fusion

Pathology

Superficial bladder inflammation is the most frequently observed form, with the urethral opening and bladder trigone being most affected. The lesions typically involve only the mucosa and submucosa, presenting with mucosal hyperemia, edema, petechial hemorrhages, superficial ulcers, or areas covered by purulent exudates. Microscopically, infiltration by numerous white blood cells can be seen. The inflammation may resolve on its own, leaving no residual changes after healing. However, if treatment is inadequate or there are complicating factors such as foreign bodies, residual urine, or upper urinary tract infections, the inflammation may progress to a chronic form.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset is often sudden, with symptoms primarily involving urinary irritation. In severe cases, patients may experience urination every few minutes, regardless of the time of day. A persistent sensation of incomplete bladder emptying often occurs, alongside urgency-related urinary incontinence. Patients frequently report a burning sensation in the urethra during urination and may even avoid voiding due to the discomfort. Hematuria at the end of micturition is commonly noted, which may sometimes involve total hematuria, with blood clots being occasionally passed. Systemic symptoms are typically mild, with normal body temperature or only low-grade fever. High fever is observed only when acute pyelonephritis, prostatitis, or epididymitis is present as a complication. In women, the condition may often be associated with menstruation or sexual activity.

Diagnosis

Patients typically exhibit symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, and dysuria, with tenderness over the suprapubic bladder region but without costovertebral angle pain. In men, concurrent epididymitis may be detected, with tenderness in the epididymal region. In cases of urethritis, purulent urethral discharge may be present. Additional conditions, such as prostatitis or benign prostatic hyperplasia, should also be assessed in male patients. In women, conditions such as vaginitis, urethritis, bladder prolapse, or diverticula should be considered, along with assessing for abnormalities of the hymen, urethral opening, or periurethral glands.

Urine sediment examination may reveal increased white blood cell counts and occasionally red blood cells. Urine culture, colony counting, and antibiotic sensitivity testing are recommended, leading to positive findings in typical cases. During the acute infection phase, cystoscopy and urethral dilation are contraindicated. If urethral discharge is present, bacteriological examination of smears is necessary.

Differentiation from other conditions presenting with changes in urination is required, including urethritis and vaginitis. Urethritis presents with symptoms of urinary frequency and urgency, which are generally less pronounced than in cystitis, along with dysuria but typically no chills or fever. Purulent urethral discharge is often noted. Vaginitis presents with urinary irritation accompanied by vaginal irritation, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, and is most commonly caused by pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma, herpes simplex virus, and Trichomonas.

Treatment

Antimicrobial therapy includes the use of quinolones, cephalosporins, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. For uncomplicated cystitis in women, particularly those without complications, a three-day course of sensitive antibiotics is generally preferred. For patients with symptoms lasting longer than one week or in the presence of complicating factors (e.g., urinary tract obstruction, diabetes, or immunosuppressive therapy), a treatment duration of 7–14 days may be necessary. Increased fluid intake, oral sodium bicarbonate to alkalinize urine, and reduced urinary tract irritation are often employed. Enhanced nutrition, adequate rest, and local methods such as warm compresses over the bladder area or warm sitz baths can alleviate bladder spasms.

Postmenopausal women often experience recurrent urinary tract infections due to estrogen deficiency, which decreases vaginal lactobacilli and promotes pathogenic bacteria growth. Hormone replacement therapy, aimed at maintaining a normal vaginal environment, increasing lactobacilli, and eliminating pathogens, may help reduce the incidence of urinary tract infections.