Bladder injuries are the second most common type of urinary system injury. When the bladder is empty, it is located deep within the pelvis and is generally resistant to injury, except in cases of penetrating trauma or pelvic fractures. When the bladder is full, its walls become tense and thin, making it more susceptible to damage.

Etiology

Open Injuries

Penetrating injuries caused by gunshots or sharp instruments are often complicated by visceral injuries to the rectum, vagina, or other organs, resulting in the formation of abdominal wall urinary fistulas, vesicorectal fistulas, or vesicovaginal fistulas.

Closed Injuries

When the bladder is full, trauma such as a blow or compression to the lower abdomen easily causes bladder damage. Pelvic fractures may result in bone fragments directly puncturing the bladder wall. Prolonged labor can lead to ischemic necrosis of the bladder wall when it is compressed between the fetal head and the pubic symphysis, potentially resulting in a vesicovaginal fistula.

Iatrogenic Injuries

These are observed during diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as cystoscopy, transurethral resection for conditions like bladder neck obstruction, prostate issues, or bladder cancer. Injuries may also occur during pelvic surgeries, inguinal hernia repairs, tension-free vaginal tape placement for stress urinary incontinence, or vaginal surgeries, occasionally affecting the bladder.

Pathology

Contusion

This involves injury limited to the bladder's mucosa or superficial muscle layer without perforation of the bladder wall. Urinary extravasation does not occur, but hematuria may be present.

Bladder Rupture

Bladder rupture can be classified into extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal types.

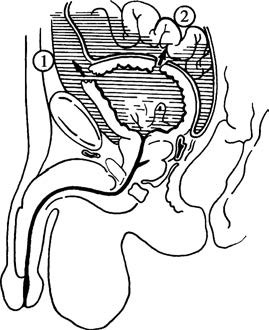

Figure 1 Bladder injuries (rupture)

1, Extraperitoneal type

2, Intraperitoneal type

Extraperitoneal Rupture

This involves isolated rupture of the bladder wall with the peritoneum remaining intact. Urine readily extravasates into the surrounding tissues such as the perivesical area, retropubic space, pelvic fascia to the pelvic floor, or around the ureters, possibly extending to the kidney region. Ruptures of the anterior bladder wall are the most common and are often associated with pelvic fractures.

Intraperitoneal Rupture

This occurs when the bladder wall rupture is accompanied by peritoneal rupture, leading to communication between the rupture site and the peritoneal cavity where urine spills, potentially causing peritonitis. Injuries to the bladder's posterior wall or dome are common in this type.

Clinical Manifestations

Hematuria and Difficulty Urinating

Mild bladder contusion may result in small amounts of terminal hematuria, while more severe bladder injuries can cause gross hematuria throughout urination. In some cases, bladder blood clots may obstruct the urethra, making urination difficult.

Abdominal Pain

Extraperitoneal ruptures may result in urinary extravasation and hematoma formation, causing lower abdominal pain, tenderness, and muscle rigidity. Digital rectal examination may reveal a full and tender anterior rectal wall. Intraperitoneal ruptures often lead to acute peritonitis due to urine leakage into the abdominal cavity.

Urinary Fistula

Open injuries may result in leaking of urine from a body surface wound. If the bladder communicates with the rectum or vagina, urine may leak through the anus or vagina. In closed injuries, urinary extravasation may become infected and rupture, forming a urinary fistula.

Local Symptoms

Swelling, hematoma, and bruising of the skin in the affected area may be observed.

Diagnosis

Medical History and Physical Examination

Following trauma to the lower abdomen or pelvis, the presence of abdominal pain, hematuria, and difficulty urinating, along with tenderness in the suprapubic region, may indicate extraperitoneal bladder rupture. A full abdomen with severe pain, muscle rigidity, tenderness, rebound tenderness, and shifting dullness may suggest intraperitoneal bladder rupture.

Catheterization Test

After inserting a catheter into the bladder, the drainage of more than 300 ml of clear urine can typically exclude bladder rupture. The absence or drainage of only a small amount of blood-stained urine raises the likelihood of bladder rupture. In such cases, 200–300 ml of sterile saline may be instilled into the bladder through the catheter and then withdrawn after a short period. Reduced withdrawal volumes point to leakage, while increased volumes indicate reflux of fluid into the abdominal cavity. A significant discrepancy in fluid inflow and outflow is often indicative of bladder rupture.

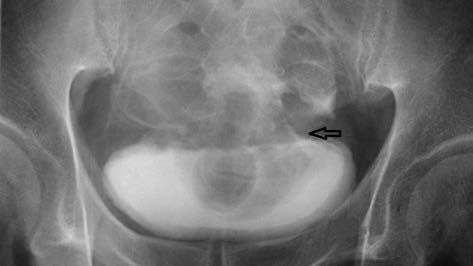

Cystography

Approximately 300 ml of 15% diatrizoate may be injected into the bladder through a catheter, followed by the acquisition of anterior and posterior radiographic images. After removing the contrast agent, additional images are taken. Extravasation of contrast outside the bladder wall and remaining contrast in extra-vesical regions confirm bladder rupture. In cases of intraperitoneal rupture, the intestinal loops may appear outlined by the contrast.

Figure 2 Radiographic image of bladder rupture

Retrograde Urethrography

Blood at the urethral opening or difficulty in passing a catheter may necessitate retrograde urethrography to rule out urethral injury.

Treatment

Emergency Management

Management includes anti-shock treatment and the timely and appropriate use of antibiotics to prevent infection.

Conservative Treatment

Most cases of extraperitoneal bladder injury can be treated non-surgically through continuous drainage. A catheter is inserted into the urethra for continuous urinary drainage for approximately ten days, along with the use of antibiotics to prevent infection. Spontaneous healing of the rupture is often observed.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention is required for bladder ruptures accompanied by severe bleeding or urinary extravasation. In cases of extraperitoneal rupture, a lower midline abdominal incision is made to expose the extraperitoneal bladder, which is then incised. Urinary extravasation is cleared, and the bladder rupture is repaired. For intraperitoneal ruptures, an abdominal exploration is performed to assess and address injuries to any other organs. Intraperitoneal fluid is aspirated, and the peritoneum and bladder wall are repaired in layers. Laparoscopic bladder repair may also be performed.

If bladder neck tears are present, accurate repair using absorbable sutures is required. After bladder repair, a Foley catheter or suprapubic cystostomy is used to ensure continuous urinary drainage for two weeks.

Management of Complications

Complications are primarily related to infection and, in severe cases, may lead to septicemia and peritonitis. Early surgical treatment and the use of antibiotics can reduce complications. Pelvic hematomas are best left intact to avoid massive bleeding and the risk of infection. Selective pelvic arterial embolization may be employed to manage uncontrollable bleeding.