The ureter is located in the retroperitoneal space, where it is well-protected by surrounding tissues, making trauma-induced ureteral injuries rare. Most ureteral injuries are iatrogenic in nature. These injuries are often overlooked or misdiagnosed and are frequently identified only after symptoms develop, leading to delayed treatment.

Etiology

Iatrogenic Injuries

Injuries related to intraluminal ureteral procedures: Ureteral perforation, laceration, avulsion, or rupture may occur during procedures such as retrograde ureteral catheterization, dilation, biopsy, ureteroscopy, or stone extraction (or lithotripsy). Ureteral stenosis, kinking, adhesions, or inflammation increase the risk of such injuries.

Injuries related to extraluminal ureteral surgical interventions: These injuries often occur during open or laparoscopic surgeries in the pelvis and retroperitoneum, including colectomy, rectal resection, hysterectomy, major vascular surgeries, ovarian tumor resection, and retropubic urethropexy. Complex anatomy, unclear surgical fields, rapid hemorrhage control, and clamping or ligation with large instruments contribute to the risk of ureteral damage.

Exogenous Trauma

Ureteral injuries caused by external trauma are exceedingly rare, accounting for less than 4% of penetrating injuries and less than 1% of blunt injuries. These injuries are more commonly observed in gunshot wounds and, infrequently, in stabbing injuries. Additionally, motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights may result in ureteral tears.

Radiation-Induced Injury

Radiation therapy for conditions such as cervical cancer, bladder cancer, or prostate cancer can cause edema, hemorrhage, and necrosis of the ureteral wall, leading to urinary fistulas or the formation of fibrotic scar tissue, which in turn results in ureteral strictures or obstruction.

Pathology

Ureteral injuries encompass contusion, perforation, ligation, clamping, transection, laceration, twisting, and ischemia or necrosis following extensive stripping of the adventitia. Transection or rupture of the ureteral wall can lead to retroperitoneal urinary extravasation or peritonitis, with the associated risk of sepsis following infection. Ligation of the ureter may cause hydronephrosis or even renal atrophy on the affected side. Clamping, extensive adventitial stripping, or securing the ureter within a vaginal stump may lead to ischemic necrosis at the site of injury, generally resulting in urinary extravasation or fistula formation within 1–2 weeks. Concomitant ureteral strictures may lead to hydronephrosis in the affected kidney.

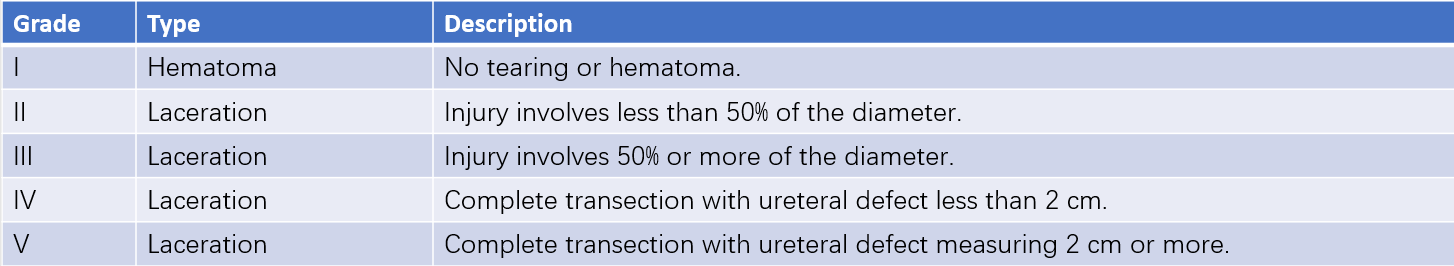

Table 1 Grading of ureteral injury severity

According to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) injury severity scale, ureteral injuries can be classified into five grades based on the type and extent of damage.

Clinical Manifestations

Hematuria

Hematuria is commonly observed in cases of mucosal injuries to the ureter. However, the severity of hematuria does not always correlate with the extent of injury.

Urinary Extravasation

Urine may leak from the site of injury into the retroperitoneal space or even the abdominal cavity, leading to lumbar pain, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, localized swelling, palpable masses, tenderness, and infection.

Urinary Fistula

Urine may discharge through wounds in the abdominal wall, the vagina, or even the intestinal wall.

Obstructive Symptoms

Compression, blockage, ligation, or suturing of the ureter can lead to varying degrees of obstruction, resulting in increased pressure in the renal pelvis. Symptoms may include ipsilateral lumbar pain, muscle tension in the lumbar region, tenderness in the renal area, and fever. Complete obstruction of one or both ureters, particularly in cases of solitary kidneys, may lead to anuria.

Diagnosis

During the evaluation of injuries or procedures involving the abdomen or pelvis, the trajectory of the ureter and the presence of urine leakage should be carefully assessed to identify potential ureteral injuries. Common diagnostic methods include:

Intravenous Indigocarmine Dye Test

If ureteral injury is suspected during surgery, intravenous administration of indigo carmine can identify damage, as blue-colored urine will be observed leaking from the site of injury.

Intravenous Urography (IVU)

IVU can reveal urinary extravasation, fistulas, or obstruction at the site of ureteral injury.

Retrograde Pyelography

This technique involves advancing a catheter to the site of injury, where resistance may be encountered. Injection of contrast material can reveal obstruction or extravasation of the contrast.

Figure 1 Retrograde pyelography image of ureteral injuries.

Ultrasound

Ultrasonography can detect hydronephrosis secondary to obstruction, as well as identify urinary extravasation.

Radionuclide Renography

Renal scintigraphy can identify whether upper urinary tract obstruction is present in the affected kidney.

CT Imaging

CT scans can depict changes in the injury site, including the presence of urinomas, perirenal abscesses, hydronephrosis, and urinary fistulas. CT urography (CTU) can assess patency at the site of injury and identify contrast medium extravasation.

Treatment

Early Management

After addressing shock and other severe concurrent injuries, prompt intervention is undertaken for ureteral injuries. Percutaneous nephrostomy may be performed on the affected side when the patient cannot tolerate surgery, helping to preserve renal function. Thorough drainage is employed to manage urinary extravasation and prevent secondary infection.

Mucosal Injury and Bleeding caused by Retrograde Ureteral Catheterization

Typically, no special treatment is required; however, severe cases may require placement of a double-J ureteral stent for drainage, which is removed after 1–2 weeks.

Minor Clamping Injuries or Mild Lacerations

Placement of a double-J ureteral stent for drainage is often sufficient, with removal after two weeks.

Accidental Ureteral Ligation

If accidental ligation is discovered during surgery, immediate release of the ligation is performed. If ischemic necrosis is present, the ischemic segment of the ureter is resected, followed by end-to-end anastomosis. A double-J stent is left in place for 3–4 weeks.

Ureteral Transection or Partial Defects

High-level transections are repaired using end-to-end anastomosis if there is no tension at the site. Injuries in the lower third portion, accompanied by partial defects, are managed with ureteroneocystostomy or reconstructing the lower ureter using a bladder wall flap. Extensive ureteral defects may require alternative procedures such as tongue mucosa grafting, appendix or ileal ureter substitution, ureterocutaneostomy, or autotransplantation of the affected kidney.

Management of Late Complications

Ureteral Strictures

Ureteral strictures may undergo dilation, followed by insertion of a ureteral stent for drainage. Severe strictures or failed stenting may require surgical techniques such as adhesiolysis or resection of the stenotic segment with end-to-end anastomosis.

Urinary Fistula

Skin fistulas or ureterovaginal fistulas typically emerge approximately three months after injury. Nephrostomy is often performed on the affected side while waiting for local edema and inflammatory responses to subside. Subsequent repair, reconstruction, or surgical ureter-bladder anastomosis may be required.

Complete Ureteral Obstruction

In cases where complete obstruction caused by injury cannot be resolved immediately, nephrostomy is utilized as an interim measure, with ureteral reconstruction undertaken three months later.

Severe Renal Functional Impairment or Failure

In cases of significant hydronephrosis or infection caused by strictures leading to substantial renal damage or loss of renal function, nephrectomy of the affected kidney may be considered if the contralateral kidney remains functional.