Renal injuries are often part of severe multiple trauma cases, predominantly seen in adult males, and various types of renal injuries may coexist in the same patient.

Etiology

Renal injuries can be classified into open injuries and closed injuries based on the cause of trauma:

Open Injuries

Also known as penetrating injuries, these are caused by sharp objects such as bullets or blades, creating wounds that communicate with the external environment.

Closed Injuries

Also referred to as blunt injuries, these are more commonly encountered in clinical practice and result from direct forces (e.g., impact, falls, compression) or indirect forces (e.g., contrecoup injuries, violent twisting). These injuries generally do not involve external wounds communicating with the environment.

Additionally, when the kidney is affected by preexisting conditions (such as hydronephrosis, kidney tumors, renal tuberculosis, or cystic diseases), it becomes more prone to damage. Even minor trauma may result in severe "spontaneous" renal rupture. Medical procedures such as percutaneous renal biopsy, nephrostomy, and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy can also cause varying degrees of renal injury.

Pathology

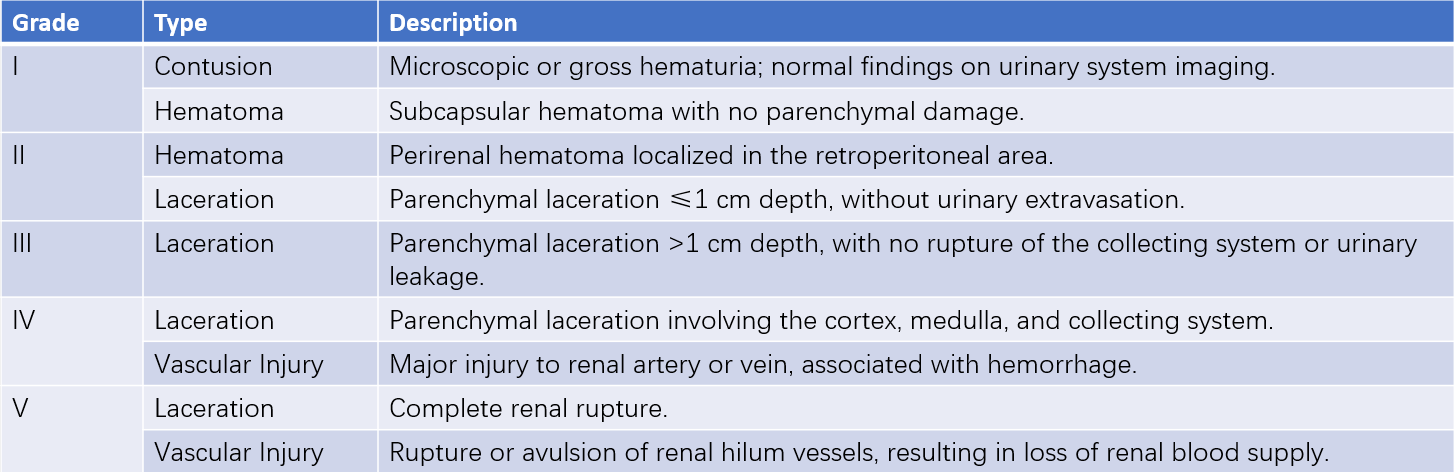

The renal injury grading standard developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma in 1989 is the most widely used clinical classification.

Table 1 Grading system for renal injuries

Note: For bilateral injuries graded as Grade III, the classification is upgraded to Grade IV.

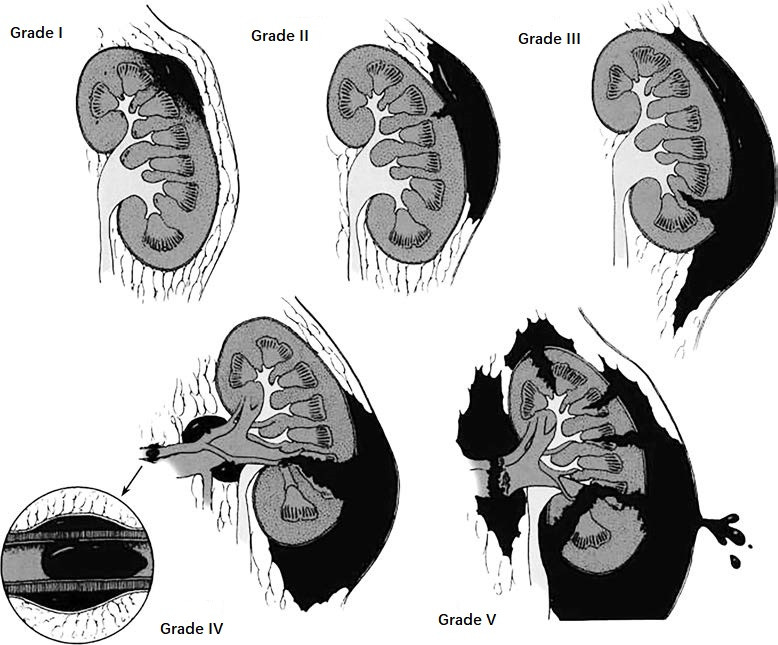

Figure 1 Grading of renal injuries.

Late-Stage Pathological Changes

Persistent urinary extravasation may lead to the formation of urinomas. Hematoma and urinary extravasation can cause tissue fibrosis, which may compress the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ), leading to hydronephrosis. Open renal injuries occasionally result in arteriovenous fistulas or pseudoaneurysms. Partial renal parenchymal ischemia or fibrosis around the renal pedicle can compress the renal artery, potentially causing renovascular hypertension.

Clinical Manifestations

Shock

Severe renal laceration, rupture of renal pedicle blood vessels, or combined injury to other organs can lead to significant blood loss and shock, posing a life-threatening risk.

Hematuria

Renal contusion may cause microscopic hematuria or mild gross hematuria. Laceration involving the region near the collecting system (calyces or renal pelvis) often results in marked hematuria. Complete laceration of the renal parenchyma is associated with profuse gross hematuria throughout the urinary cycle. The severity of hematuria does not always correlate with the extent of renal injury.

Pain

Subcapsular hematomas, renal perirenal soft tissue damage, bleeding, or urinary extravasation may cause ipsilateral lumbar and abdominal pain. If blood or urine enters the abdominal cavity or coexists with intra-abdominal organ injuries, generalized abdominal pain and peritoneal irritation may occur. Renal colic can arise when blood clots pass through the ureter.

Abdominal or Lumbar Mass

Blood or urine accumulating in perirenal tissues may lead to localized swelling and palpable masses, often accompanied by tenderness and muscle rigidity.

Fever

Resorption of hematomas can cause fever. Infection associated with perirenal hematomas or urinary extravasation may lead to perirenal abscesses or purulent peritonitis, accompanied by systemic intoxication symptoms.

Diagnosis

Patient History and Physical Examination

All patients with abdominal, dorsal, or lower thoracic trauma, including those with contrecoup injuries, should be evaluated for renal injury, even in the absence of classical symptoms such as lumbar pain, masses, or hematuria. The severity of symptoms does not always correspond to the degree of renal damage.

Laboratory Testing

A continuous decline in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels suggests active bleeding. Renal injuries may be overlooked in severe thoracic or abdominal trauma, emphasizing the need for timely urinalysis and imaging studies to avoid missed diagnoses.

Imaging Studies

Early imaging studies play a crucial role in identifying the location and severity of renal injury, detecting urinary extravasation, and assessing the condition of the contralateral kidney. Available imaging modalities include:

- Ultrasound: Provides information on the location and extent of renal injury, the presence of subcapsular or perirenal hematomas, urinary extravasation, associated organ injuries, and contralateral renal status. It also evaluates the condition of the renal pedicle vessels.

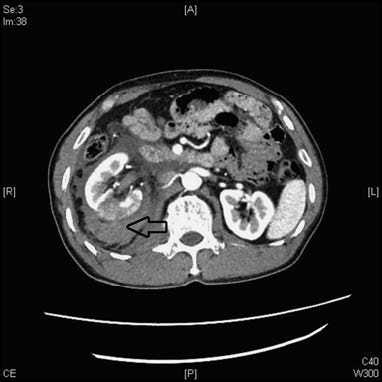

- CT: Non-contrast and contrast-enhanced CT effectively visualize the degree of renal parenchymal laceration, the extent of urinary extravasation and hematomas, renal perfusion, and the relationship with other organs. Contrast-enhanced CT is considered the gold standard for imaging the genitourinary system in renal injuries. CT urography (CTU) can identify reduced contrast excretion in the damaged kidney and detect contrast extravasation. CT angiography (CTA) facilitates assessment of renal artery and parenchymal damage and detects renal arteriovenous fistulas or traumatic renal artery aneurysms. Complete obstruction of the renal artery suggests traumatic thrombosis.

- Other Imaging Modalities: MRI has diagnostic capabilities similar to CT but is more specific in identifying hematomas. Conventional IVU and arterial angiography can assess renal injury but are generally not first-line options in clinical practice.

Figure 2 CT imaging of renal injuries.

Indications for renal imaging include:

- Penetrating trauma (to the abdomen, flank, or lower chest) potentially involving the kidney, with hemodynamic stability sufficient for imaging.

- Blunt trauma associated with significant acceleration or deceleration forces, particularly from high-speed motor vehicle accidents or high falls.

- Blunt trauma with gross hematuria.

- Blunt trauma with microscopic hematuria and hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg at any stage during evaluation or resuscitation).

- Pediatric patients with >5 red blood cells per high-power field on urinalysis.

Treatment

Non-surgical management is the standard treatment for patients with hemodynamic stability and well-staged Grade I–III renal injuries. Patients with Grade IV and V injuries typically require surgical exploration, although with thorough staging and appropriate selection, higher-grade injuries can also be managed conservatively.

Emergency Management

Patients with massive bleeding or shock require urgent resuscitation measures, including transfusion, fluid replacement, and anti-shock therapy. Concurrently, the presence of additional organ injuries must be assessed, and preparation for surgical exploration should be undertaken.

Conservative Management

Absolute Bed Rest

Patients should remain on strict bed rest for 2–4 weeks, and physical activity should not resume until the condition stabilizes and hematuria resolves. Following recovery, patients are advised to avoid heavy physical labor or competitive sports for 2–3 months.

Close Monitoring

Vital signs should be regularly measured. Attention should be given to changes in lumbar-abdominal mass size, alterations in urine color, and fluctuations in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

Volume and Energy Replacement

Blood volume and energy levels should be replenished promptly, and water-electrolyte balance must be maintained to support adequate urine output.

Antibiotic Usage

Early, appropriate administration of antibiotics helps prevent infections.

Medications

Analgesics, sedatives, and hemostatic agents should be used judiciously.

Surgical Management

Indications for renal exploration or rapid vascular embolization after trauma are categorized into absolute and relative criteria:

Absolute indications include:

- Hemodynamic instability, such as shock.

- Enlarging or pulsatile renal hematomas (often indicative of renal artery rupture).

- Suspected avulsion of renal vascular pedicles.

- Ureteropelvic junction rupture.

Relative indications include:

- Urinary extravasation with significant disruption of renal parenchymal blood supply.

- Renal injury accompanied by damage to the colon or pancreas.

- Arterial thrombosis.

- Urinary extravasation caused by parenchymal injury.

The surgical approach may involve either an abdominal incision or a flank incision. If intra-abdominal organ injuries are suspected, evaluation and management of these injuries should precede the dissection of the retroperitoneal space. The renal vascular pedicle is isolated and temporarily controlled before incising the renal fascia and fat capsule to access the injured kidney. Hematomas are removed swiftly, and the surgical management may involve kidney repair, partial nephrectomy, or total nephrectomy, depending on the specific situation. Total nephrectomy is considered only when severe full-thickness laceration or irreparable injury to renal pedicle vessels threatens the patient's survival. Renal artery angiography and selective vascular embolization are increasingly common diagnostic and therapeutic methods in the management of renal injuries. Traumatic pseudoaneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas can be effectively treated through embolization guided by angiography.

Management of Complications

Perirenal urinoma or abscess: requires puncture drainage or surgical incision and drainage.

Ureteral stricture or hydronephrosis may necessitate reconstructive surgery or nephrectomy.

Malignant hypertension can be managed with angioplasty at the site of vascular stenosis or nephrectomy.

Selective embolization of renal artery branches may provide effective resolution for persistent severe hematuria.