Lower gastrointestinal bleeding refers to hemorrhage caused by lesions located in the small intestine, cecum, appendix, colon, and rectum below the Treitz ligament, generally excluding bleeding from hemorrhoids or anal fissures. Over 90% of primary bleeding lesions in lower gastrointestinal bleeding are located in the colon, with the remainder occurring in the small intestine. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding accounts for approximately 15% of all gastrointestinal bleeding cases, with massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding being even rarer.

Hematochezia is the most common clinical manifestation, and the color of the stool varies depending on the amount, location, and speed of bleeding. Overt bleeding often presents as jam-like stool, dark red stool, or bright red stool, whereas occult bleeding may result in stools with a normal appearance.

Etiology

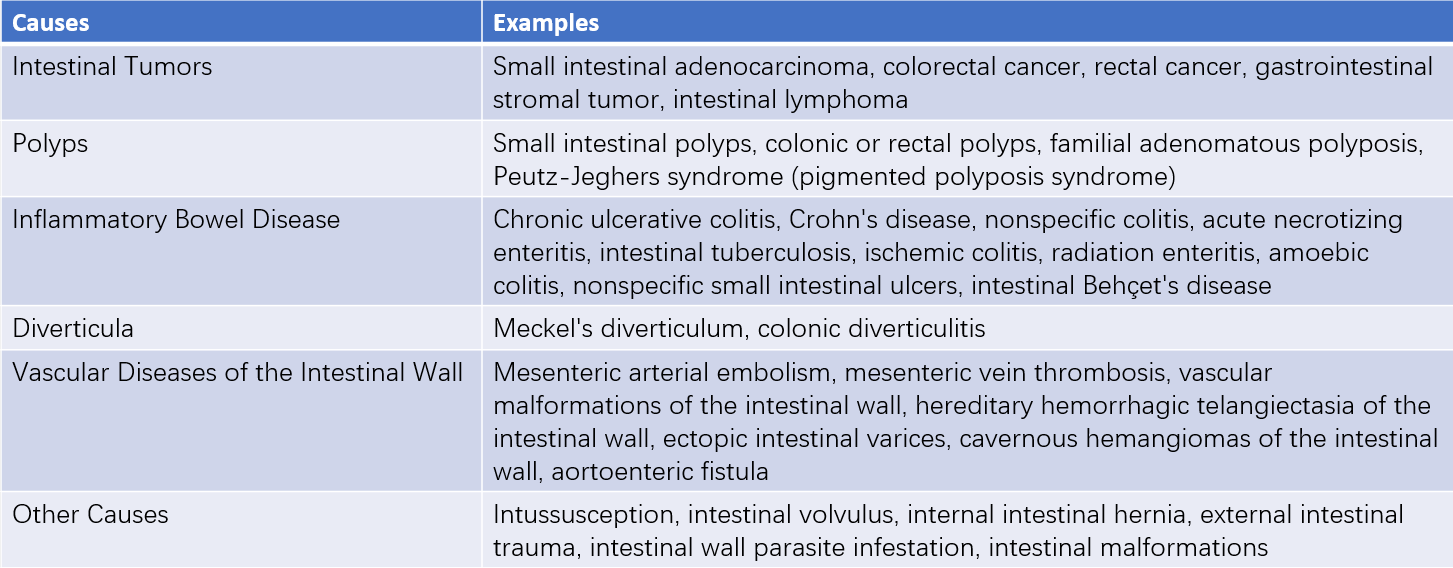

A variety of conditions lead to lower gastrointestinal bleeding, with common causes including colorectal cancer, intestinal polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticular disease, and vascular conditions affecting the intestinal wall.

Table 1 Common causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Diagnosis

Medical History

A thorough investigation of the medical history is crucial. The patient's age is closely associated with the causes of hematochezia. Intussusception and hemorrhagic colitis are commonly seen in children and adolescents, while colorectal tumors and vascular lesions are more prevalent in middle-aged and elderly individuals. A family history of hereditary diseases may suggest conditions such as familial colonic polyposis or Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Vascular malformations of the intestinal wall may cause acute massive bleeding or recurrent intermittent bleeding of variable severity. Hematochezia accompanied by fever and abdominal pain suggests infectious conditions such as infectious colitis, typhoid enteritis, or intestinal tuberculosis. Changes in bowel habits, irregularly shaped blood in the stool, vague abdominal pain, anemia, or unexplained weight loss might indicate intestinal malignancies.

Physical Examination

Attention should be directed to signs such as abdominal distension, palpable masses, tenderness, rebound tenderness, and abnormal bowel sounds. Routine digital rectal examination is necessary, as approximately two-thirds of rectal cancer cases can be detected this way. It also helps avoid misdiagnosing hematochezia as hemorrhoidal bleeding, thereby preventing diagnostic delays.

Laboratory Tests

Dynamic monitoring of blood parameters such as red blood cell count and hemoglobin levels is useful for assessing the volume of blood loss. White blood cell count and differential analysis may aid in diagnosing inflammatory bowel diseases. Serum tumor marker tests, especially carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), are helpful for detecting malignancies within the intestine. Persistent elevation of CEA levels provides supporting evidence for diagnosing colorectal cancer.

Auxiliary Examinations

Colonoscopy

Approximately 80% of conditions causing lower gastrointestinal bleeding originate from the colon or rectum. Colonoscopy enables direct visualization of the lesion, providing information on its location, number, size, and extent. Furthermore, tissue biopsies from the lesion can be obtained for pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis.

Small Intestinal Endoscopy

If bleeding is suspected to originate from the small intestine, capsule endoscopy serves as a convenient tool to evaluate the morphology and scope of the lesion with minimal discomfort to the patient. However, it has limitations in accurately locating lesions and does not permit biopsy sampling.

Colonic Barium Enema X-rays

Barium enema imaging is useful for assessing the morphology, location, number, size, and infiltration range of colonic tumors.

Selective Arterial Angiography

For severe acute bleeding, especially when suspected to stem from the small intestine, selective angiography of the superior mesenteric artery provides reliable diagnostic insight. It can help identify bleeding foci from the small intestine below the Treitz ligament to the splenic flexure of the colon. Angiography of the inferior mesenteric artery can detect bleeding sites from the splenic flexure to the rectum.

Radionuclide Imaging

Abdominal γ-scintigraphy using red blood cells labeled with 99mTc is commonly performed to investigate bleeding in the small intestine. Multiple scans can detect the site of bleeding through radioactive concentration imaging, enabling localization of the source of bleeding.

Treatment

The incidence of shock caused by acute massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding is less than 10%. Most patients can achieve hemostasis through non-surgical treatment or undergo elective surgery after identifying the bleeding site and the underlying condition.

Non-Surgical Treatment

For patients with acute massive bleeding, close monitoring of vital signs, central venous pressure, and urine output is critical. Correction of water, electrolyte, and acid-base imbalances, as well as effective fluid resuscitation to restore blood volume and maintain circulation, is essential. Intravenous administration of hemostatic agents is utilized, along with active diagnostic efforts to determine the cause and site of bleeding.

Selective Arterial Interventional Therapy

A catheter is super-selectively directed to the artery supplying the bleeding lesion for vascular embolization to achieve hemostasis.

Endoscopic Hemostasis via Fiberoptic Colonoscopy

For superficial mucosal erosions in the intestine, hemostatic agents such as thrombin spray, medical adhesives, or norepinephrine may be applied directly. For bleeding associated with conditions like hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia or small hemangiomas, high-frequency electrocoagulation or laser therapy may be employed. Solitary vascular tumors in the intestinal wall may be managed using snare ligation techniques.

Surgical Treatment

Emergency Exploratory Laparotomy

For patients with significant uncontrolled bleeding, where the bleeding site and the nature of the lesion remain undetermined despite various diagnostic methods, emergency exploratory laparotomy may be required. Due to the large amount of blood accumulated within the intestinal lumen, identifying the bleeding site often presents substantial challenges. Systematic exploration from the proximal jejunum distally, with careful observation of vascular patterns in the intestinal wall or mesentery and palpation for elevated lesions, is employed. Intraoperative selective arterial angiography and fiberoptic enteroscopy may also be utilized for localization of bleeding. Intestinal segment resection in the absence of a clear bleeding source is generally not recommended.

Elective Surgery

For benign lesions with a confirmed bleeding site that fail to respond adequately to non-surgical treatment, elective surgery may be considered. The goal is to resect the primary lesion, address the underlying cause, and prevent recurrent bleeding. For intestinal cancer, curative surgery is preferred, whereas palliative resection of the primary tumor may be performed to control bleeding in advanced malignancies causing massive hemorrhage.