Pancreatic cancer, also known as pancreatic carcinoma, has an insidious onset and a poor response to treatment, with extremely unfavorable prognosis. The disease is more common in individuals over 40 years old and occurs more frequently in men than women. In recent years, both its incidence and mortality rates have been increasing. Pancreatic cancer is most frequently located in the head and neck of the pancreas, followed by the body and tail, while diffuse or multicentric lesions are rare.

Pathological Types

According to the WHO histological classification, malignant epithelial neoplasms of the pancreas primarily include ductal adenocarcinoma and acinar cell carcinoma. Ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for 90% of pancreatic cancers. Less common types include mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, and adenosquamous carcinoma.

Staging

The 8th edition of the TNM staging system by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is used for pancreatic cancer staging.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Risk factors associated with the development of pancreatic cancer include smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, and chronic pancreatitis. Genetic predisposition is present in 5%–10% of cases.

Clinical Manifestations

Pancreatic cancer has an insidious onset, and its symptoms are non-specific, making early diagnosis challenging. Common clinical features include upper abdominal pain, abdominal distention, jaundice, back pain, and weight loss. The symptomatology varies depending on the tumor's location.

Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain is often the first symptom. In the early stages, tumor compression causes varying degrees of pancreatic duct obstruction, dilation, and increased pressure, resulting in vague, dull, or distending pain in the upper abdomen. In the middle and late stages, tumor invasion of the retroperitoneal nervous plexus can lead to persistent, severe upper abdominal pain, radiating to the back. Pain tends to worsen in the supine position but is alleviated when bending forward, curling up, sitting, or lying on the side, which is referred to as "pancreatic pain."

Jaundice

Jaundice is the most prominent clinical feature of pancreatic head cancer and generally progresses over time. Symptoms include dark-colored urine similar to tea and pale, clay-colored stools, often accompanied by itchy skin. This is caused by tumor compression or invasion of the common bile duct. In cases where pancreatic head cancer compresses the bile duct, jaundice becomes more pronounced, and an enlarged but non-tender gallbladder can be palpated, referred to as Courvoisier’s sign.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Symptoms such as loss of appetite, bloating, diarrhea, or constipation may occur. Some patients may also experience nausea and vomiting. Tumor invasion of the duodenum can result in upper gastrointestinal obstruction or bleeding.

Weight Loss

Weight loss is a prominent symptom of pancreatic cancer. Patients may develop emaciation and fatigue due to reduced food intake, impaired digestion, lack of sleep, and cancer-induced catabolism. In the late stages, cachexia may occur.

Other Symptoms

A small number of patients may present with acute abdomen. Newly diagnosed diabetes, depression, or anxiety symptoms may also occur in some cases. In the late stages, a palpable, hard, fixed mass may be detected in the upper abdomen, often with ascites. Some patients exhibit metastases to the left supraclavicular lymph nodes, while pelvic metastases can be identified through rectal examination.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis primarily involves laboratory and imaging studies.

Laboratory Tests

Biochemical Tests

Pancreatic head cancers in the early stages may show transient elevations in blood and urine amylase levels, increased fasting or postprandial blood glucose, and abnormal glucose tolerance tests. In cases of biliary obstruction, elevated serum total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases may be observed.

Tumor Marker Tests

Tumor markers commonly used include CA19-9, CEA, CA242, and CA125. Among these, CA19-9 is the most significant and is frequently utilized for auxiliary diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Imaging Studies

CT

Thin-slice contrast-enhanced CT scanning and 3D reconstruction are the preferred imaging modalities. These techniques provide clear visualization of the tumor's size, location, density, and vascular involvement, as well as its relationship with adjacent structures. They are essential for assessing tumor resectability.

MRI or Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

MRI provides clear visualization of enlarged peripancreatic lymph nodes and liver metastases, while MRCP can identify the sites and degree of pancreatic and bile duct obstruction.

PET-CT

This technique highlights the metabolic activity of tumors and serves as an advantage in assessing extra-pancreatic metastases and total tumor burden.

EUS

Endoscopic ultrasound serves as an important supplement to CT and MRI, allowing the detection of tumors smaller than 1 cm. EUS-guided biopsy is an effective method for preoperative pathological diagnosis.

Treatment

Resectability Assessment

Pancreatic cancer can be classified based on its relationship with surrounding vasculature and the presence of distant metastases. The categories include resectable pancreatic cancer, borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, locally advanced pancreatic cancer, and metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Surgical Treatment

Radical Surgery

For patients with resectable pancreatic cancer who are in good general condition, radical surgery is prioritized. The choice of surgical method is based on the tumor's location.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure)

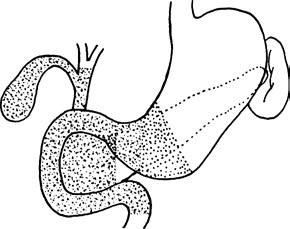

This is the classic surgical method for treating pancreatic head cancer. It involves removing the pancreatic head (including the uncinate process), the bile duct below the common hepatic duct (including the gallbladder), the distal stomach, the duodenum, and part of the jejunum. Corresponding lymphatic and adipose tissue in the region is also removed. Reconstruction of the digestive tract is then performed, including pancreaticojejunostomy, hepaticojejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy.

Figure 1 Scope of resection in the Whipple procedure

Distal Pancreatectomy with Splenectomy

For cancers of the pancreatic body and tail, distal pancreatectomy combined with splenectomy is typically performed, along with radical lymph node dissection.

Palliative Surgery:

For unresectable pancreatic cancer, palliative surgical treatments are available. In cases of biliary or duodenal obstruction, endoscopic stent placement or biliary-enteric or gastro-enteric anastomosis may be performed. For patients with biliary obstruction who fail stent placement, percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) can be used to relieve jaundice.

Multimodal Therapy

Neoadjuvant Therapy

This approach may reduce tumor size and downstage pancreatic cancer to increase the likelihood of surgical resection. It also reduces the risk of recurrence and improves long-term outcomes. Neoadjuvant therapy is recommended as the first-line treatment for patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer and locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

For patients with good physical performance, combination chemotherapy regimens such as FOLFIRINOX (a combination of 5-FU, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) or nab-paclitaxel combined with gemcitabine are often used.

For patients with poorer physical performance, single-agent chemotherapy, such as gemcitabine or fluoropyrimidines, may be administered.

Postoperative Adjuvant Therapy

All patients who undergo radical surgery for pancreatic cancer should receive adjuvant chemotherapy. The specific regimen can be determined based on the patient's physical condition and the response to neoadjuvant therapy.

Multimodal Therapy for Non-Surgical Patients

For patients who are not candidates for surgery, multimodal treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy may be applied. Treatment plans can be adjusted based on the response to therapy. For patients with end-stage pancreatic cancer, supportive care focusing on nutritional support, pain control, and symptom management is implemented to improve quality of life.

Recent advancements in molecular targeted therapies and immunotherapies have provided new possibilities for pancreatic cancer treatment, though their efficacy still requires further investigation.