Acute pancreatitis is a common acute abdominal condition with complex and variable presentations, ranging from mild to severe. Mild cases often manifest as pancreatic edema, are usually self-limiting, and have a favorable prognosis. Severe cases may involve pancreatic necrosis, complications such as peritonitis and shock, as well as secondary multi-organ dysfunction, resulting in a high mortality rate.

Acute pancreatitis is associated with numerous risk factors, primarily the following:

Biliary Diseases

Biliary disorders account for more than 50% of cases, commonly referred to as biliary pancreatitis. Gallstones can obstruct the distal common bile duct, leading to bile reflux into the pancreatic duct through a "common channel." Bile salts can directly increase cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration in acinar cells, causing acinar cell necrosis, elevated intraductal pressure, microscopic pancreatic duct rupture, and leakage of pancreatic enzymes into periacinar tissues. Trypsinogen is activated by collagenase into trypsin, which in turn activates phospholipase A, elastase, and chymotrypsin. These enzymes induce "autodigestion" of the pancreas, triggering acute pancreatitis.

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol is one of the common causes of acute pancreatitis. Ethanol exerts a direct toxic effect on the pancreas, stimulates pancreatic secretion, and causes edema of the duodenal papilla and spasm of the sphincter of Oddi. These effects result in increased intraductal pressure and pancreatic duct rupture.

Metabolic Disorders

Hyperlipidemia and hypercalcemia can both lead to acute pancreatitis. With improved living standards, the incidence of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis has increased compared to previous years.

Duodenal Fluid Reflux

Elevated pressure in the duodenum can cause reflux of duodenal fluid into the pancreatic duct. Specific causes include duodenal diverticulum, anatomical anomalies at the pancreatobiliary junction, annular pancreas, inflammatory strictures of the duodenal papilla or distal duodenum, afferent loop obstruction following partial gastrectomy, and dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi.

Iatrogenic Factors

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) can cause acute pancreatitis in approximately 2%–10% of patients. Pancreatic ductal anastomosis stenosis may also induce pancreatitis.

Neoplasms

Tumors such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) and pancreatic cancer can cause pancreatic duct obstruction, precipitating acute pancreatitis.

Drugs

Certain medications, including mesalamine (5-aminosalicylic acid), azathioprine, mercaptopurine, cytarabine, didanosine (2’,3’-dideoxyinosine), diuretics (e.g., furosemide and thiazides), estrogen, metronidazole, valproic acid, and acetaminophen, have been implicated in the development of acute pancreatitis.

Trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma, penetrating injuries, or surgical trauma may contribute to acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatic Circulatory Disturbances

Conditions such as hypotension, cardiopulmonary bypass, arterial embolism, vasculitis, and increased blood viscosity may impair pancreatic blood flow and result in acute pancreatitis.

Other Causes

Other factors include infections, pregnancy-related metabolic disturbances, genetic predisposition, and autoimmune diseases. A small proportion of cases with unknown etiology are classified as idiopathic acute pancreatitis.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis is complex and not yet fully elucidated. Most researchers believe that the disease results from abnormal activation of pancreatic enzymes within the acinar cells. The activation of pancreatic enzymes triggers autodigestion of the pancreatic parenchyma. Subsequently, acinar cells release inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-2, and IL-6. These cytokines recruit neutrophils and macrophages to the pancreas, which further release inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, reactive oxygen species (ROS), prostaglandins, platelet-activating factor, and leukotrienes, leading to a cascading inflammatory response.

In approximately 80%–90% of patients, the inflammatory cascade is self-limiting. However, in the remaining 10%–20% of cases, substantial inflammatory mediators enter systemic circulation, creating a vicious cycle of pancreatic injury and local and systemic inflammation. This process leads to persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sometimes multi-organ dysfunction, which forms the pathological basis for early mortality peaks in acute pancreatitis.

Pathology

The fundamental pathological changes of acute pancreatitis include pancreatic edema, congestion, hemorrhage, and necrosis.

Acute Edematous Pancreatitis

The lesions are mild and primarily localized to the body and tail of the pancreas. The pancreas is swollen, firm, and congested, with peripancreatic effusion. Fatty tissue within the abdominal cavity, especially the greater omentum, may exhibit scattered millet-sized or patchy yellowish-white saponification spots (calcium soaps formed from fatty acids). The ascitic fluid appears pale yellow. Microscopically, stromal congestion, edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration are observed, along with localized fat necrosis.

Acute Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Pancreatitis

This type is characterized by pancreatic parenchymal hemorrhage and necrosis. The pancreas is swollen, dark purple in color, with indistinct lobular structures. Necrotic areas appear gray-black, and, in severe cases, the entire pancreas becomes blackened. Saponification spots and fat necrosis are present in the abdominal cavity, with extensive tissue necrosis seen in the retroperitoneum. The ascitic fluid or retroperitoneal effusion often appears coffee-colored or dark reddish and turbid. Microscopically, fat necrosis, acinar destruction, and indistinct acinar lobular structures are evident. Necrosis of small vascular walls in the stroma is frequently accompanied by patchy hemorrhages and inflammatory cell infiltration.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical presentations of acute pancreatitis vary widely depending on the severity of the lesions.

Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain is the primary symptom and typically occurs suddenly after a heavy meal or alcohol consumption. The pain is severe, often located in the left upper quadrant, radiating to the left shoulder and left flank. It is continuous in nature. When the entire pancreas is involved, the pain may affect a wider area, presenting as a band-like radiation to the back.

Abdominal Distension

Abdominal distension commonly accompanies abdominal pain. It results from intestinal paralysis caused by stimulation of the abdominal nerve plexus. The severity of abdominal distension correlates with the degree of retroperitoneal inflammation and may be exacerbated by ascitic fluid accumulation. Bowel movements and gas passage cease. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome.

Nausea and Vomiting

These symptoms appear early in the course of the disease and are often severe and frequent. Vomit typically contains gastric and intestinal contents, occasionally appearing coffee-colored. Vomiting does not relieve abdominal pain.

Signs of Peritonitis

In edematous pancreatitis, tenderness is usually confined to the upper abdomen, often without significant muscle rigidity. In necrotizing pancreatitis, abdominal tenderness becomes more pronounced and may be accompanied by muscle rigidity and rebound tenderness, with a broader area of involvement that can affect the entire abdomen. Bowel sounds are diminished or absent. In patients with large amounts of abdominal effusion, shifting dullness may be positive.

Other Symptoms

Mild cases may present with no fever or only mild fever. Patients with concurrent biliary infection often experience chills and high fever. Persistent high fever is a common symptom in cases of pancreatic necrosis with infection. If gallstones are impacted or pancreatic head swelling compresses the common bile duct, jaundice may develop. Severe cases may present with rapid, thready pulses, hypotension, and even shock. Acute lung failure may lead to respiratory distress and cyanosis. Infected pancreatic necrosis can cause localized swelling, redness, and tenderness in the lumbar region. In rare cases, pancreatic hemorrhage can spread via retroperitoneal routes to the subcutaneous tissues, leading to large purplish-blue ecchymotic patches on the lumbar, flank, and lower abdominal skin (Grey-Turner's sign). If this occurs around the umbilicus, it is referred to as Cullen's sign. Some patients also present with hematemesis and melena. Hypocalcemia may cause tetany. Severe cases may show signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and central nervous system involvement, such as reduced sensitivity, confusion, or even coma.

Diagnosis

Laboratory Tests

Pancreatic Enzyme Measurements

Serum and urinary amylase measurements are commonly used diagnostic methods. Serum amylase levels begin to rise a few hours after the onset of the disease, peaking at 24 hours, and decreasing to normal within 4–5 days. Urinary amylase starts to increase 24 hours after onset, peaks at 48 hours, and usually returns to normal within 1–2 weeks. Diagnostic reference values for amylase differ depending on the testing methods, and the degree of elevation is not directly proportional to the severity of the disease.

Serum amylase levels may also increase in conditions such as gastrointestinal perforation, intestinal obstruction, cholecystitis, mesenteric ischemia, and mumps, so differential diagnosis is necessary. Elevated serum lipase levels provide higher specificity for diagnosis.

Other Parameters

These include elevated white blood cell counts, hyperglycemia, abnormal liver function tests, hypocalcemia, and acidosis. Diagnostic paracentesis with the extraction of blood-tinged or brownish exudative fluid with elevated amylase levels is helpful for diagnosis. Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels indicate more severe disease.

Imaging Diagnosis

Ultrasound

Ultrasound may reveal pancreatic enlargement and peripancreatic fluid collection. Edematous pancreas appears as uniformly hypoechoic, while coarse hyperechoic patterns may suggest hemorrhage or necrosis. The presence of biliary stones and bile duct dilation strongly suggests biliary pancreatitis. However, intestinal gas can interfere with the accuracy of ultrasound diagnosis.

CT Scan

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT is the most valuable imaging tool for diagnosis. It not only confirms acute pancreatitis but also determines the presence of pancreatic necrosis or infection. A diffusely enlarged pancreas with heterogeneous texture, areas of liquefaction, or honeycomb-like low-density regions without enhancement strongly suggests pancreatic necrosis.

MRI

MRI provides diagnostic information similar to CT. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) offers clear visualization of the bile and pancreatic ducts, aiding in the diagnosis of biliary stones and anatomical anomalies of the pancreatobiliary junction, which are important causes of pancreatitis.

Diagnostic Criteria

A diagnosis of acute pancreatitis can be made if two of the following three criteria are met:

- Abdominal pain consistent with the clinical manifestations of acute pancreatitis.

- Serum amylase and/or lipase levels more than three times the upper limit of normal.

- Imaging findings consistent with acute pancreatitis.

Severity Classification

Mild Acute Pancreatitis (MAP)

Comprising 60% of acute pancreatitis cases, MAP is characterized by the absence of organ failure and local or systemic complications. The main symptoms include upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Peritonitis may occur but is usually confined to the upper abdomen with mild signs. Recovery typically occurs within 1–2 weeks with timely fluid therapy, and mortality is extremely low.

Moderately Severe Acute Pancreatitis (MSAP)

Occurring in approximately 30% of cases, MSAP involves transient organ failure (lasting less than 48 hours) and is often associated with local or systemic complications. Early mortality is low, but secondary infection of necrotic tissue increases the risk of mortality in later stages.

Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP)

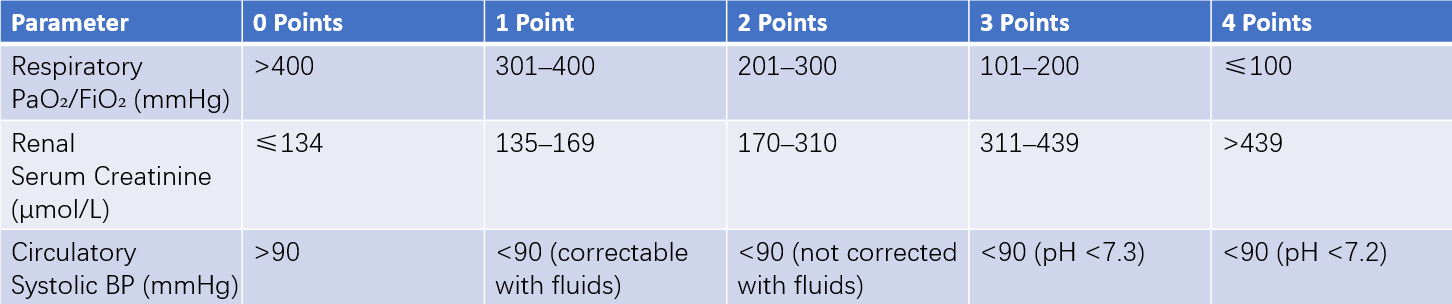

Found in about 10% of cases, SAP is characterized by persistent organ failure (lasting more than 48 hours) that does not resolve spontaneously. Commonly affected systems include respiratory, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Organ failure is typically assessed using the modified Marshall score, with a score of ≥2 indicating organ failure. Most SAP cases involve hemorrhagic necrotizing pancreatitis. Symptoms include extensive peritonitis, significant abdominal distension, and absent or reduced bowel sounds. Ecchymoses in the flanks or around the umbilicus (Grey-Turner's sign or Cullen's sign, respectively) are occasionally observed. Severe cases may progress to shock, multiple organ dysfunction, and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

Table 1 Modified Marshall scoring system

###Clinical Staging

Acute pancreatitis is divided into two stages, early and late, based on the two peaks of mortality, although these stages may overlap.

Early Stage

Occurs within the first week of onset and may extend to the second week. The main pathophysiological change is a systemic inflammatory cascade triggered by abnormal pancreatic enzyme activation. This stage is clinically manifested by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and may lead to multiple organ dysfunction. During this stage, local pancreatic morphological changes do not reliably reflect disease severity.

Late Stage

Commences one week after onset, with the illness lasting weeks to months. This stage is observed in MSAP or SAP cases. Clinical manifestations include persistent SIRS, organ dysfunction, or organ failure.

Complications

Local Complications

These include:

- Acute peripancreatic fluid collection.

- Pancreatic pseudocyst.

- Acute necrotic collection.

- Walled-off necrosis.

Each of these complications can be either infectious or sterile. Among these, infectious necrosis refers to secondary infection in cases 3 and 4.

Other complications include pleural effusion, gastric outlet obstruction, gastrointestinal fistulas, abdominal or gastrointestinal bleeding, and splenic or portal vein thrombosis.

Systemic Complications

Systemic complications include SIRS, sepsis, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and abdominal compartment syndrome.

Treatment

The treatment approach for acute pancreatitis is based on its grading, staging, and etiology.

Non-Surgical Management

Non-surgical treatment is suitable for mild acute pancreatitis, as well as for moderate-to-severe and severe acute pancreatitis without clear indications for surgical intervention. Severe cases often require admission to the ICU for management of critical illness and organ function support, including mechanical ventilation and bedside dialysis if necessary.

Fasting and Gastrointestinal Decompression

Continuous gastrointestinal decompression reduces vomiting, alleviates abdominal distension, and lowers intra-abdominal pressure.

Fluid Resuscitation and Shock Management

Intravenous fluid administration replenishes electrolytes, corrects acidosis, prevents and treats hypotension, stabilizes circulation, and improves microcirculation.

Antispasmodic and Analgesic Therapy

Antispasmodic and analgesic medications such as anisodamine or atropine are administered after a definitive diagnosis. If ineffective, mild opioids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be used. Although morphine may increase Oddi sphincter tension, it has no adverse effect on prognosis.

Inhibition of Pancreatic Secretion

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 receptor antagonists can indirectly inhibit pancreatic secretion. Somatostatin is also effective in suppressing pancreatic secretions.

Nutritional Support

During the fasting period, total parenteral nutrition serves as the primary source of nourishment. Once the condition stabilizes and intestinal function recovers, enteral nutrition can be initiated early, followed by a gradual return to oral feeding.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are indicated for evidence of infection. Common pathogens include Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Surgical Management

Indications

Indications for surgery include:

- Inability to exclude other acute abdominal conditions.

- Presence of distal common bile duct obstruction or biliary infection.

- Complications such as intestinal perforation, significant hemorrhage, or pancreatic pseudocyst.

- Pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis with infection.

Surgical Procedures

The primary surgical approach involves necrosectomy and drainage. This can be performed through open surgery (via abdominal or retroperitoneal incisions) or minimally invasive methods such as laparoscopic or endoscopic techniques (e.g., gastrointestinal endoscopy or nephroscopy) for necrosectomy and drainage.

Open surgery involves a transverse or midline upper abdominal incision, combined with lateral retroperitoneal incisions if necessary, to access the omental bursa and paracolic gutters for removal of peripancreatic and retroperitoneal fluid, pus, and necrotic tissue. After thorough irrigation, multiple drainage tubes are placed to facilitate postoperative irrigation and drainage.

For extensive necrosis or active bleeding, the incision may remain open and packed to allow repeated debridement or timely re-exploration for hemostasis.

Adjunctive procedures, such as jejunostomy for enteral nutrition or biliary drainage, are also performed when necessary.

Retroperitoneal approaches require preoperative imaging for localization. A lateral retroperitoneal incision through the flank allows access for removal of necrosis and drainage.

For secondary intestinal fistulas, the fistulous opening can be exteriorized or a proximal stoma created.

Surgical Treatment of Biliary Pancreatitis

The primary objective is to alleviate biliary obstruction and ensure effective bile drainage. Management depends on the presence of gallbladder and/or bile duct stones.

For gallbladder stones causing mild symptoms, cholecystectomy may be performed during the initial hospitalization. For severe conditions, surgery is delayed until the patient stabilizes, and elective cholecystectomy is planned.

In the presence of bile duct stones with biliary obstruction, endoscopic sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and nasobiliary drainage should be performed on an urgent or early basis.