Etiology and Pathology

Extrahepatic bile duct stones are categorized into primary and secondary stones. Primary stones are often brown pigment stones, formed due to factors such as biliary infections, bile duct strictures, segmental biliary dilations, or foreign bodies in the bile ducts (e.g., remnants of parasites like Ascaris, Clonorchis sinensis, or surgical suture materials). Secondary stones primarily originate from gallbladder stones that migrate into the bile duct and remain there, making them mostly cholesterol or pigment stones. A small proportion of cases involve stones originating from intrahepatic bile ducts.

Stones within the bile ducts primarily lead to the following complications:

Acute and Chronic Cholangitis

Stones cause bile stasis, making the area prone to infections. Infections result in mucosal congestion and edema of the bile duct walls, worsening the obstruction. Repeated bouts of cholangitis lead to fibrosis and thickening of the bile duct walls, narrowing the ducts and causing upstream bile duct dilation.

Systemic Infection

Bile duct obstruction increases intrabiliary pressure, allowing infected bile to flow retrograde through the bile canaliculi into systemic circulation, which can result in sepsis.

Liver Damage

Obstruction accompanied by infection can lead to liver cell damage, and in severe cases, hepatocyte necrosis or the formation of a pyogenic liver abscess. Chronic infections and liver damage may result in biliary cirrhosis.

Biliary Pancreatitis

Stones impacted at the ampulla of Vater can induce acute and/or chronic pancreatic inflammation.

Clinical Manifestations

Most individuals are asymptomatic or experience only mild epigastric discomfort. When stones cause bile duct obstruction, recurrent abdominal pain or jaundice may occur. Secondary cholangitis can present with the classic Charcot's triad of abdominal pain, fever with chills, and jaundice.

Abdominal Pain

Pain is localized to the epigastrium or right upper quadrant, often presenting as colicky and intermittent or as constant pain with intermittent exacerbations. It may radiate to the right shoulder or back and is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Pain is caused by stones migrating downward and lodging at the distal common bile duct or the ampulla of Vater, inducing spasm of the smooth muscle in the biliary tract or the sphincter of Oddi. If the stone floats upward due to bile duct dilation or smooth muscle relaxation, the impaction may relieve, and the abdominal symptoms often subside.

Fever with Chills

Secondary infections due to bile duct obstruction lead to cholangitis. Inflammation and edema of the bile duct walls exacerbate the obstruction, increasing intrabiliary pressure. Bacteria and toxins may retrograde into the bloodstream through the bile canaliculi, resulting in systemic infection. Approximately two-thirds of patients experience fevers with chills, typically presenting as intermittent fever, with body temperatures ranging from 39°C to 40°C.

Jaundice

Jaundice may develop due to bile duct obstruction. The severity, onset, and duration of jaundice depend on the degree, location, and presence of accompanying infection. Partial bile duct obstruction results in mild jaundice, whereas complete obstruction causes more pronounced jaundice. Stones lodged at the sphincter of Oddi often lead to complete obstruction with progressive deepening of jaundice.

In cases of cholangitis, edema surrounding stones can narrow or completely close gaps in the bile duct mucosa, worsening jaundice. Jaundice may fluctuate or appear intermittently depending on the progression and resolution of inflammation. Accompanying symptoms may include darkened urine, light-colored stools, or clay-colored stools in cases of complete obstruction, along with pruritus.

Physical Examination

Between episodes, no significant findings may be present, or mild tenderness might be observed in the epigastrium or right upper quadrant. During cholangitis episodes, varying degrees of peritoneal signs may be observed, predominantly in the right upper quadrant. In cases of extensive exudation or perforation, diffuse peritonitis signs may appear. Occasionally, the gallbladder may be palpable and tender.

Auxiliary Examinations

Laboratory Tests

Elevated serum total and conjugated bilirubin levels, increased transaminases, and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels are common findings. Urine bilirubin increases, while urobilinogen in urine decreases or disappears, and fecal urobilinogen levels may also decrease. Peripheral leukocyte and neutrophil counts typically rise during cholangitis episodes.

Imaging Studies

X-ray

Non-calcium-containing stones will not be visible, though calcium-containing stones may appear on plain abdominal X-rays.

Ultrasonography

This is the preferred method for diagnosing stones, as it identifies their size and location. Biliary dilation in the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts may be visible in obstructive cases. However, distal choledocholithiasis may not be clearly visualized due to interference from obesity or bowel gas.

Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)

EUS is less affected by obesity or bowel gas and is valuable for diagnosing stones in the distal common bile duct.

PTC and ERCP

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are invasive techniques that can clearly identify stones and their locations. However, these methods carry risks such as inducing cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, bleeding, bile leakage, or other complications. ERCP sometimes requires sphincterotomy (EST), which may impair the function of the sphincter of Oddi.

CT Scan

CT imaging can detect bile duct dilation and the location of stones, but calcium-free stones may be less visible due to the appearance of bile ducts as negative spaces on CT images.

MRCP

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is noninvasive and can pinpoint the site of bile duct obstruction. Although it may not reliably detect stones, it is helpful for identifying site-specific obstructions in the bile duct, aiding the diagnostic process.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically straightforward based on clinical presentation and imaging studies. Differentiating abdominal pain from the following conditions may be necessary:

Right Renal Colic

The pain originates in the right flank or lower back and radiates to the right inner thigh or external genitalia. Hematuria (gross or microscopic) is typically present, without fever. The abdomen remains soft, with no peritoneal irritation signs, but right renal percussion tenderness or periumbilical ureteral pressure tenderness may be observed. Abdominal X-rays may reveal stones in the kidney or ureter regions.

Intestinal Colic

Pain is concentrated around the periumbilical area. In cases of mechanical bowel obstruction, associated symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, and the absence of flatus and bowel movements. Bowel loops may be visibly distended, bowel sounds hyperactive, and gurgling sounds or "water splash" noises may sometimes be heard. Abdominal tenderness and/or peritoneal signs may vary in degree and extent. Abdominal X-rays often show intestinal distension and air-fluid levels.

Ampullary Carcinoma or Pancreatic Head Cancer

In cases presenting with jaundice, differentiation is required. These conditions typically have a slow onset, with progressive deepening of jaundice. Abdominal pain is either absent or mild and may be limited to vague upper abdominal discomfort, generally without chills and high fever. During physical examination, the abdomen is soft, with no peritoneal irritation signs. The liver is enlarged, and a distended gallbladder may often be palpated. Advanced cases may present with ascites or cachexia. ERCP, MRCP, and CT imaging can aid diagnosis, and EUS provides additional value for differential diagnosis.

Treatment

Surgical treatment remains the primary approach for managing extrahepatic bile duct stones. Surgical goals include complete stone removal, relief of bile duct obstruction, and maintenance of biliary drainage postoperatively. For single or few stones (2–3) with a diameter smaller than 10 mm, endoscopic stone removal via duodenoscopy can be effective, provided the indications are strictly adhered to; however, debates persist regarding the merits of performing endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) during stone extraction.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Non-surgical management may be employed as preoperative preparation. Key measures include:

- Antibiotic Therapy: Antibiotics should be selected based on sensitivity testing. Empirical treatment may involve antibiotics with high bile concentrations targeting Gram-negative bacteria.

- Antispasmodic Therapy.

- Choleretic Therapy: This may involve herbal compounds.

- Correction of Electrolyte and Acid-Base Imbalances.

- Nutritional Support: This includes supplementation with vitamins and, if necessary, parenteral nutrition for fasting patients.

- Liver Protection and Correction of Coagulation Abnormalities.

Elective surgery is preferred after controlling biliary tract infections.

Surgical Treatment

Common surgical methods include:

Common Bile Duct Exploration with T-Tube Drainage

This procedure can be performed via laparoscopy or open surgery. It is suitable for isolated common bile duct stones if there is no upstream or downstream ductal stricture or other abnormalities. Patients with concurrent gallbladder stones and cholecystitis may undergo cholecystectomy during the same operation. Intraoperative cholangioscopy, cholangiography, or ultrasonography is recommended to minimize residual stones.

Postoperative management involves monitoring and maintaining the functionality of T-tube drainage:

The volume and nature of bile drainage must be monitored. Daily bile output is typically around 200–300 mL, which should be clear in appearance. If the T-tube fails to drain bile, potential issues such as dislodgment or kinking of the T-tube need to be investigated. Excessive bile output warrants evaluation for distal bile duct obstruction. Cloudy bile should be assessed for possible residual stones or unresolved infection.

Postoperative T-tube cholangiography is generally performed 10–14 days after surgery, with continued drainage for at least 24 hours thereafter, followed by trial closure of the T-tube. If patients remain asymptomatic, the T-tube may remain closed.

In cases where bile ducts are patent and free of stones or other abnormalities, T-tubes placed during open surgery are typically removed after approximately 4 weeks. For laparoscopic cases, the removal schedule may be extended slightly.

If residual stones are detected through cholangiography, approximately 4–8 weeks postoperatively, after fibrotic tract formation around the T-tube, cholangioscopy and stone retrieval may be performed.

Biliary-Enteric Diversion

Also known as biliary-enteric drainage, this procedure is indicated for:

- Inflammatory strictures in the distal common bile duct causing unrelievable obstruction, accompanied by bile duct dilation.

- Anomalies in the biliopancreatic duct junction, where pancreatic secretions directly enter the bile duct.

- Cases requiring partial bile duct resection where direct duct-to-duct anastomosis is not feasible.

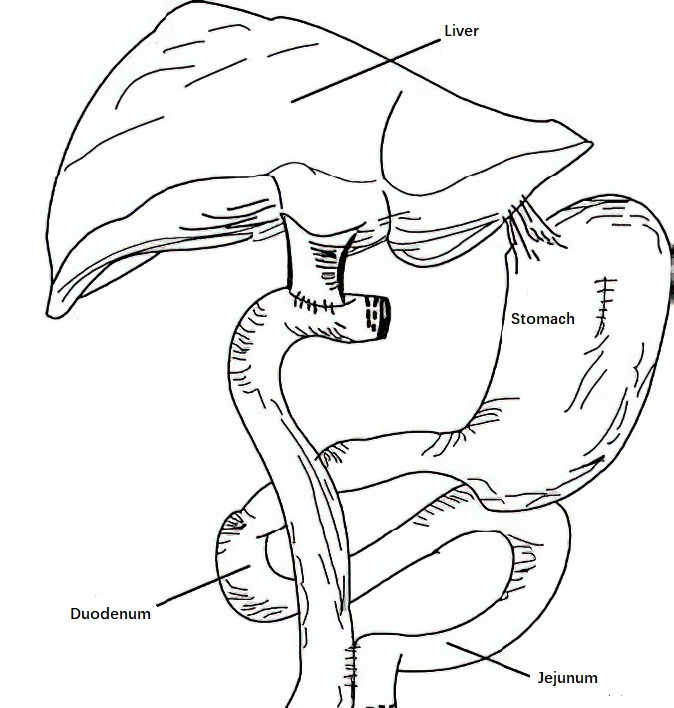

The most commonly used approach is a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. To prevent retrograde infection, the length of the intestinal limb in the Y-anastomosis should exceed 40 cm.

Figure 1 Diagram of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy

Key considerations for biliary-enteric diversion include:

- Loss of gallbladder function, necessitating concurrent cholecystectomy.

- The anastomosis lacks sphincter-like functionality akin to the sphincter of Oddi, so surgical indications must be strictly adhered to.

- Impacted stones at the opening of the common bile duct may be removed through endoscopic or surgical sphincterotomy if stone extraction is otherwise not possible.