Gallbladder stones (cholecystolithiasis) are primarily composed of cholesterol stones, mixed stones predominantly containing cholesterol, or black pigment stones. The condition is common in adults, with its prevalence increasing with age, particularly after 40 years. It is more frequently observed in women.

The formation of gallbladder stones is influenced by multiple factors. Any condition that alters the ratio of cholesterol to bile acids and phospholipids or causes bile stasis can contribute to their formation. Examples include female hormones, obesity, pregnancy, high-fat diets, prolonged parenteral nutrition, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, gastric resection or gastrointestinal anastomosis, ileal diseases, post-ileal resection, cirrhosis, and hemolytic anemia.

Clinical Presentation

The majority of patients are asymptomatic, referred to as silent gallstones. With the increasing availability of health screenings, the detection of asymptomatic gallstones has risen significantly. Typical symptoms include biliary colic, which occurs in only a small proportion of patients, while other common presentations involve acute or chronic cholecystitis. The primary clinical manifestations are as follows:

Biliary Colic

The classical presentation often occurs after a large meal, consumption of fatty foods, or positional changes during sleep. These factors can trigger gallbladder contraction or stone migration, combined with vagal nerve stimulation. Stones may become impacted in the infundibulum or neck of the gallbladder, leading to obstruction of gallbladder emptying and increased intraluminal pressure, which induces severe colicky pain. The pain is located in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium, either intermittent or constant with intermittent exacerbations. It may radiate to the right scapular region or back. In some cases, the intensity of the pain prevents patients from accurately localizing it. Symptoms such as nausea and vomiting may accompany the pain. About 70% of patients experience recurrent episodes of biliary colic within a year of the first attack, with attacks becoming more frequent over time.

Epigastric Discomfort

Many patients experience vague pain or discomfort in the epigastrium or right upper quadrant, particularly after overeating, consuming fatty foods, or during stressful periods or inadequate rest. Symptoms such as bloating, belching, or hiccups are common and may lead to a misdiagnosis of "gastric disease."

Hydrops of the Gallbladder

Prolonged impaction or obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones without secondary infection can result in hydrops of the gallbladder. The gallbladder mucosa absorbs bile pigments from bile and secretes mucinous material, leading to the accumulation of clear, colorless fluid, often referred to as "white bile."

Other Associated Complications

Jaundice is rare and usually mild when present.

Small stones passing through the cystic duct may enter the common bile duct, leading to the formation of common bile duct stones.

Stones entering the common bile duct and passing through the sphincter of Oddi may cause injury or become impacted at the ampulla, leading to pancreatitis, termed biliary pancreatitis.

Chronic inflammation or perforation caused by stones compressing the gallbladder may result in a cholecystoenteric fistula, such as a cholecystoduodenal or cholecysto-colonic fistula. Large stones passing through such fistulas into the intestines can occasionally cause gallstone ileus.

Long-term irritation from stones and inflammation may increase the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Mirizzi Syndrome

This rare condition occurs due to specific anatomical factors, such as an excessively long parallel course of the cystic duct and the common hepatic duct or a low confluence of these ducts. Gallstones that become impacted in the neck of the gallbladder or larger stones in the cystic duct can compress the common hepatic duct, leading to its narrowing. This condition is associated with recurrent episodes of cholecystitis and cholangitis. Chronic inflammation may eventually lead to cholecystohepatic duct fistulas, disappearance of the cystic duct, and stones partially or completely obstructing the common hepatic duct. Clinically, patients present with recurrent episodes of cholecystitis, cholangitis, and jaundice. Imaging studies reveal an enlarged gallbladder, dilation of the common hepatic duct, while the common bile duct appears normal.

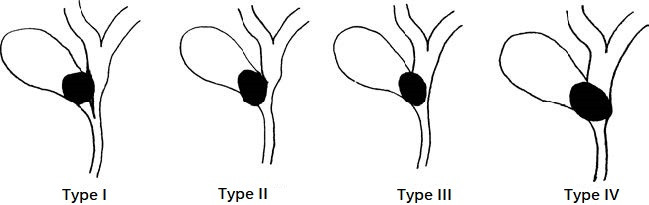

Figure 1 Mirizzi syndrome

Csendes classification:

Type I: External compression leads to partial or complete obstruction of the common bile duct, but no fistula formation is present.

Type II: Cholecystocholedochal fistula involving less than one-third of the duct circumference.

Type III: Cholecystocholedochal fistula involving more than one-third but less than two-thirds of the duct circumference.

Type IV: Cholecystocholedochal fistula involving more than two-thirds of the duct circumference.

Diagnosis

A history of typical biliary colic serves as an important basis for diagnosis. Imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasound is the preferred method due to its near 100% diagnostic accuracy. Diagnostic ultrasound reveals hyperechoic foci within the gallbladder that move with positional changes and are followed by acoustic shadowing, which confirms the presence of gallbladder stones.

In approximately 10%–15% of cases, the stones contain more than 10% calcium and may be visible on an abdominal X-ray. However, differentiation from renal stones in the right kidney is required. CT and MRI can also detect gallbladder stones but are not routinely performed.

Treatment

Cholecystectomy is the preferred treatment for symptomatic and/or complicated gallbladder stones. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is typically performed as the standard procedure due to its advantages, including faster recovery, minimal trauma, less pain, and smaller scars. For complex cases or in facilities without laparoscopic equipment, open cholecystectomy is also an option.

Prophylactic cholecystectomy is generally not recommended for children with gallbladder stones or asymptomatic adults with gallbladder stones. Observation and follow-up are usually sufficient. Long-term studies indicate that approximately 30% of patients eventually develop symptoms or complications, necessitating surgery. Therefore, surgical treatment may need to be considered under the following circumstances:

- A large number of stones, or stone diameters ≥2–3 cm.

- Calcification of the gallbladder wall or porcelain gallbladder.

- Gallbladder polyps with a diameter ≥1 cm.

- Thickening of the gallbladder wall (>3 mm), indicating chronic cholecystitis.

During cholecystectomy, certain situations warrant simultaneous exploration of the common bile duct:

- Preoperative history, clinical presentation, or imaging suggest obstruction of the common bile duct, including obstructive jaundice, common bile duct stones, recurrent biliary colic, cholangitis, or pancreatitis.

- Intraoperative findings confirm abnormalities in the common bile duct, such as intraoperative cholangiography identifying stones, worms, or masses in the common bile duct, or the palpation of such abnormalities.

- Common bile duct dilation with a diameter exceeding 1 cm, markedly thickened bile duct walls, the presence of pancreatitis or pancreatic head masses, purulent or bloody bile, or sandy bile pigments found during bile duct aspiration.

- Small gallbladder stones with the potential to migrate into the common bile duct.

Intraoperative cholangiography or choledochoscopy is advised when feasible to improve diagnostic accuracy and to minimize the risks of unnecessary complications. Blind probing using metal instruments should be avoided. After common bile duct exploration, placement of a T-tube for drainage is typically required.