Congenital biliary dilatation refers to abnormal dilation that can occur in any part of the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts. Since it frequently involves the common bile duct, it was previously called congenital cystic dilatation of the common bile duct. Currently, it is collectively termed biliary dilatation. The male-to-female ratio for this condition is approximately 1:3–4, with about 80% of cases manifesting during childhood.

Etiology

Congenital biliary dilatation arises from congenital dysplasia of the bile duct wall and stenosis or atresia of the distal bile duct, which are fundamental contributing factors. Possible causes include:

- Congenital anomaly of pancreatobiliary junction.

- Congenital bile duct dysplasia.

- Genetic factors.

Classification

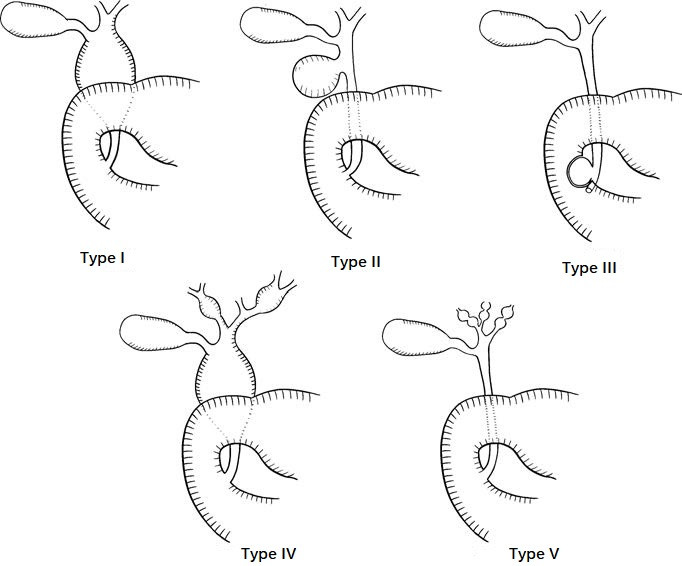

Based on the location, extent, and morphology of the dilated bile ducts, the condition is divided into five types:

- Type I: Cystic dilatation. This is the most common type, involving either the entire or partial sections of the common hepatic and common bile ducts. The bile duct is dilated into a spherical or flask-like shape, while the distal bile duct is severely stenosed. The cystic duct typically joins the cystic dilatation, while the left, right hepatic ducts, and intrahepatic bile ducts remain normal.

- Type II: Diverticular dilatation. This rare form involves a localized, diverticulum-like expansion of the lateral wall of the common bile duct.

- Type III: Cystic protrusion at the duodenal opening of the common bile duct. The distal common bile duct near its duodenal opening is cystically dilated, with the dilation protruding into the duodenal lumen, leading to partial biliary obstruction.

- Type IV: Combination of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation. The intrahepatic bile ducts show multiple cystic dilatations of varying sizes, while the extrahepatic bile ducts also exhibit cystic enlargement.

- Type V: Intrahepatic bile duct dilatation (Caroli disease). This involves multiple cystic dilatations of the intrahepatic bile ducts accompanied by hepatic fibrosis, with no extrahepatic bile duct dilation.

Figure 1 Classification of congenital biliary dilatation

The wall of the dilated bile duct may develop ulcers due to inflammation and bile stasis, which can, in some cases, lead to malignancy. Stones may also form inside the cystic dilated bile duct, with the incidence of choledocholithiasis in adults reaching as high as 50%.

Clinical Presentation

The classic clinical presentation includes the triad of abdominal pain, an abdominal mass, and jaundice.

Abdominal Pain

Pain is typically located in the upper right abdomen and manifests as persistent dull pain.

Jaundice

Jaundice is intermittent.

Abdominal Mass

Over 80% of patients have a palpable, smooth, cystic mass in the upper right abdomen.

If the condition is complicated by infection, symptoms may include deepening jaundice, worsening abdominal pain, tenderness over the mass, chills, and fever. Late-stage manifestations may include symptoms of biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Some patients may show elevated blood and urinary amylase levels.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is straightforward in cases with the classic triad or recurrent episodes of cholangitis. However, only 20%–30% of patients simultaneously exhibit all three symptoms; most patients present with only one or two, necessitating further examinations for confirmation.

Ultrasound, CT, or MRCP can diagnose the majority of congenital biliary dilatation cases.

PTC and ERCP can assist in the diagnosis of more challenging cases.

Treatment

Congenital biliary dilatation can cause serious complications such as recurrent cholangitis, cirrhosis, malignancy, or rupture of the cystically dilated bile duct. Once diagnosed, surgical intervention is recommended promptly.

Surgical Options

The primary approach involves resection of the dilated bile duct and a Roux-en-Y biliodigestive anastomosis.

If complete resection of the dilated bile duct is not feasible, mucosal stripping and partial excision are considered.

For patients with severe infections or perforation, bile drainage surgery may first be performed. Once symptoms are controlled, jaundice subsides, and general health improves, a second-stage surgery may follow.

Cases involving localized intrahepatic bile duct dilatation may require partial hepatectomy.

For diffuse intrahepatic bile duct involvement or cirrhosis, liver transplantation may be considered.