Biliary atresia is the most common cause of persistent jaundice in neonates. The condition can affect the entire biliary tract, but extrahepatic biliary atresia is more commonly observed, accounting for 85%–90% of cases.

Etiology

Biliary atresia is a progressive sclerosing disease of the bile ducts. Many infants are able to excrete bile at birth but subsequently develop biliary atresia. The etiology includes several hypotheses:

The congenital malformation hypothesis suggests that biliary atresia occurs when bile ducts fail to undergo vacuolization or undergo incomplete vacuolization during the embryonic stage of 2–3 months, resulting in partial or complete obstruction.

Biliary atresia may be associated with chromosome abnormalities, often accompanied by congenital anomalies, such as absence of the inferior vena cava, portal vein malposition, splenic abnormalities, or situs inversus.

Many researchers believe that perinatal viral infections lead to inflammatory responses, which play a significant role in the development of biliary atresia.

Other theories suggest that autoimmune processes or bile duct ischemia are contributing factors. Additionally, biliary atresia and sclerosing cholangitis have been found to share similar pathological processes.

Pathology

The majority of biliary duct developmental abnormalities result in biliary atresia, with only a small number showing stenosis. If bile duct obstruction is not promptly relieved, it can progress to biliary cirrhosis, which is an irreversible condition in later stages.

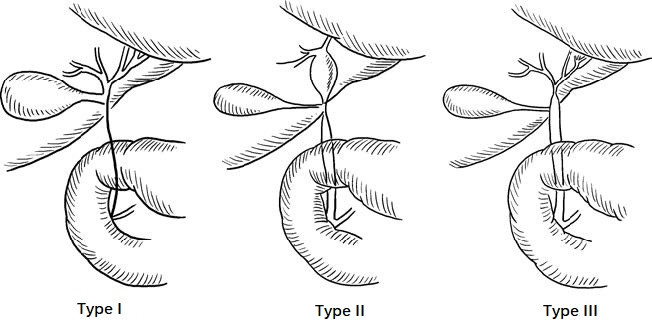

Extrahepatic biliary atresia is classified into three main types:

- Type I: Involves only the common bile duct.

- Type II: Involves atresia of the hepatic ducts.

- Type III: Involves atresia of the bile ducts near the hepatic hilum.

Figure 1 Biliary atresia

Type III is the most common.

Clinical Presentation

Jaundice

Obstructive jaundice is the most prominent symptom. Physiologic jaundice, which should resolve after 1–2 weeks of birth, becomes more pronounced and progressively worsens. The sclera and skin turn from golden-yellow to greenish-brown or dark green. Stool becomes clay-colored, and urine darkens to a tea-like color. The skin may exhibit excoriation marks due to itching.

Poor Nutrition and Developmental Delay

While the condition appears mild initially, with normal nutritional status and growth, symptoms progressively worsen. By 3–4 months of age, malnutrition, anemia, developmental delay, and lethargy often develop. In severe cases, neuropsychiatric symptoms like somnolence, irritability, or hepatic encephalopathy may occur.

Hepatosplenomegaly

At birth, the liver size is generally normal, but it progressively enlarges as the disease advances. By 2–3 months, biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension develop, presenting with splenomegaly, bleeding tendencies, and coagulation dysfunction. Complications such as infections, bleeding, and liver failure can arise, and in severe cases, the condition may result in death.

Diagnosis

Infants presenting with persistent jaundice, clay-colored stools, dark tea-colored urine, and hepatomegaly within 1–2 months of age should raise suspicion for biliary atresia. The following findings support the diagnosis:

- Persistent progression of jaundice beyond 3–4 weeks of age, unresponsive to cholagogues, phenobarbital, or corticosteroid treatments, along with elevated direct bilirubin levels.

- Absence of bile in duodenal drainage fluid.

- Ultrasound findings of underdeveloped or absent extrahepatic bile ducts and gallbladder.

- Lack of radionuclide tracer excretion into the intestines on 99mTc-EHIDA scans.

- ERCP or MRCP evidence revealing biliary atresia.

- Liver biopsy aiding in diagnosis if uncertainty remains.

Differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish biliary atresia from conditions like neonatal hepatitis, congenital metabolic disorders, hemolytic diseases, or transient jaundice due to bile concentration or impaired excretion caused by medications (e.g., vitamin K) or severe dehydration. These conditions tend to resolve after 1–2 months of anti-infective, cholagogue, or corticosteroid treatment. Ultrasound, MRCP, or ERCP can provide valuable assistance in distinguishing biliary atresia from such conditions.

Treatment

Surgery is the only effective treatment and is best performed within 2 months of birth, before irreversible liver damage occurs. Delayed surgery results in poor prognosis due to established biliary cirrhosis.

Surgical Approaches

If part of the extrahepatic bile ducts remains patent and the gallbladder is normal in size, a Roux-en-Y anastomosis between the gallbladder or extrahepatic bile ducts and the jejunum may be performed.

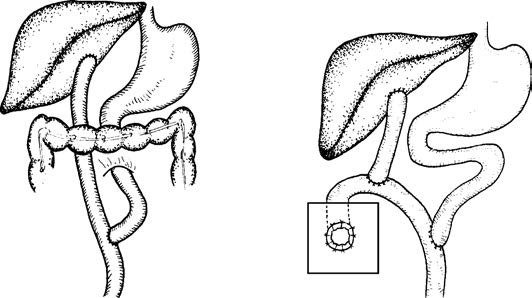

For bile duct atresia involving the hepatic hilum but with remaining intrahepatic bile ducts, a Kasai portoenterostomy is performed. This involves creating a transverse incision in the hepatoduodenal ligament, isolating non-vascular fibrous structures at the hepatic hilum, and anastomosing the jejunum to the bile-secreting fibrous tissue using a Roux-en-Y configuration. To prevent postoperative biliary complications and monitor bile drainage, a jejunal loop stoma can be created on the abdominal wall.

Figure 2 Schematic representation of Kasai surgery for biliary atresia

Liver transplantation is indicated for cases with complete intra- and extrahepatic bile duct atresia, established cirrhosis, or failure of the Kasai procedure.

Preoperative Preparation

The focus is on improving liver function and nutritional status, controlling infections, and correcting bleeding tendencies. Preoperative preparation should typically be completed within 3–5 days.